Literary Magazine Club

{LMC}: An Interview With the Editors of Salt Hill

I love talking to other editors about editing, how they run their magazines, and what they’re thinking about the state of the literary magazine. I had a chance to talk with the editors and designer of Salt Hill to get a sense of the view from Syracuse.

Tell me a little about the history of Salt Hill. Where does the name come from? How long has the magazine been publishing.

Rachel Abelson: The journal has been around for about fifteen years. We are approaching our 30th issue. I’m not sure who is responsible for the name—Michael Paul Thomas was our founding editor—but it’s a reference to the geology of Syracuse. Most of the salt in this country came from Syracuse way back when. There’s a whole museum dedicated to salt here. I believe they reenact the mining of salt pre-1900. I guess Onondaga Lake, besides being wildly polluted, is fed by brine springs. There’s also a lot of snow and a good deal of road salting, too.

Gina Keicher: Salt Hill is run by graduate students in Syracuse University’s Creative Writing Program. It’s a fitting name for a journal based out of the “Salt City.” Also, Syracuse’s campus is situated atop a rather massive hill, so there’s that as well.

What is your editorial process like? How are decisions made? Who has input?

RA: It’s a collaborative process, but there is some autonomy, too, which is key. We often have multiple editors for each genre—poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and art. The goal is for us all to be proud of each section but to avoid editing the life out of something just to ensure we’re unanimous on the matter. Each genre editor is often responsible for a handful of pieces: work they solicited or pulled from slush. These are a genre editor’s babies. And then genre editors work together to build a section around their babies. Editors-in-chief manage separate genres while being responsible for their own pieces as well. Our readers suggest solicitations, too. We’ve worried in the past about over-editing individual pieces. Too many cooks in the track changes. We’re all in MFA mode right now, so we’ve maybe acquired a dangerous instinct to workshop the universe. A degree of editorial autonomy has been our way to respect the stylistic integrity of each piece. If an editor is stoked about a story, she is who will be working with the author on edits and proofing. The logic being: if you like it, you’ll maybe do it justice.

GK: Over the past few years, we’ve also aimed to streamline the process by switching to an online submissions manager, eliminating the paper shuffle. Unsolicited submissions are assigned to readers. If a reader likes a piece she passes it onto the genre editors. If the genre editors are enthusiastic about the piece it goes on to the editors-in-chief. Ultimately, the editors-in-chief make the decisions as to what goes into the journal, taking into account the feedback and comments we receive from readers and genre editors. Throughout our production schedule, editors-in-chief regularly check in with each other, as well as with the genre editors, to determine what may be needed to round out an issue.

Who designs Salt Hill, and how do they come up with the aesthetic of each issue?

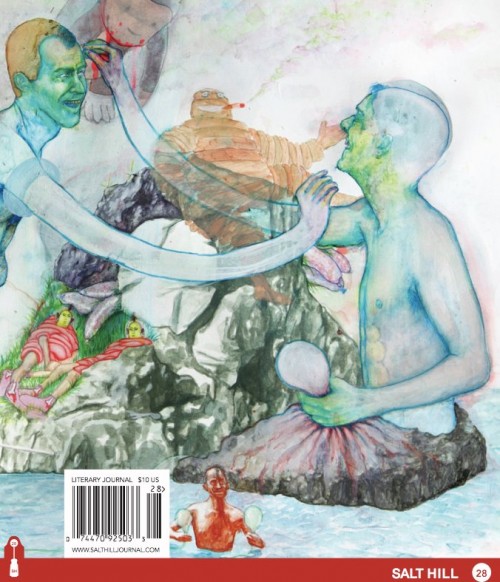

RA: Nadxieli Nieto Hall at NIETO Books (nietobooks.com) is our brilliant designer. When a grad student at Syracuse, Nadxi started designing our issues (and also served as an editor-in-chief, as well as the art editor and nonfiction editor) and during her time at Syracuse she revamped the entire design aesthetic to how it has looked for the past five years. Nadxi was also instrumental in making visual art a more prominent component of the journal. Today we receive a growing volume of unsolicited art submissions because of this. The overall visual aesthetic of each issue is determined first by the art editor, who usually reads a sampling of accepted work from other genres, consults with the editors-in-chief to solicit art that plays nicely off content, and then works with Nadxi on layout. We’ve been working on creating more crossover between art and the journal’s other genres. Our upcoming issue, for instance, includes both a comic by Aaron $hunga, excerpts from a larger illustrated book by Faye Moorhouse, and drawings by cyberpunk writer Rudy Rucker. Issue 22 included Stefanie Posavec’s visual analyses of Kerouac’s sentence structures in On the Road, and issue 25 featured drawings by poet Michael Burkard.

Nadxieli Nieto Hall, Designer: Salt Hill is a wily beast and I love a wily beast. The main challenge is trying to keep the design somewhat consistent while allowing the editors-in-chief—which change every year—and art editors, to express their own aesthetic. It’s surely not something we’ve perfected, and some issues are more successful than others, but it is a good challenge issue to issue.

How does the magazine maintain continuity from one year to the next with the transitory nature of student-run magazines?

RA: Salt Hill doesn’t have a prevailing literary aesthetic on its sleeve, but the journal is a kind of microcosm of the readerly tastes of the Syracuse program. We’re not a one-vibe kind of place, but like any MFA program, there are vibes that tend to reoccur. So, in that sense, we don’t encounter a tough time hitting notes in certain registers again and again. But the practical how-to’s of managing and publishing a journal, yes, the turnover makes things difficult. We have a fat, three-ring binder that is passed down through the years like some secret society torch. The binder usually knows what’s up. That, or the Gmail archives. Also having Nadxi on staff as our designer for all these years has been a blessing. She gets too many desperate, amateur-hour emails from us that she responds to with much grace.

GK: We’re very fortunate to have Nadxi’s design expertise. There’s something about Salt Hill looking the same from issue to issue that seems crucial to maintaining visual continuity. The journal is recognizable from one issue to the next. Content-wise, there’s carryover from year to year. All the editors have had previous experience with the journal in some capacity. Students entering the MFA program who wish to be involved with Salt Hill start out as readers, or as the Distributions Manager. By working on the journal, they get a feel for the work we publish and this tends to carry over to the next year when a few readers and/or the Distributions Manager are appointed genre editors.

What are some of your favorite pieces from Salt Hill 28? Why?

GK: One of my favorite pieces is Tony Trigilio’s “My soul sometimes floats out of my body./I don’t listen to the radio while driving.” I gravitate towards poetry that haunts via any number of craft-related feats—tone, image, subject, voice, to name a few that I think this poem employs to skillfully hit the mark. I also keep coming back to Oliver de la Paz’s “Labyrinth” poems. The prose poem form lends itself to the sustained bildungsroman narrative threaded through the five poems in Salt Hill 28. There’s also a bigness, perhaps even an epic sensibility, to these poems that strikes me. Also, I’m drawn to the dialogue in James Robison’s “Zurich.” There are interesting tonal and thematic echoes between this story and the art that precedes it from Frederik Heyman. I also find myself revisiting Casey Wiley’s nonfiction piece “Sgt. Slaughter” quite a bit. For me this nonfiction piece does description, voice, and nostalgia exceptionally well.

RA: I love Amy Benson’s “Outlaws and Citizens” and “Gone” from our nonfiction section. In these pieces, Benson documents her encounters with two art installations: video and projection artist Pipilotti Rist’s Heroes of Birth and the Starn Brothers’ “Big Bambú: You Can’t, You Don’t, and You Won’t Stop,” which was a massive, nest-like sculpture built atop the Met in 2010. Instead of functioning as art criticism—Benson never names the exhibitions or the artists—the pieces become lyrical reflections on the personal, real-time experience of immersive art. I’m also partial to Jason Schwartz’s “Housepost, Male Figure.” Schwartz’s domestic objects—fences, shutters, doorknobs—become so ominous and uncanny in his sonic, crisp sentences. John Madera’s interview with Mary Caponegro is something I will continue to return to as well. Her discussion on digressive, idiosyncratic, phenomenological prose is honest, funny, and inspiring. Few writers—Gary Lutz would be another—can speak as eloquently about the music of the sentence as Caponegro can.

What do you love most about editing?

GK: love encountering work that makes me excited about writing. Editing a literary magazine, I get to see some of the wide range of things happening in writing and that’s really exciting. Even if a piece isn’t the best fit for Salt Hill it’s still an enjoyable experience to come across such varying aesthetics and styles.

I also think it’s fun to be the one who contacts an author to share the news that Salt Hill is accepting a piece for publication. It’s satisfying to find outstanding work that will make an issue great, but that satisfaction is infinitely greater when the connection is made, contacting the author and witnessing that excitement.

I’m also fond of sequencing the book, the curatorial aspect to editing. Salt Hill doesn’t tend toward themed issues, but when we sit down to sequence an issue all the work seems to naturally coalesce. For example, in Salt Hill 28 so much of the content focused on the body, even though we hadn’t set out to search for work that addressed the body. The repetition and torque on this subject gave the issue a nice arc. It’s really quite eerie and perhaps speaks to some unconscious nodes that the editors-in-chief and genre editors mull over throughout a production schedule. I love that inexact science of editing. It’s an organized chaos. Each piece of content is distinct. Still, I’m always amazed at the cohesion, the echoes and reverberations we get across an issue.

RA: Besides the sequencing of each issue, I enjoy suggesting possible edits to an author. Thinking about how to improve a story without violating the author’s terms, keeping in mind his or her style and original conception of the piece while further refining its strengths. We are also cautious to honor an author’s grammatical choices and edit toward maintaining consistency across each piece in this respect. Meticulousness is rewarding. I also love when an author rejects an edit, especially when I believe I’ve come up with some inspired change and the author goes a different direction entirely or even better, flat-out refuses. I like to imagine us eye-rolling at each other across the internet. It’s an important lesson for writer and editor alike: learning what can go and what should never get axed and why.

When you’re done working with a writer, do you feel you’ve done the work justice?

RA: Justice in a cosmic sense? I don’t know, probably not. But there is an ingrained ethos at Salt Hill, which essentially amounts to that Wilde quote: a writer can survive anything but a misprint. After the alienating ordeal of submitting work to various publications—enduring rejection and setback, not to mention the xtreme endurance sport of actually writing—to have the work rushed to print or slapped together haphazardly is tantamount to heartbreak.

GK: It is a great deal easier, also much less time consuming, to send a rejection letter than to work with a writer on edits. But it’s satisfying to build a relationship with a contributor, to put in that time because I care about the work enough to get it firing on all cylinders. When a writer submits her work, it deserves attention and close reading, especially if the work reaches the stage of publication. I want the writers Salt Hill publishes to feel that the editors are attentive in their reading and careful in offering suggestions. Anything less feels like a disservice to the writer. So the short version is that I feel I have done the work justice when the writer and I have engaged in a conversation surrounding suggested edits and produced the most successful work possible.

As editors, are you concerned about the proliferation of literary magazines and the very crowded market? Why or why not?

GK: Certainly not. If anything the proliferation of literary magazines strengthens my belief that right now is a really exciting time to be writing. There are so many literary magazines available that it makes the challenge of creating a distinct and recognizable journal that much more rewarding when we succeed. It’s really satisfying to hear from contributors and readers who admire Salt Hill with all the journals there are to read.

Sending a rejection is undoubtedly my least favorite part about editing. But the large number of literary magazines means there are many opportunities out there for all kinds of writing, so there’s often a confidence that the work can find a home elsewhere.

RA: I don’t lose sleep over it, no. But I do think that given the crowded market and given the staggeringly good and innovative work available for free online, it behooves us paper-based journals to produce beautiful, singular objects. Small, student-run journals might consider emulating artists’ books more, aiming to assemble a more fetishistic product. Too many journals—regardless of the merits of the writing published—are indistinguishable when it comes to looks. Yeah, yeah: don’t judge by the cover, okay, but we don’t all have to be the string quartet on the decks of the Titanic, playing the same old dirge. We can be the string quartet in 3D. That’s one awful, clunky analogy, but the question sunken beneath it is this: faced with the given reality, why just go through the well-rosined motions?

What other magazines are you reading and enjoying?

GK: There are so many handsome journals to love. I picked up a few issues of Bat City Review and Gigantic at AWP that I’m really digging. Bateau selects some great work and is a beautiful journal. Each issue feels like an artifact. They publish striking books as well. I think Ninth Letter and New York Tyrant also are great journals that always have strong work happening in tandem with some nice-looking designs.

RA: NOON and Conjunctions are my mainstays. Recently I picked up the first issue of Unstuck, and it has quickly become a new favorite. I’m inspired by the projects coming out of Dexter Sinister and DIS Magazine.

What has editing taught you as writers?

GK: Editing has pushed me to recognize when my own work is not succeeding and how essential revision is to the process. It’s also taught me that belief in a piece is essential to publication. Editing inspires, perhaps even demands, belief in a poem or story, enough to publish work that’s operating at its best quality.

Also, to be on this end of the process increases my enthusiasm about submitting my own work and helps me accept any rejections. Because I’ve been in the position of saying, “We already have a story about ninja alien cats so while this is a good story, it’s too much ninja alien cats for one issue.” So in that respect, I’m more accepting of rejection as a natural occurrence in the submissions process. On the flip side though, having edited and sent acceptances, I know it happens, that this isn’t some weird numbers game, that if the work demonstrates quality writing and is a good fit for a journal, it will get accepted.

RA: Basically everything Gina said.

What are some trends you see in submissions?

David Nutt, Fiction Editor: When we get short pieces, say 1 to 3 pagers, they skew towards the strange, the surreal, the deadpan, the fragment. The longer submissions, and most of them are longer, tend to be nicely groomed, well-behaved animals. Sometimes too well-behaved. The humor is mild, polite. The tone is self-aware and sincere. In general they take relationships as their capital topic. Sepia-tinged eulogies for the halcyon days of adolescence, embarrassing moments from my idiot twenties, amusing anecdotes about amusing friends who suddenly turned into tragic figures one drunk night in an empty riverbed. That sort of thing. The weakest of these usually suffer from clunky exposition, needless and awkwardly shoehorned back-story, too much narrative handholding. The strong mongrels always leap out. They start fast, sometimes indecently, and plunge us right into the muck of things, plowing forward without bothering to heed the creaky mechanics of narrative convention. They come at their subjects a little sideways. Witness James Robison’s “Zurich.” In lesser hands this story would be a tidy slice of domestic melodrama. Instead it’s simultaneously manic, sweet, and caustic. Kind of miraculous.

GK: I’ve read and edited Salt Hill for three years now so I have seen such a variety of things come through the mailbag and, most recently, the online submissions manager. I’ve been on the poetry end of things so I can speak mostly to that genre. We receive a great number of prose poems, which is fantastic and exciting; it’s always interesting to see how the writer has adapted and used the form. Another trend is the series, which is most successful when it does its work in the manuscript rather than the cover letter. It’s nice to know the poems are from a larger project, but beyond that any explanation tends to make me disenchanted with the work. Sometimes there are also smaller trends like recurring words or themes. For example, I recall a span of time during which the word “cochlea” and memento mori were frequent occurrences in the submissions manager, though I don’t recall seeing the two together in any one particular packet.

Oliver de la Paz blows me away