Diadem: Selected Poems

Diadem: Selected Poems

by Marosa di Giorgio

Translated by Adam Giannelli

BOA Editions, Oct 2012

80 pages / $16 Buy from BOA Editions or Amazon

In Diadem, Di Giorgio’s prose-styled poems are a collage of images ranging from the surreal to the innocent and childlike. Shadows stalking about the farm house amongst rose gardens, God appearing as a face and speaking, and children performing plays in the garden. Giorgio speaks to us through these images, playing with them, distorting them, and living in them; she speaks of “The owls, with their dark overcoats, thick spectacles, and strange little bells”, and “Virgin Mary, enormous wing over my whole childhood and the whole countryside.” These images, contrasted with the speech-like prose style, paints surrealistic and beautiful pictures of culture, childhood, sexuality, and death.

“God’s here.

God speaks.”

As noted by the translator of the collection of poems, Adam Giannelli, these poems could be read as a novel, cover to cover, or on their own as individual pieces, and they would still have the same power and depth. The poems themselves blend and blur the lines between each other, in effect recreating an idea of recalling memories of the past; sometimes fantasy, sometimes all too real, and always fleeting and hard to properly pin down.

The poems themselves are often quick to change in subject matter and mood; often these poems begin with something childlike, like a story or a memory.

“We would put on plays in the gardens, at twilight, beside the cedar and carob trees; the show was improvised on the spot, and I was always afraid I wouldn’t know what to say, although that never happened.”

The poems often quickly turn, however, such as in this fragment. What is meant by a play is quickly distorted into something else; be it the anxieties of adolescence, maturation, or something more so. What makes these pieces stand out is that sometimes it is hard to know exactly what is happening, but it doesn’t take anything away from it.

“The mushrooms are born in silence; some are born in silence; others, with a brief shriek, a bit of thunder.”

The flexibility Di Giorgio employs with image, as well as grammatical constraints, helps give the pieces a somewhat corporeal feel; there is some sort of otherness to them.

“Each ones bears-and this is the horrible part-the initials of the dead person from which it springs.”

The themes turn so quickly that the reader almost can’t keep up. First one has this image of a mushroom growing in the ground, but being born of thunder turns the poem; why would there be thunder? And then, the initials of the dead are introduced, so perhaps these are supposed to symbolize some sort of cultural thing; death and rebirth. However, the piece makes another turn in the very next line.

“But in the afternoon the mushroom buyer comes and starts to pick them. My mother lets him. He chooses like an eagle. That one, white as sugar, pink one, grey one.”

Here now the subject has changed again; perhaps the mushroom buyer is reaping the spoils of war? Perhaps this is westernization? Maybe they are just regular mushrooms? It is these parallels of images working together, juxtaposing themselves rapidly and fluidly, which creates powerful pieces of poetry all under a single breath.

“The locusts came from Paraguay; each one seemed sheathed in a soft bone, a husk; a waterfall, a deluge, they came tumbling down from the forests in the sky. Everyone ran out to face them. Papa, my grandparents, the owners of all the houses nearby, the farmhands and hounds, wearing huge masks with trailing bears and little dangling lamps, matador suits, as if they were off to fight a bull; they would run out, dressed that way, to scare off the locusts, they used pots and toys. They placed a straw man in every garden, every seedbed; they defended each and every plant/ They caused such havoc, such racket.’

READ MORE >

Diadem: Selected Poems

Diadem: Selected Poems Our Lady of the Flowers, Echoic

Our Lady of the Flowers, Echoic An Ethic

An Ethic Varamo

Varamo  Cunt Norton

Cunt Norton The Childhood of Jesus

The Childhood of Jesus The &Now Awards Volume 2: The Best Innovative Writing

The &Now Awards Volume 2: The Best Innovative Writing The Kind of Girl

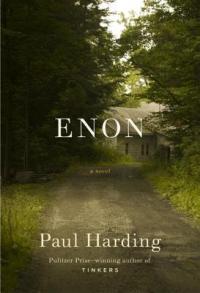

The Kind of Girl Enon

Enon