I am always fascinated by people with whom I disagree, vehemently and sometimes violently, about matters of mutual interest. I have read some of the literary criticism Anis Shivani has written for The Huffington Post and in other venues and regardless of his subject matter, I always have a reaction, usually a reaction that is anything but subdued. Nine times out of ten, I disagree with what Shivani has to say about everything and anything. I suppose that is the mark of a critic who is doing their job effectively–inspiring a reaction, a conversation, a response to their ideas. I am especially curious about what makes Shivani tick because he seems so committed to his opinions on the one hand, and so committed to provocation on the other, though, as you’ll see, he would disagree with that latter statement. I don’t know that you can ever really know how someone thinks or what motivates them but I asked Shivani a few questions about contemporary literature, criticism, the role of the critic, and how he approaches his critical work. He had, as you might imagine, a great deal to say and I disagreed, as you might imagine, with much of what he had to say but as ever, I had a reaction, a response and we had an interesting conversation.

You do a lot as a writer–fiction, poetry, criticism. What is your first love?

Fiction has always been my first love. I write criticism to learn more about fiction. I could also easily have devoted myself to poetry, but although poetry is satisfying in its way, only in fiction does my soul fully engage. There’s no rush like writing fiction, and I can’t do it on autopilot, as it’s possible to do with criticism or even poetry at times. The feeling of euphoria and satisfaction from writing fiction is incomparable. Writing a successful novel is a great challenge, and you have to be a bit of a poet, a bit of a critic, a bit of a dramatist, a bit of a philosopher, a bit of a social scientist, to pull it off. Writing long poems is more exciting than short lyrics, but then one needs a lot of commitment for that. I’m in two minds about having written so many stories early in my career; on the whole perhaps it was a net loss, because I didn’t spend that precious time writing novels. The economics of publishing dictated that I write short stories for many years and get them published in the literary journals, but the story requires a different mindset than a novel and it’s difficult to get the story’s habits out of the mind when one is writing a novel. It teaches compression, which is both a virtue and a fault.

It’s only an unfortunate specialization that limits writers to operating within narrow genres—short stories about a specific region and milieu, for example, or novels dedicated to the same few characters, or lyrical poems relentlessly exploring one’s own ethnicity or geography—otherwise writers in other countries still write in different genres at the same time, and this has always been the case since the beginning of time—until, that is, the academic specialization of literary writing under university patronage in the U.S. in the late twentieth century. I think writers should see themselves as workers in the broad field of the arts—including even Hollywood or popular music, and certainly what used to be called literary journalism in every possible genre. Anything to break the rut, to push the mind toward new challenges so that writing doesn’t fall into preestablished grooves—which is very easy to do, based on the successful formulas in existence. Film is a particularly fruitful cross-fertilizer, as is painting. Really, the arts cannot function in isolation and shouldn’t be practiced and critiqued that way. It’s only unprecedented specialization that has created this unnatural situation, and the writer must be very conscious of that and work hard to break down the false institutional barriers preventing a catholicity, even eccentricity, of interests. The mind desires to switch between different levels of intuition and emotion and logic and these desires should be fed.

What is the responsibility of the critic?

The responsibility of the critic is to use his preferred set of criteria to judge and evaluate whether or not a work of art is good. If it’s not good, he should provide historical context to explain why. One can learn as much, if not more, from so-called negative criticism than from positive criticism. The critic’s responsibility is very moral in this sense. He should be fair to the work or author or national literature in question, not asking more of it than it can reasonably deliver, but he shouldn’t go easy either. The responsibility of the critic is to challenge the reader to not read passively, uncritically, unthinkingly, and to open up for him a whole set of issues that he might not have thought of otherwise. The critic, in my view, is a democrat, in wanting to see different styles of writing flourish, and seeing the good in as many genres as he can possibly keep up with; he shouldn’t be a narrow partisan for a narrow style of writing. It’s the responsibility of the critic to be trained well in his field, just as we expect fiction writers or poets to have mastered their field, so that instead of expressive or spontaneous or on-the-spur emotional reactions, when he critiques he’s as much in conversation with past and present critics as he’s in conversation with the given author’s matrix of influences and connections.

I’m trying to develop a theory of the critic as the literary entrepreneur par excellence—I don’t mean anything as debased and clichéd as a public intellectual, a reactionary idea promoted in defense of a generally acquiescent political culture; I don’t mean the set of promotional and partisan and political commitments implied by the designation “public intellectual.” I mean that the writer of the future should conceive of himself first and foremost as a critic. It’s not that different from how it’s traditionally worked. This would replace the model of the writer learning “craft” by practicing under state or corporate patronage, and instead learning the tradition—assimilating it and arguing with it—at an increasingly deeper level as criticism teaches him to separate the good and the bad in art. I would like to see the critic of the future crossing different cultural fields as a way to broaden his understanding of his own chosen field, and reaching out to mass audiences rather than limiting himself to coterie groups.

In short, I see the renewal of strong criticism as absolutely central to reviving the moribund literary project—and I think we can all agree that it’s in pretty bad shape today, culturally marginal and deservedly so. The responsibility of the critic is to relentlessly ask the question, What is art for? Is there a moral dimension to it? If so, what is it, and does it change, depending on the needs of the society, the state of the world at large, and the particular challenges humanity faces at a given time in overcoming its perennial problems of misery and suffering? The critic is a moralist—yes, it can only be that way.

What does it require to be taken seriously as a critic? Why should you be taken seriously as a critic?

A critic builds a reputation over a long period of time. This doesn’t mean that he can’t have flashes of insight early on in his career. In fact, it’s those early intuitions that often determine his future path, as the rest of his life is spent elaborating and rationally exploring the intuitions that hit him early on without much effort. In my case, in the mid- and late 1990s, it was obvious to me that—not to put too fine a point on it—theory was bullshit, that postmodern preening among secure academics was a lifestyle gesture and pose, not worth taking seriously. I found revolting the whole enterprise of ridiculing “Western” rationality (is rationality Western?) or deploying Derrida’s phallogocentrism and other stolen nonsensical terms, by those who were hyperprivileged beneficiaries of the same phallogocentrism, munificently remunerated, removed from all threats and insecurities at lush ivy-covered campuses, while they decried the benefits—or even the very idea—of science and technology!

My undergraduate education was in economics and at the time, in the early and mid-1990s, I used to think that a faux naïveté toward liberalism (admitting all we know about the tragedies of the twentieth century and yet valuing liberalism’s basic presumptions) was a necessity for poor countries then making the transition to democracy. In the last fifteen to twenty years—since the end of the Cold War consensus—we as a country have regressed tremendously. We’ve become incapable of criticism—that seems to me the fundamental change—and it penetrates politics, culture, social life, even intimate life. We’ve become grossly indulgent and delusional and whiny and increasingly leery of responsibility. So we need to return to the fundamentals of liberal morality, and I’ve forced myself not to get out of touch with reality as I saw the academics of the 1990s doing. Connected with postmodern indulgence was the favoritism shown to multicultural literature, which seemed to me shallow and irresponsible, in the form corporate publishing promoted it and academic culture adopted it. I saw a frightening emptiness to prose narrative, defined by narcissism and lack of global understanding, a willful denial of reality. I may have understood all that at the gut level but it took many years to order these intuitions in a coherent intellectual framework.

So to answer your question the critic, to be taken seriously, must have thought long and hard about the fundamental questions he’s set for himself at the beginning of his career, and proven himself by the increasingly more sophisticated articulation of his views. Of course, he may still be taken seriously, if the insight is blinding and ferocious, at an early age, but then the response will be in the nature of asking those insights to be proven, backed up with logic and reason. I’ve extensively published my developing ideas in criticism—they didn’t just spring up overnight at the Huffington Post—for a decade. Do people in the online world still read the Georgia Review and Michigan Quarterly Review and Antioch Review and Cambridge Quarterly and London Magazine? I’ve published similar criticism as you now see online in the very best literary journals for a long time, but unfortunately reaching only a minimal audience; I’m grateful to have a much wider audience now with the online opportunity, for the same ideas I’ve been publishing in relative obscurity. The quality print journals can be quietly ignored; not these new venues.

How is the role of the professional critic evolving now that certain forms of criticism have become rather democratic, or some might say, anarchic?

Yes, this is the absolute crux of the matter. I would say that thanks to the Internet—which is going to be the crucial public sphere of the future, though it has barely begun to deliver on the promise—criticism is definitely becoming democratic and even anarchic, and that’s wonderful, the greatest development critics can build on. The legitimacy of gatekeepers is crashing, and they were responsible—because of their parochial interests—for taking the passion out of literature. I think the process took off in the early Cold War years, went through different phases, and most recently has manifested itself as a corollary of neoliberal political hegemony; it’s in the interest of elite gatekeepers, like the New Yorker and the New York Times and Poetry, to keep literature at a low boil, to persuade the public that there’s not much going on that’s worthy of passionate debate. Now everyone has a viewpoint and a platform to present it—a review on Amazon, if nothing else. The problem is, as usual new gatekeepers have emerged, so that the solitary voice on a blog read by no one or a review at a site like Amazon doesn’t have quite the same currency as views appearing on the better-read sites. Still, we must believe that if a critic is strong enough, he will eventually gain a wide following; and this is more true than in the old days of print gatekeeping.

It took me a while to come around to the power of the Internet; in the early days I used to think of it as an irredeemable wasteland, but this changed with the rise of blogs in the mid-2000s. Even today, the overwhelming bulk of it is wasteland, although there is some worth even in articulating in public the kinds of thoughts people previously uttered in drunken rages or while feeling suicidal at the proverbial three in the morning. How should the Internet rise to the challenge? How and where will powerful new criticism emerge? As far as literary criticism is concerned, unfortunately the majority of blogs are extensions of the narrow cliques of writing program groupthink. Aside from the more traditional print literary quarterlies, the newfangled ones, the pure product of writing programs, don’t publish any criticism; or if they do, it’s unmitigated praise of fellow writers, a kind of shameless publicity. The major literary blogs are infected by the same cliquishness; they don’t do criticism; they do publicity. But I see this as a transitionary phenomenon.

Ideas about what form criticism should take on the Internet will rapidly evolve until it’s unrecognizable from the present constrained formats. I’ve tried in my work to create all sorts of visual and auditory excitement, but I can see that the potential is still mostly untapped. As the hegemony of current forms of writing dissolves—and the structures are so moribund, it’s bound to happen—democratic criticism on the Internet will become a reality, and real quality, in formats hard for us to imagine at this point, will reach a wider public than ever thought possible. Yes, I’m a raging optimist about the potential of true democracy on the Internet.

A lot of your criticism is quite aggressive and provocative. Why do you take that approach?

It’s “aggressive” only from the point of view of someone writing for one of the tame literary journals or websites; it’s not aggressive from the point of view of the sharpest critics who have plied the trade over the centuries. Most Internet “criticism”—reviews which are really blurbs in flowery language, reverential interviews which never challenge a writer, the sycophancy and nervous politeness and feudal praise—is so far mostly an extension of the genteel, apolitical, personalized mode of thinking engendered in the writing programs. The great critics have been pretty aggressive—it fires me up when I see the New York Times follow a consistent agenda of praising mediocrities and ignoring real literary quality, and shouldn’t it fire you up too? How aggressive should you be when confronted with the literary equivalents of George W. Bush or Sarah Palin? Is any rhetorical tool the limit in countering mediocrity propped up by tottering institutional supports? What deserves my loyalty, art or prestige? Internet criticism, as it exists today, is a form of socialization; a rather elevated form, but that’s what it amounts to.

I’m somewhat surprised by the graduates of writing programs taking up arms in defense of their masters; what did these masters ever do for you and what will they ever do for you? All right, maybe they will come through yet with a recommendation or favor, and maybe you believe they “taught” you certain writing skills, but come on! I’m sorry to have crashed the drunken party, but a couple of years ago, when I started writing online, criticism online was absolutely dead. There was nothing interesting going on, it was all bland and hypocritical and anti-intellectual, and for the most part, it still is.

Provocative—that depends on where you’re coming from. If you’ve never read the great critics of the past—who certainly didn’t shy away from controversy, and deployed every polemical tool at their disposal to sway the reading public to their point of view—and if you’ve only hung around in safe Facebook confines where your friendly doppelganger serves as your own publicity overlord, then of course my criticism will seem aggressive and provocative. You should hear the language I use in my head when I think of the latest literary celebrity cashing in on ignorance. It’s not very pretty language. I actually think I’m quite moderate even in my most “provocative” essays.

The list of 15 overrated contemporary writers you compiled last year has received a great deal of attention. What prompted the writing of that list? Why is compiling such lists a worthwhile exercise? Why are we so enamored with lists designed to calculate greatness or the lack thereof?

It’s absolutely the central role of a critic to define the good and the bad. The idea that one should just leave the bad alone—because time will take care of it, or one should either praise or remain silent—is ludicrous! Understanding the bad helps us understand the good—and in a star-driven culture industry driven by hype and propaganda, this function is all the more important. As for the overrated piece at the Huffington Post, the ideas behind my criticism of Billy Collins, Jorie Graham, Sharon Olds, Jhumpa Lahiri, etc. were developed and published incrementally over many years in the literary journals; if you check out Against the Workshop, you’ll find reviews taking Collins to task, such as when he edited the Best American Poetry, and a substantive essay in the leading British journal of criticism taking apart his whole career (along with Graham, Olds, Glück, and Philip Levine). Collins is a poetry clown, yet he’s the best-selling American poet. I haven’t heard any complaints about the New York Times compiling end-of-the-year best books lists; and yet that’s pure puffery, based on the power and heft of the major trade houses, nothing more than that.

We all have internal ranking systems, and while list-making can sometimes be silly, if it’s backed up by serious thought it can be a very useful exercise to get readers thinking about why the instruments of propaganda—among which I include all the major literary awards in this country—are trying so hard to get us to like certain authors. In the Huffington Post piece, I wanted to get out some core opinions about popular authors in an entertaining fashion. Different personas are in order when approaching different audiences, and judging by the ensuing worldwide clamor, that particular style was a hit. I might just return to that supremely bitchy tone for an encore later this year! Critics can’t be dour and pedantic all the time, they have to learn to approach different audiences at different levels, and in fact create new audiences for the standard stuff of criticism.

In your “New Rules for Writers” essay on Huffington Post, your first rule is for writers to disobey the system. I’m all for working against systems but you attended Harvard and publish in some of the very publications that rise out of the “system.” There seems to be a tension there between what you advise and where you write. Do you perceive that same tension? How can you advise writers to avoid the system when you seem to be deeply entrenched in the system yourself?

This is a particularly bizarre question, which seems to come up again and again, in blogs and in comment threads. And it seems to follow from a real misunderstanding about what I mean by the system and corruption within it. If I publish in the Threepenny Review or Iowa Review, or my books of fiction or criticism are published by reputable independent or university presses, am I disqualified from criticizing the system? In order to point out its corruptions, must I be unpublished, unknown, and uneducated? There’s a difference between honest plying of the field and outright manipulation and corruption. The system works to the advantage of certain authors and to the distinct disadvantage of others. It’s a definite liability not to have been part of the MFA system, whereas even ten or fifteen years ago this wasn’t as true.

I started off with no connections in the literary world, none whatsoever, and built my credibility based on my writing alone. I submitted to patient editors like Dan Latimer at Southern Humanities Review or Laurence Goldstein at Michigan Quarterly Review or Robert Fogarty at Antioch Review or Stephen Corey at Georgia Review or Wendy Lesser at Threepenny Review or John Matthias at Notre Dame Review for years and years before they started taking my work. This is how I learned my trade, and I had zero institutional credibility to back me up. They didn’t know me from Adam (or Adam Haslett), I was never legitimized by the workshop system, and I never got a fellowship from Yaddo or MacDowell—and I never will either, no matter how good my writing gets, because I don’t have the institutional connections; heck, I wouldn’t be able to get a library carrel as an independent scholar, no matter how good my writing, because that’s just not how the system works.

Although I was lucky to have the book accepted almost immediately upon first submission, Anatolia and Other Stories would probably have gone over the heads of ninety-nine percent of small press editors (we won’t even talk about the major houses), had it not been for a brilliant editor, Colleen Ryor (unfortunately no longer with Black Lawrence Press), who picked the manuscript; I consider her something of an outsider too. I don’t doubt that this entirely atypical book would have caused anything but nervousness among the vast majority of small press publishers who like to imagine themselves as mavericks and talent-spotters. That’s been the pattern with all my books, and that’s generally also true of my journal publications. And whatever good things happen to me in the future will probably be as a result of intuitive association with publishers and editors in sync with my nonconformist tendencies.

After college, I decided to go it alone and do whatever was necessary to make time for independent learning (I didn’t “buy” two years of time by paying $100,000 to an MFA program—no one owns my time, I don’t have to buy it back from someone), which involved unimaginable sacrifice and persistence. For about ten years I lived in abject poverty and did nothing but read—I wrote too, but I didn’t just start submitting, I was more interested in filling the huge gaps in my learning. Looking back at it, the intentional hurdles against not having an MFA or being part of the system are so great that it’s absolutely foolhardy to attempt it. Everything I’m doing now is in collaboration with people who are at odds with the system in some way or another and want to see a better situation for books.

Compare this with the experience of the callow, inexperienced, unworldly writer who milks the system for all it’s worth; some good-looking guy or gal in their mid- to late twenties goes straight from Yale to the Writers’ Workshop to the Fine Arts Work Center to the Stegner fellowship, with stints at Yaddo and MacDowell in between, and very thin to non-existent (often just cranky online) publications to back it all up—all because the network functions purely on connections, a very corrupt, almost medieval exclusion. The writing world today is the antithesis of meritocracy. I imagined more than fifteen years ago that meritocracy would be more prevalent in the literary world compared to academia, but the situation is a thousand times worse than in scholarship. Oh, and by the way, I was a fucking rebel at Harvard too—you should ask some of the people who knew me then. The best minds of my generation fucked themselves up on Wall Street—or deconstructing literature for the always already privileged.

Some of your harshest criticism is directed toward MFA programs. I don’t have an MFA but there is ample evidence that MFA programs work quite well and produce good and often great writers. I certainly don’t believe an MFA is necessary to become a writer, but I don’t begrudge the MFA program’s existence. What did an MFA degree ever do to you? What brings about such impassioned criticism of the MFA?

At the root of the discomfort with the critique of MFA programs is an anti-intellectualism, which usually takes the form of assailing the critic’s “generalizations.” We do need to understand the philosophical moorings of an institutional system that by now recruits almost every literary writer in this country. Wallace Stegner’s dream has come true, and we have moved from “writers who teach” to “teachers who write.” (A really disturbing new phenomenon is the incorporation of commercially successful literary fiction writers into the academy, after they’ve made it big and presumably don’t even need the money; they’re proud to be asked to teach at Yale or UCLA or NYU or Columbia.) I’m not new in my attack on MFA programs—others preceding me include John Aldridge (to go back a while in time), and more recently Donald Hall, Joseph Epstein, Dana Gioia, Eve Shelnutt, Diane Ackerman, Vernon Shetley, Greg Kuzma, J. D. McClatchy, D. G. Myers, and many others. Most of the critiques of the last two decades have focused on poetry, while my analysis is very broad, tries to take in the whole picture, connects all the different institutions in play, and begins to imagine alternatives to the MFA system.

Just because it exists and is prevalent doesn’t mean it’s the right or best way. A particularly unfortunate recent justification of the status quo is Mark McGurl’s The Program Era, where he supposes that because the system is so dominant it must be for good reasons—it obviously serves certain self-interested constituencies, and from McGurl’s functionalist point of view, that’s good enough. I suspect that McGurl’s defense will be the high point of MFA orthodoxy in this country, after which the questioning and skepticism will erode the system’s legitimacy over time—and I certainly intend to play my part in its downfall, which will come not a minute too soon.

The question is not what an MFA did to me, but what an MFA does to you, Roxane, or to writers like you, to all honest writers in general. The MFA promotes and rewards a certain kind of writing, and forbids and punishes other kinds of writing. We have to accept that as a starting premise, because any institutionalized system will perform this function. So then the question becomes, What kind of writing does it favor? Within the parameters of MFA writing, certain writers look pretty damn good—Louise Glück, for example, or Aimee Bender, or Denis Johnson, or Marilynne Robinson. Outside its parameters, it’s a different story. I disagree that the MFA system is producing good, let alone great, writing. I’ve dissected in many reviews and essays the kind of writing being produced under the MFA system, and I consider none of it good or great, and the overwhelming majority repulsively bad. The system is churning out copy because of the oversupply of writers, but it won’t last—and I’m not the first one to attack it for its superficiality.

Among the things the MFA does to you: You can’t easily establish yourself as an independent literary entrepreneur because writing that is most rewarded takes place within the system. One reason why literary writing is so poorly compensated is because of this oversupply. It’s difficult to set yourself up as a publisher if you’re competing with the flood of mediocrity issuing from the system. We could argue that because there’s so much mediocrity, good writing will stand out even more, but we’re just being optimistic when we say that. The options for writers outside the MFA system have become radically diminished—and that’s a real problem. The hegemony of the MFA system deserves unsparing criticism. The MFA relies on overspecialization (writers work within narrow niches in one genre only), exclusion of literary criticism as we’ve known it, and separation of the writer from the mass reading public—all major concerns.

I read an interview with you where you stated that in order to learn to write well, one must study the classics, absorb the ways of the masters. Is there nothing to be learned from contemporary fiction?

In the early stages of a writer’s career, when influence is more easily accepted, I think it’s best to stick to the classics. It’s easy to pick up bad habits. So much of American storytelling—Antonya Nelson, Frederick Barthelme, Mary Gaitskill, Maile Meloy, that monstrous new writer known as Wells Tower—is absolutely destructive of how a writer should approach the story. If you have extra time, why not go back to Chekhov—again and again and again?—since you’ll learn more from one story of his than a lifetime perusing the likes of Nelson and the living Barthelmes.

The contemporary American story is terribly constrained by a few arbitrarily-imposed rules of realism, very artificial in form and structure and thematics, and founded in a regressive aesthetic, which it’s amazing to see making a comeback after the heights of modernism and postmodernism. American poetry is likewise terribly impoverished today; there are great classical examples to follow and learn from, and poetry written in other parts of the world—Eastern Europe, for example. As a model to follow Antonya Nelson is easy, because instead of organic connection between the writer’s reality and the deep structures of the world in a global, universal, historical sense, and being similarly connected with the tradition of writing over the centuries, what you have is replication of mundane experience for its own sake. This is true of American poetry as well, Stephen Dunn for example.

I see a break having occurred in American writing after World War II, a pulling back from inventive energies which has had a cumulative half-century effect, and this is why one must treat this body of writing with some skepticism. There have been great writers anyway—Richard Yates, or Jean Stafford, or, despite the institutional limitations, John Cheever. And there have been many wonderful poets in the post-war period. Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland is a very important book of the last decade; I don’t see any American writer being able to pull off a book so at odds with the optimistic, cheerful, sociable, delusional American writer’s world of make-believe, a devastating critique of empire in its last stages. Give me a book like that, and I’ll read contemporary fiction.

There are fantastic European and Latin American and Asian and African writers among the contemporaries, and of course one must learn how they address current reality; that’s not something you can get from the classics. I think Orhan Pamuk, Salman Rushdie, and J. M. Coetzee are the world’s three best contemporary writers, in that order, and beneath them are so many other writers who offer fresh looks into consciousness and reality. One must study all of them—as long as Chekhov and Forster aren’t getting short shrift. You “compete” with your contemporaries in very different ways than you do with the classics; you need both these relationships in order to be a complete writer, and you need to let frustrations and envies and resentments and admirations fester and fertilize in complicated ways if you want to do something original.

In a lot of your criticism I detect a real sense of fatigue with modern letters. I, on the other hand, feel like this is a really exciting time as both a reader and a writer. There is, indeed, so much writing out there but so much of that writing is so damn good. Where does your fatigue come from? Is there anything about literary culture right now that inspires you?

It’s not fatigue, it’s a rational criticism of illegitimate literary institutions. And if you follow my work at the Huffington Post and in print, you know that I spend far more time promoting underappreciated writers, especially young writers, than I do taking down the likes of David Orr and Jonathan Franzen. Unfortunately, the negative criticism gets infinitely more attention than the positive criticism. I have to add that the ambition of young American writers today is severely limited, and even when I admire their work I feel they could be doing so much more. But then one gets into the practical issue of acceptance and publication. If you write a challenging long poem in the tradition of Williams or Dorn, who is going to publish it? Likewise for a novel that bucks convention. Criticism is dead for now—it’s mostly mutual flattery. I cringe at the rampant Internet cliques wildly overpraising in-group writing—there’s some verbal ingenuity there, but the flash fiction and prose poems are generally very minor, even trivial, and have a mechanical, workshop-exercise feel.

But I reject the idea of fatigue. I’m really turned on by developments in world literature. I believe that within the next couple of decades we’re going to move to a global market in literature, so that trends in one place will affect those in every other place; just as the economy is one connected whole, the same will be true of literature. That will be very exciting. For example, I see publishers in India already taking the lead in promoting exciting writing; this is only the beginning, and you’ll see the initiative coming not necessarily from the present metropolitan centers of the world but from the supposed periphery. The new cosmopolitan outlook is going to change everything; I’m terribly excited about that. I’d like to point to Rana Dasgupta’s Solo as an exemplar; where do you place the book, what region and national culture does it belong to, who is its ultimate audience? These are impossible questions to answer in the old ways: Dasgupta is a British-born writer who lives not in New York or London but in Delhi, and his novel re-imagines the history of Bulgaria in the twentieth century. It’s one of the first truly global books of the current era.

How does it feel, as a critic, when harsh criticism is directed to you? How do you respond to what your critics have to say about you?

I have the thickest skin of anyone you’ll ever know, and that’s helpful when you attack as many sacred cows with as much venom and fire as I do. The most disgruntled public responders have been those in the MFA and publishing hierarchies who feel threatened that for the first time the inside business of writing and publishing is being aired for a mass public online with such lack of concern for polite conventions. Dan Chiasson, formerly of the Paris Review, wrote after my overrated essay that I should be blacklisted by publishers; some other entrenched writers spoke in similar vein.

I feel inspired by the fervor of private messages I get in support of my views; you’d be shocked at the kinds of people in the very highest reaches of publishing and writing who support me; they can see the problems too, but it’s not possible for everyone to just come out and say it. The attacks are often personal—he’s bitter or unsuccessful or failed, or he’s too successful or part of the system or an insider—and I can dismiss that, but a lot of it reflects the anti-intellectuality of American writing; writers in the age of new media are required to behave by kindergarten rules of politeness, saying only nice and pleasant things about other writers and about the writing culture.

There are many, many blogs that ensue in response to my criticism, and I’m very happy when sometimes they engage with the substance of my arguments. I would like to see much more of that, systematic refutations of my logic, if necessary. If you think Jorie Graham is a good poet, let’s hear it, defeat my propositions, or if you think the Pulitzer Prize is a good barometer of worthy writing, then let’s hear your arguments. If you disagree with my interpretation of the psychology of the writing workshop, then let’s hear about your psychology of creative writing.

How do you read when you’re going to review a book? How much do you read in a given week? Are you able to read for pleasure?

I read way too much for my own good—for the good of my imaginative writing, that is. If I like a book, or if I’m going to review it, I read very slowly and systematically. I’ll read, even for an ordinary newspaper review, everything the writer ever wrote—certainly for a poet, and for fiction writers with huge oeuvres, as much as possible to situate the book in the author’s history. I’ll probably read a lot about the history and politics and art of the region or era in question. I’ll make extensive notes in the margins as I read, and scribble twenty, thirty, forty questions in the back of the book, versions of which might become the basis for the review or the interview. I read constantly—pretty much every bit of time other than writing and whatever I need to do for sheer bodily survival. I read not just literature, but extensively in the social sciences and humanities and arts. I manage time to the minute, and I think the discipline acquired from my corporate period (hah! I surprised you, didn’t I?) has something to do with the obsessive measurement of time.

By this point, I’m pretty much unable to read for pleasure, which is a great loss. There are so many venues and opportunities to treat books in a critical manner that it’s become almost impossible to read for pleasure alone; the only authors I can say that about are those, like Proust, whom I’ve decided not to treat critically.

Right now, on one shelf of the bookcase next to my bed, I have these books lined in order: Beckett’s Murphy (must get a grip on Beckett), e. e. cummings’s collected poems (much underrated, maybe because of his conservative politics?), Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (I still haven’t come to a final conclusion about Pynchon), DeLillo’s Americana and End Zone (his first and second novels, and I want to say some new things about his novels of the seventies), Clay Shirky’s Cognitive Surplus (very much after my own heart in his positive take on the Internet’s social potential), Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (I love the lack of hesitation in the language), Coetzee’s Dusklands (must write a comprehensive essay on Coetzee), Alfred Kazin’s Starting Out in the Thirties, Nabokov’s Ada (ah, Nabokov, one of my greatest inspirations—now this I do read for pure pleasure, because I have no desire to critique him, and I have no idea what he’s up to in Ada and I don’t want to know), Gass’s Omensetter’s Luck (radical experiment with language), Mailer’s An American Dream, Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop (for pure pleasure and for sleep inducement), Pamela Haag’s Marriage Confidential (yes, abolish traditional marriage, please), Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Eugenio Montale’s Otherwise (I love the Italian hermeticists, particularly Ungaretti), Tomas Tranströmer’s collected poems, Italo Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience (to finally finish it), Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, Lan Samantha Chang’s All Is Forgotten, Nothing Is Lost (the head of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, up to the usual tricks), Herta Müller’s The Land of Green Plums (did the Nobel people know what they were doing?), Adrienne Rich’s poetry (for an interview), Martin Espada’s poetry, W. S. Merwin’s poetry (for an interview), Jay Parini’s The Passages of H. M. (for an interview), Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity, Naipaul’s The Mimic Men (among the greatest writers in the world), Konstantin Fedin’s Cities and Years, Ha Jin’s Nanjing Requiem (I’m reading all his work), and Clayton Eshleman’s poetry (for an interview). Eventually most of this will materialize in some form of criticism. Dickens and Nabokov and Stendhal, people I’m not thinking of critiquing, are perhaps my only sources of reading for pleasure—and the greatest poetry, which I can read again and again, without feeling the pressure to comment.

What’s the last great book you read?

The last truly great book, of historical proportions, I read was Orhan Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence, which stands well with his greatest novels like My Name Is Red and The Black Book. The ambition of Museum is colossal—and the writing technique poses so many challenges that a fiction writer can lose himself in it and acquire everything he needs to know for a full-blown career, from this book alone. Also around the same time, Coetzee’s trilogy, Boyhood, Youth, and Summertime, which is as close a reading of the spiritual ambience of my own childhood and adolescence (though not mature adulthood) as I’ve ever read; I actually followed most of the prescriptions in Youth for a budding writer—including the monkish life and no sex or relationships—for considerable periods of time. I recently read/reread all of Salman Rushdie’s writings, and I can’t express how highly I think of him; The Satanic Verses—though wrapped in needless controversy—may well be his most original, inventive, and rebellious book. I wish he’d continued in that direction, but he didn’t; that’s a book people will be reading for eternity, hopefully for all the right reasons.

What do you love most about your writing?

That it organically blends the intuitive and the rational, that it suggests much more underneath the surface than visible, and that it strives for a new language, whether it’s fiction or poetry or criticism, because if a writer isn’t trying to discover new ways to shape language in response to the needs of his time, then he’s shirking his ultimate responsibility. I’m the happiest person on earth to be able to write as I want to, without having to follow limits and expectations.

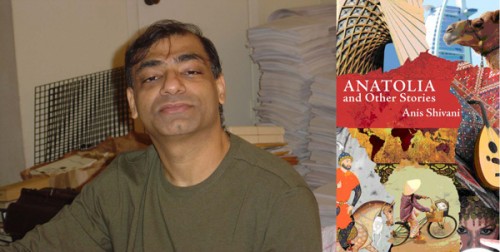

Anis Shivani’s books are Anatolia and Other Stories (2009), Against the Workshop: Provocations, Polemics, Controversies (2011), and The Fifth Lash and Other Stories (forthcoming, 2011). He has just finished a novel called Karachi Raj, and is starting a new novel called Abruzzi, 1936.

Tags: Anis Shivani, criticism, Huffington Post

I’m afraid to say anything.

“There’s no rush like writing fiction, and I can’t do it on autopilot, as it’s possible to do with criticism or even poetry at times.” This is a rather astonishing statement from a so-called critic.

I came up with a caricature/impression of Anis Shivani while reading this. it goes:

NICE isn’t REAL. They teach that in SCHOOL. In the REAL WORLD everyone is MEAN. DEAL WITH IT.

that aside, the interview makes me feel weird because I find his attitude unpleasant, but I can’t disagree with a lot of what is on, for example, that 15 overrated writers list. I don’t like Billy Collins or Jorie Graham or Louise Gluck or Sharon Olds all that much either. but I think maybe that list isn’t all that controversial in content. Or, yes, it is because it got a ton of attention so clearly there was something controversial about it, but what *I* found wrong about it was to take those writers and say “these writers suck, and so there’s proof that the academy is evil.” I think it wouldn’t be hard to find some writers getting their MFAs or PhDs who *don’t* like those writers, or some writers getting their MFAs or PhDs who *do* like those writers. My first undergraduate workshop was taught by a phd candidate who confessed pretty much immediately that he absolutely hated billy collins. but maybe what I’m saying is obvious and I’ve missed the point of that list and all its controversy.

and what is it that people associate with the academy in literature, especially with poetry? do people have to write like bukowski to be non-academic poets? because I think there’s a *lot* of poetry coming out of the academy that is absolutely nothing like fucking billy collins, or jorie graham, or louise gluck.

anyway, one last thing, and this to you, roxane, and not anis. you said “I suppose that is the mark of a critic who is doing their job effectively–inspiring a reaction, a conversation, a response to their ideas.” I don’t like this that much. I hear it all the time though, “well it pisses me off, but at least it’s a response.” I hear it also about things like shitty movies: “well I hated it, but I’m talking about it so it’s a success in that sense” or also I once was talking to my ex-gf’s dad about how much I didn’t like carlos mencia and he said “well two guys in rural missouri who have never met him are talking about him, so I guess that’s good for something”. I disagree in all cases. if a filmmaker makes a film thinking that as long as someone responds to it, even with total hate, it’s a win, that’s dumb. if carlos mencia is happy being talked about, even if it’s shit talk, that’s dumb. and if a critic’s job is to get a response, even if that response is total disagreement and maybe even outrage or anger, that’s a fucking dumb job. in my opinion, at least.

in my opinion a critic should provide criticism that is thoughtful in at least some sense, and provoke a response that is thoughtful in at least some sense. I think this definition is loose enough, but I do think it removes things like “god damn this critic is dumb” or “this guy is clearly just trying to stir shit up”, and I also think it removes hyperbolic praise that is also something of a problem in small press lit (that discussion is also sort of boring at this point, though, you hear it all the time in comments at htmlg, and I’m not interested in playing that out again either).

I don’t even know why I’m commenting. I’m on pain killers from having some teeth surgically removed. so I have an excuse for sounding like a jackass.

Anis Shivani, in much more wordy fashion, is channeling Nabokov in Strong Opinions. He’s making some extremely valid points here – and I sure would like to see someone, anyone, challenge the substance of his arguments.

sorry I said “this is to you, roxane” like I was being confrontational. I’m not trying to fight you or anything. that was bad phrasing.

If you read his “criticism”, I don’t think you’d be surprised he writes it on autopilot.

“By this point, I’m pretty much unable to read for pleasure, which is a great loss.”

<—I can tell.

This interview successfully makes one of Shivani’s key points: the collision between two individuals who do not agree has produced the sort of charged, idea-saturated exchange that seems altogether too rare. Much respect to Roxane for engaging in the conversation, much respect to Anis Shivani – even when I don’t agree with his specific opinions, I do agree with the study, effort, thought, and independence that went into their formation.

I WAS A FUCKING REBEL AT HARVARD

i enjoyed reading this. glad you interviewed him, Roxane. i like his free thinking and hope for literature/potential of the internet, and i dislike some of the same writers he does.

i’m not a fan of the institutionalization of Literary Fiction because of what i see as an associated stifling of free thinking. i am excited about how the internet enables writers to bypass most or all gatekeepers between them and readers and potentially connects them to like-minded or stimulating fellow writers and encourages free thinking.

arguably the online cliques he speaks of and the complimentary reviews he speaks of are not indicative of a dearth of good criticism but rather in the first instance a modern version of IRL cliques in past eras and in the second instance a devaluing or even dismissal of the notion that criticism can and should strongly influence literary culture. it makes sense to me, though, that Shivani wouldn’t enjoy, as a “serious” critic, reading so-called reviews online that do not have the intent or style of most professional or critics’ reviews.

Kudos go to Ms. Gay for engaging in this discussion.

Its actually pretty interesting to go onto the guy’s website and compare the exceedingly large collection of publications — in literary journals — he has with the minuscule amount that most other people have. The best kind of “rebel” usually comes out from within the establishment; someone who did what the establishment asked, played the game, and then realized, wait, the whole thing was a scam from the get go. Now he’s out to expose it. Given the immense number of publications he’s racked up he’s someone worth listening to. If even someone like him says there is rot, then there must be rot.

What’s interesting is that he is viewed as the “outsider” and we understand ourselves as the “insiders” (or at least not as fringe as him); but in reality he is the insider and we are the ones looking in from the outside. That gives his criticism and opinion increased cache.

Disagree that he is viewed as an outsider. He wants to claim that cache, but who doesn’t? Newt Gingrich calls himself an outsider in his campaign. You are correct that Shivani is an insider and should be viewed that way.

Roxane Gay: why on earth would anyone find the fact that you always disagree with Anis somehow inherently interesting or worthy of comment–by you yourself, no less. Who the fuck are you? Franz Wright

I am someone who inspired you to make a pointless comment on a site where I am a contributor and where I regularly post about my opinions. That is who the fuck I am. If you don’t care what I have to say, don’t read what I have to say.

I think the real question is: Franz Wright, who the fuck are you ?

“You don’t know me, you don’t know anything about me. What you are is a sheep who has accepted the word of other sheep. I feel nothing but contempt for people like you. I sacrificed my whole life, for about forty years now, to do this thing, to pursue poetry, something which has no value to Americans, and has meant long stretches of poverty and even homelessness. If you actually know anything about my work, all I can say to you is–did you think I made it up. Do you grasp that after a catastrophic and abusive childhood I also then had to deal with extremely severe mental illness as well as addiction. You can have no way of knowing what I struggled with and still struggle with, in order not succumb to these illnesses, and having someone tell me about a blog like yours does not contribute to an already fragile sense of self, a person was beaten up throughout childhood by a stupid and brutal stepfather, who never lived in one place long enough to feel that anyone on earth is his home, who has lived for decades with the shame of mental illness, the inability to have anything like a normal life, a person who happens to have one talent and who clings to it to save his life and one who is actually all too willing to agree with those who put him down–you get the idea. Why the fuck would you want to cause more pain to someone like that. It is an indication of stupidity and cruelty and a moronic inability–as,, agfain, you claim to know my work–to put yourselkf in someone else’s place, to understand how you might feel if you stood in their shoes.” – Franz Wright

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Wright

“Awards

2004 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, for Walking to Martha’s Vineyard

Whiting Fellowship

National Endowment for the Arts grant

PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry [2]

1989 Guggenheim Fellowship”

Profoundly well-written comments like his above have restored my faith in the Pulitzer committee.

“I’m a “pretentious ass” according to whom?–a faceless nobody” -Franz Wright

holy moley

LOL. Ms. Gay got proverbially “pwned” by a big-timer.

I am curious: when you saw the name “Franz Wright” did it at least OCCUR to you to take a moment to question your self? I doubt it.

um lol what

why is a proverbial “big-timer” posting some pissy comment here without taking a moment to question what he’s doing?

why are “big-timer” poets so pissy about everything at all times

Excuse me postitbreakup: who are you for dismissing Franz Wright’s Pulitzer. Why? Have you read WMV? Also, I doubt his comments at some tiny blog get evaluated for Pulitzers. Then again, you try and workshop your stories on blogs, so you maybe you have exceedingly heightened regard for the blogging medium; maybe you think it should replace the Poetry category at the Pulitzers.

I really don’t know. I can most definitely relate to being mentally ill and coming on message boards to be shitty, but I’d like to think that if I had a career I was proud of (or could at least write a publishable story again) that I’d grow the fuck up. It’s bizarre. When I’m a dick it’s because I hate myself extra that day, so maybe the same thing applies to Franz? But if you can still hate yourself after winning a Pulitzer . . . Depressing, depressing, depressing.

uh-oh pulling out the big guns

I wasn’t saying he didn’t deserve a Pulitzer, I was pointing out that it’s fucking shocking that someone who’s allegedly so high caliber would post something so shitty on a blog.

When I was in school and had access to writing workshops, I used those. I graduated. I don’t have that option any more. Thanks for clicking on my blog, though.

Why u mad tho

why do people keep asking who people are? should we do some introductions in this BLOG THREAD or can we all just agree to imagine we’re all humans somewhere

hahahahahahahahhahahahaha holy fuck

I don’t think you know what “pwned” means.

I don’t think you know what “pwned” means.

do big timer and poet belong in the same sentence, EVER?

CAN WE GET SOME PRIZEWINNER INTERVIEWS UP IN THIS PLACE OR WHAT. WHO ARE ALL OF YOU I’M READING.

Have you ever read the Hunger Games? Pretty fun series, man.

Hi, my name is Adam. I like reading and websites.

Do any poets wear chains or have good cars?

Hah. This is great. It’s like an SNL skit or something.

I’m Gay

I know what you mean, Rebekah. Sometimes, Anis reminds me of Anders from Tobias Wolff’s “Bullet In the Brain” and it makes me sad, and I wish he wouldn’t need to get shot in the face to remember how beautiful language can be.

I hope Shivani starts commenting here.

I hope this is really Franz Wright. He’s a ok dude.

I’ll even settle for a poet with a not-used bicycle.

Incidentally, why do people really assume this is Franz Wright? That’s absurd. THIS IS THE INTERNET.

Look, I like websites so I know- usually, other people tell you you’re gay.

I am a butt. Franz Wright

Yes.

My bike was purchased new and at cost.

My bike was purchased new and at cost.

Re: postmodernism.

I don’t get how one can be that intellectual and also be so sweeping in his dismissal of others who were also truly that intellectual.

Re: Chekhov.

Are you kidding me? Maybe it’s just a bad example but everybody has a vestigial Chekhov organ inside them. Some nourish it. Some ignore it. Some cut it out. Isn’t that kind of pleading for the sameness he reviles? I love love love Chekhov but rarely write like him and am glad there are 31 flavors. Chekhov gets at the human, which is undeniably important to lit, esp. if one sees it as a moral undertaking, and his writing is a great (dare I say) model for a certain kind of story – but it’s become a different world in too many other ways.

Franz Wright sort of has a history of this shit: http://jjgallaher.blogspot.com/2010/05/franz-wright-critique-of-mfa.html

although I guess that could have also been a fake Franz… dang.

haha, this reminds me of that great Simpsons line, before the show sucked, where Milhouse, all puffed up, tells Bart his dad is “a pretty big wheel down at the cracker factory”

or in Franz Wright’s case, the cracka factory

you know, you are right that putting the stories on the blog didn’t work and was lame, i dunno what else the fuck to do. i don’t have any friends really, but even when i did they weren’t big fiction readers. i did the maximum number of fiction workshops my school would allow (3).

if this anis guy has any point in all his bullshit it’s that it is harder to be writing without an mfa but i’m not even talking about some publishing conspiracy like he’s implying, i miss the workshops. i don’t know what to replace them with. it seems pointless to just send a story i know isn’t at its best out to 10,000 magazines hoping someone has bad taste. my writing teacher from school said he’d help and such but that hasn’t really worked out and he’s understandably busy. how does anybody get anything read anywhere

[…] via A Conversation With Anis Shivani | HTMLGIANT. […]

My interview of Shivani can be found here: http://impressionsnthoughts.blogspot.com/2011/02/write-what-you-dont-know-interview-with.html

Here he discusses his first collection of short stories ‘Anatolia’ in addition to other things.

Yeah, I meant really.

the road not taken

A fair challenge.

This plan would “replace” nothing, as it is already the ‘mission’ of English departments and (I’m guessing), to a lesser extent, creative writing programs in American universities. There’s not much bold or independent about telling institutions to do better at what they’re claiming to be trying to do already, nor is it constructively provocative to sneer at a value – like “craft” – that’s not substantively being questioned.

A bad thing, to favor without reasonable discrimination. The promotion of “multicultural” literature that I’ve seen often promotes the “fantastic European and Latin American and Asian and African writers among the contemporaries” that Shivani himself praises here; the difference is . . .?

The caricature of recent (and ancient) interrogations of reason (among other planes of “privilege”) that Shivani indulges in here is too reduced to code-sneering to argue against (or to support). Distaste merely for the popularity of, say, deconstruction is no “intellectual” perspective at all.

Most readers will agree with some particulars to be found in Shivani’s spray of discontent To me, that spray is inconsistent to the point of being indistinct from lazy, however energetically it’s expressed.

“What It Says About You: if it is a headshot, author photo, or

other promotional material, it means you are a narcissistic careerist.

If it is a self portrait, you are slightly annoying.”

http://warmedandbound.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/bulter.gif

http://htmlgiant.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/shivani.jpg

A big name is no excuse for being rude.

Postitbreakup:

You are torn between sucking up to the people that might workshop your stories (like most of the readers of this blog) and agreeing with Anis who says that the whole idea of workshopping is a bunch of bullshit.

My advice is to go the Anis way. Forget workshopping. Forget thinking that there is some Platonic form in the sky resembling the ideal short story which workshopping will get you to. Instead, write the story you want to write, then write it 100,000 times more. Everyone from Chekhov to Joyce to Faulkner and Phillip K. Dick. You think they were workshopping?

I am sorry that you “did the maximum number of fiction workshops my school would allow.” They destroyed you. Here is what you replace them with: the lonely struggle of lonely work. Read that Franz Wright quote above. It exemplifies the struggle. Stop hanging out with these people. They don’t want to help you.

Uh, yes they do. Are you trying to be ironic or some other relative of hipster? I am a prose writer but even I know poetry is harder. Prose writers like Salman Rushdie admit that what they look to for inspiration are the poets. And the same hold true among French novelists. Maybe your contempt towards poetry is why you are not interesting. Fucking Plato.

Is that a pile of folded napkins behind Shivani? Makes me wonder if all Houston households have big piles of napkins.

Hello deadgod,

I have to agree with your first point. Shivani paints with quite a broad brush here, and by the very fact that some writers (Shakespeare, say) are studied intensely and others less so, indicates that some judgments as to good and bad are being made. Maybe the distinction he wants to make is that English departments often study literature as text, rather than making judgments about the literature itself. I dunno.

To your second point, I think Shivani is not referring to international literature, but multicultural literature within the US. I wish he’d provide some examples, though.

On your third point, I think that to some extent, Shivani is right – some of the biggest critics of “reason” were some of its biggest beneficiaries, in terms of place in academia. But, yes, a critique of rationality, per se, is almost as old as rationality itself; Derrida is part of a grand tradition.

I will say that, rhetorically speaking, the energy that Shivani is part of what makes it interesting.

meanwhile, jerry saltz makes similar complaints in visual, http://nymag.com/news/intelligencer/venice-biennale-2011-6/.

No that’s a visual representation of the interior of your mind.

I’ll bet a pile of napkins and a bottle of hot-ass Houston pepper sauce that “Calpurnia” is Shivani.

Maybe. Probably.

I don’t think you “get it”

I mean, to your last paragraph… 200 posts and 78 stupid “likes” didn’t lead to a single comment or email about my fiction. I’ve probably written 20,000+ words engaging with people’s shit (in both negative and positive ways, certainly) that more people have read than the 900 word story I was looking for comment on.

I don’t know if the fiction workshops destroyed me or not. Certainly my depression/anxiety/what-they’re-now-calling-“borderline” destroyed me. In the workshops at least people engaged with my writing, even if it was to trash me. But at the same time, I stopped writing after the workshops. Cause or effect, who knows. But I see your point.

“I don’t doubt that this entirely atypical book would have caused

anything but nervousness among the vast majority of small press

publishers who like to imagine themselves as mavericks and

talent-spotters.” -AS

_______________________

He is over-the-top and generalizes way too often, but I have to agree with this point–I was nodding my head here, yes.

There are, of course, exceptions–don’t get me wrong–but most of the small press work out there is fairly conventional when you actually read past all the hype from editors who think that anything small press somehow entails “innovative.”

I think he’s also right about many of his points in regards to a lot of the flash published today. Don’t get me wrong–I love flash–but too much of it reads the same; I read way too many “slice of life” flash fiction stories online that read similarly in style and tone to other slice of life flash fictions proliferating the Internet. They might be well-written–and many of them are–but I would like to see more diversity in the kinds of flash that are represented, beyond slice-of-life realism.

Just… can’t… resist…

Does Shivani know what “overrated” means?

You would have to ask him, wouldn’t you?

Well, I like accurately vigorous hostility, but, to me, Shivani hits his thumb – as well as perfectly innocent wood – way more often than any nail-head.

I don’t think Shivani is actually going at multicultural “literature” (though that is the term he uses); he’s irritated by a “multicultural” agenda – one that would stupidly exclude, say, Shakespeare. – but, here, he employs a multicultural agenda!: ‘Americans really should read the great and even the good contemporary literature of the rest of the world.’

He would make of being grumpy an intellectual as well as a moral virtue, neither of which it is; it’s a style that, to me, commits its embodier neither to being reasonable nor crazily partial.

“I am a prose writer but even I know poetry is harder.”

So fucking stupid. Do people really think things like this?

yessssssssss

BTW–and I’m sure AS has a sense of humor and can take this–but dude has the biggest eyebrows I’ve ever seen.

Nah. Too succint.

I’m not Shivani. I’m a lurker.

Sad thing is someone like you bashing Shivani though. He consistently gives small presses more love than any individual critic I’ve read lately. Not just at Huff Po but everywhere. And not just in fiction but nonfiction too. Read his tearing of the NYTimes Review Section. The whole critique is about their disregard for the small press. But you just go on and bashing the dude without knowing much about him or snickering stupidly at snark.

Put that sauce on a napkin and wipe your a$$ with it.

?

Well, I sure can’t tell from the way he uses the word in this interview.

[…] enjoyed this (long!) interview with Shivani at HTML giant and I could excerpt a dozen things, but this is what I am thinking most about at the […]

[…] Roxane Gay chats with Anis Shivani […]

Glad he has a thick skin, because he’s kind of a fookin tool.

Anis Shivani: the Ann Coulter of literary criticism

Exactly Court. Having “followed” Shivani for a number of years, I was convinced from the beginning he was channeling Nabokov. I happen to agree mostly with his ideas, and I enjoy his prose. I also have read many of Roxane’s fiction pieces and essays and enjoyed them…and I realize that she swings the opposite way of Shivani’s beliefs. But, as these things go with art, I am always happy to see fruitful discourse of opposite opinions/ideas. In the end, most of us writers are trying to make an enjoyable (semi?) comfortable living, and support our families (for those of us who have them), or dependents. Our product cannot possibly appeal to everyone. Nor should it be crafted and/or compromised (enough) that it does.

[…] A Conversation With Anis Shivani | HTMLGIANT. […]