Presses

Tangible Values

Is there anything journalists love writing about more than the death of the publishing industry? Every few weeks there is a new surge of articles and essays pointing at the sky, suggesting said sky is falling, even though nothing ever seems to reach the ground. Magazines are going all digital, they say! Print is dying! Print must be dying so we cannot look for fallibility anywhere else. In recent weeks, there has been a lot of talk about the merger between Penguin and Random House. Two massive publishers will become even more massive.

Today, The New York Times, published yet another article, predicated on the assumption that publishing is declining. As I’ve asked here before, has any industry functioned in decline as long as publishing? Medical doctors should be studying publishing because, clearly, the key to immortality therein lies.

Perhaps it isn’t that publishing is dying but, instead, publishing is being killed. At the popular Brain Pickings, Maria Popova wrote a footnote to a post about Jane Mount, an artist who creates portraits of writers based on their ideal bookshelves. The Ideal Bookshelf featuring Mount’s art and essays by each featured writer, was released today from Little Brown. It’s an interesting idea, beautiful art, and offers us the insight we seem to crave into how the minds of great writers work.

In her footnote, Popova seems appalled Little Brown wouldn’t allow her to reproduce more than three images from the book without involving their subsidiary rights department to negotiate a fee. She writes, ” If I wanted more (“wanted,” of course, meaning “wanted to speak highly of their book in front of a few million of my readers for free“), their publicist kindly offered to ‘get [their] subsidiary rights department involved, and have them create a contract and some kind of fee.'” A few million readers, in this scenario, should be just compensation for the right to reproduce Mount’s art.

I am no apologist for publishing. They are ass backwards in innumerable ways but I love books and I love that people love books enough to publish them and I need to believe that someday, they’ll sort themselves out on the issues that frustrate me the most—diversity, e-book pricing, a slowness in evolving.

This is the challenge we’re dealing with these days–talking about books and art we love, and making sure publishers and writers are compensated for it. This is the math problem we seemingly cannot solve save for a lucky few. There’s a lot to be said for the power of a few million readers and surely, that will translate into some sales, but the correlation is nebulous. There’s no real guarantee of compensation. With subsidiary rights, the publisher and writer will be paid in actual currency and they will know how much.

Popova’s frustration is understandable but her suggestion that Little Brown asserting their subsidiary rights is antithetical to the joy of books isn’t quite right. Of all the things publishing can get wrong, this isn’t one of them. The whole point of The Ideal Bookshelf is the artwork. People do love to hold physical artifacts but I’m guessing Little Brown is assuming that more people will simply see the images online and feel like that’s good enough for them, than will both see the images online and purchase the book. Again, it’s too nebulous, too uncertain, and publishing is a business. Businesses don’t like nebulous financial prospects.

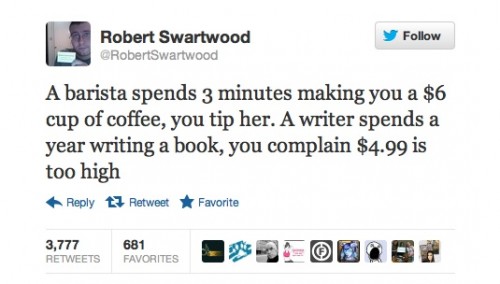

There seems to be a line people are not willing to cross when it comes to paying for art. On Twitter, Robert Swartwood mused about how we spend our money and how we value writing.

It was, as Swartwood notes on his blog, “just a tweet,” but it’s a tweet that gets at something fundamental about the value we put on art. We value art theoretically and seem, at times, to be less willing to value art monetarily.

We also talk a great deal about Amazon and how they are evil and swallowing up all that is good in publishing. Amazon is evil because we allowed them to become that way, because the free shipping is irresistible, because you can buy a brand new hardcover for 40% off, because we are willing to compromise the value of art to protect the value of our net worth, such as it may be. There’s no shame in this but we can talk about. We can admit this weakness in ourselves.

Some people look at the state of publishing and say it’s about supply and demand–too much supply, not enough demand. There is truth in that. We are drowning in books but I don’t necessarily see that as a bad thing because more cream rises to the top than doesn’t. They say more of us would buy books and magazines if publishers worked harder to put better work into the world but I read excellent writing every day. Though terrible books and magazines are published, so are excellent books and magazines. This is not about quality control.

I’d suggest that no matter how well-intentioned we are, a lot of us still feel like art is frivolous, that books matter less, that certain things should be free or cheap for the “greater good,” that art is a luxury. And yes, if it comes down to putting food on the table or buying a book, food it shall be. I’m talking here about people who are financially comfortable (ie. willing to spend $6 a day on coffee), and still are not really comfortable spending their money on things that are less tangibly consumed than a mocha latté.

Maria Popova clearly values books. Anyone who reads Brain Pickings can see that. Throughout her footnote, Popova discusses her love of Mount’s art but clearly, there’s a limit to that love, a financial one. She wants to talk about Mount’s art and feature art from The Ideal Bookshelf, but blames a dysfunctional publishing industry for not letting her do that for free. There’s…. a disconnect there.

Publishing isn’t dying but it is trying to keep its head above water in the ocean while rain falls down and people keep throwing buckets of water into that ocean, making it rise, rise, rise.

There’s a lot going on in this post, but Robert’s tweet seems like someone just excited to get up on his moral pedestal and point a finger at all the uneducated dweebs who aren’t smart enough to fathom the value of books. It’s snarky bs. A guy serving me coffee is engaged in a menial and generally thankless task that I don’t want to do myself. Actually, I’d rather pay him to do it. If he seems like a nice person, I’ll probably tip him. On the other hand, writing a book is an enriching and gratifying experience. (highly recommend it.) In fact, my barista might be doing this menial task specifically so he can engage in the awesome experience that is writing a book. Writing a book might be incredibly difficult to do well, but millions of people do write books in their free time. And, arguably, now that publishing one has become as simple as clicking “Publish” millions of people can participate in that as well. Which is totally freaking amazing. It suggests that publishing isn’t dying at all. Purely by headcount, there are 10-times more people engaged in publishing today than ever in history of humanity. That is the opposite of dying. What is dying is 1950’s publishing built on best-sellers and nepotism. This is what Maria is railing against. And I don’t think this is news?

So I was just at the grocery store. Clerk ringing me up, bagging my groceries, should I have tipped him? I sure as hell wouldn’t want to do ring up and bag my items. But, ya know, there wasn’t a tip jar. Should there be? I find it fascinating that in our culture certain professions are meant to be tipped, while others aren’t.

There’s self-service at Mall Wart.

–but yes, some service has evolved to be understood as compensated highly enough that personality is irrelevant (plumber), some service has evolved to be considered already paid-for in the listed price (cashier), and some service has evolved to include in it an agreeableness that’s to be compensated in addition to some listed price (stripper).

Perhaps a relevant political-economic distinction in the waitron/writer comparison is the uniqueness of consumption: the comestible hardware of a cup of coffee, you might share with one person… probably not, whereas the software of those words in that order, you might share with dozens, hundreds,–why not fantasize–millions.

Some of it, though, is the personal contact, right? You’ll spring for full hard-cover price at a reading – especially it you get to interact directly with the writer, but most books you read: no contact at all. With the coffee, the waitron actually talks to you (likely?). And you see this person, you understand the tiny hourly wage, the expectation that you’ll compensate or bribe or be extorted for service. The writing thing, that’s pretty far from you ponying at your computer or in the store.

The comparison in your tweet doesn’t work, even if your heart’s in the right place. I tip the barista after she makes my coffee. I don’t pay for a book before reading it (after vs. before). The book purchase is a gamble. Readers are willing to pay for books written by writers they trust.

All this is rather ironic in light of the post above yours, which champions self-publishing, since anyone can publish a crappy book and then price it. The fact that “more people are publishing” isn’t a sufficient an argument in and of itself. In many cases, literature benefits from gate-keeping.

Literature benefits from gate-keeping? Don’t be fooled into thinking Big Publishing cares about “literature.” A few editors might, sure, but Big Publishing is in it for the money. This is why every week a new Twilight fan fiction is snapped up by a major publisher. In fact, historically speaking, some of our best literature was initially turned down by many major publishers for one reason or another. So self-publishing means a lot more books, yes, most of which are shit, but it doesn’t mean literature can’t prosper because of it either. Of course, I’m biased, as the bulk of my income now comes from self-publishing.

Not sure why you reduced my point to “Big Publishing.” I’m assuming you’ve submitted work to literary journals with cutthroat acceptance rates. Reputable/well-run small presses also reject most of what they receive. Most serious writers target publications and presses that have standards, which means those publications and presses do a lot more rejecting than accepting. The assumption is that the editors are putting together an issue or book that will consist of quality work, essentially working as qualified middlemen for readers.

Ah, well yes, small presses are different in that, while they’d certainly like to make a profit, they’re definitely in it more for the aesthetic nature of literature, so I agree with you there.

I understand your concerns with Big Publishing, too, though I stick by my larger gatekeeping comment: literature is unique in the sense that something other than the work itself usually needs to convince readers to read. That’s where editors and publishers come in. It’s not like music where an artist can give away a few free songs that can be listened to in ten minutes. Literature needs to be vouched for in ways that other art forms don’t.

Why does no one write about the evolution of publishing? There are at least two articles a day about the industry’s demise and they get reprinted over and over, Huff Post, the Rumpus, Indie Book Blogs, etc.

Did the manuscript illuminating monks picket Gutenberg?

Publishing will survive — in some form or another — as long as people are willing to spend money to read what someone else has written. I think that’s going to be a really long time.

If only you could download lattes…

Good points, though. It’s not exclusive to books; average people just don’t value art as much as the industries might like, which is partially due to conditioning towards cheaper goods by the retailers. Thanks to big boxes, stuff is cheaper to purchase and that’s a fact, even if it’s no cheaper to produce. I mean you can get a DVD for less than a movie ticket, an 800pg e-book for less than a print mag, on and on.

If a latte took several hours of sustained concentration to consume, you’d think twice before buying one.

I’m sorry, but Swartwood is wrong. Art isn’t worth money unless people want to spend money on it. If your book sucks, no, I’m not going to buy it for 4.99, or 1.99 and I’d even be hesitant to take it if it was free.

If you spend $6 on coffee, it’s because it tastes good, not because you appreciate the idea of “supporting coffee”.

It’s not price, it’s quality.

http://tinyurl.com/8b5k9l3 .

I think saying “Big Publishing is in it for the money” is laughable. Compared to most industries, there’s no money there at all.