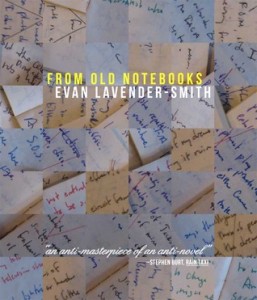

From Old Notebooks

From Old Notebooks

by Evan Lavender-Smith

Dzanc Books, December 2012

182 pages / $15 Buy from Dzanc Books

Martin Heidegger posited the idea that all criticism is existential and there is no impartial analysis outside of the experience of the reader. A reviewer of Evan Lavender-Smith’s From Old Notebooks asks: “Should the reader of F.O.N. expect the meaning or truth of the book to lie with its author? Does the truth/meaning of the book lie outside the book?” Furthermore: “There may be some question as to F.O.N.’s status as fiction, poetry, philosophy, nonfiction, etc. but hopefully there will be no question about its status as a book.” Both comments are from Evan Lavender-Smith critiquing his own book within the pages of From Old Notebooks, even revealing: “Why am I so averse to the idea of classifying F.O.N. as poetry? – Because poetry doesn’t sell.” That’s the way From Old Notebooks rolls, defying genre and classification, even defying the traditional boundaries of author and reader. On the exterior, it reads like a notebook filled with philosophical musings, hermeneutics, the germs of story ideas, dialectical exposition, hagiographies on dubious beliefs, aphorisms made ironic by their sincerity, and letters to death. But the flow of the notebooks is deceptively simple, appearing like a random collection of ideas when it’s in fact a journey through the Penrose stairs of Smith’s mind.

I came across From Old Notebooks several years ago when it was first published by BlazeVOX. F.O.N. was one of the first postmodern/experimental works I’d read. Since then, I’ve read a lot more experimental works, some of my recent favorites including Robert Kloss’s The Alligators of Abraham; One by Blake Butler, Vanessa Place, and Chris Higgs; and Janice Lee’s Daughter. With F.O.N. recently reissued by Dzanc Books, I was excited about diving back in. It’s hard to analyze experimental works because the experience the reader has is so subjective and without making assumptions about the author’s intent, a huge part of the critique, for me, comes down to how the work resonates on a personal level. Explorations of infinity and thought stripped away from form involve literary techniques that are invented along the path of creation, and as a result, often defy formulaic definition. That is what makes these works so bold and compelling. Part of the allure of From Old Notebooks, then, is its accessibility.

The subject matter and the themes vary, encompassing everything from film quirks to quandaries on death, musings on poetry, and pornographic abstinence. The notes incorporate personal whimsies, fears, and even worries about family. Rather than obfuscate, we have a movement toward revelation. But the investigation branches into even more questions and there’s a playfulness in the tone that engenders the feeling of a contemporized Socratic enquiry, only with oneself. As a few examples:

“God endowed the universe with an infinite number of signs, but only one fact.”

“Qualifying death as “unknowable” is, finally, an act of cowardice; death as “unknowable” preserves mystery, the possibility of mystery. The truth atheist knows death intimately; for him, there is nothing at all mysterious about death.”

“Perhaps they would be more palatable if independent films had more explosions in them.”

“Should I be concerned about exploiting my children by including them in F.O.N.?”

“Consciousness is my worst habit.”

Fascination is a trait that shines through the notes and his willingness to poke fun at his own work points not just to the characteristics of metafiction, but his own approach to ontology and metaphysics. That is, with a self-consciousness that regards epistemology as slapstick comedy and death as punch line to a bad joke. Unfortunately, the bad joke is existence and when Smith describes one of his wishes for F.O.N., he states, “that in its more serious moments it would provide great humor to an extraterrestrial race of beings, and in its humorous moments, great sadness.” The dichotomy of the emotions causes them to blend in extremes and points to the limitations of traditional fiction dealing with a fractured reality. Limitations are something Smith is painfully aware of, though the scope of his knowledge is extensive as he deals just as comfortably with Heidegger and Ulysses as he does Michael Bay and Megadeath. Pop culture and Shakespeare merge in a hybridization that deftly dialogues with the absurd and points to Evan-Lavender Smith as reviewer who is reader who is also the writer. “We are at once the animals being dissected and the scientists performing the dissection.”

From Old Notebooks encourages interactivity and self-questioning. If I could think of an analogous project, (as different as they are) I think of a game called Warioware which is as close to experimentally interactive art as games can become. Short segments from various games pop up for a few seconds and then jump to the next section, most of the mini-games lasting a few seconds. What makes the game so much fun is that it draws from all the various corners of the history of gaming. It takes a erudite architect to design a game that’s both a throwback to other games while crafting its own distinctive identity. In the same way, if a less skilled writer had undertaken this book, it could have easily crumpled into random vagaries that go nowhere. Fortunately, tempo and diction are masterfully navigated by Smith to make the reading experience a sublime one that never feels disjointed or chaotic.

This is not a somber work like Dostoyevsky’s Notes From the Underground with its depressing introduction: “I am a sick man… I am an angry man. I am an unattractive man. I think there is something wrong with my liver.” If F.O.N. takes inspiration from anyone, it’s Nietzsche, who also provides the opening quote of F.O.N. and wrote some of the most brilliant epigrams and aphorisms in works like Beyond Good and Evil and The Gay Science. There, he not only celebrated life and philosophy, but tore it apart and smashed it to pieces. In F.O.N., we get a little less smashing, but a whole new set of insights to the march of a celebratory romp that basks in life and its conundrums.

“Short story about a church on the ocean floor. Congregation in scuba gear,” is how the book opens up. On one hand, it’s an interesting idea for a short story. But considering its placement at the very beginning of the Notebook, the implication is that the classical sermon has been given a completely new context as is the reader who must re-contextualize and prepare for the new environment constructed by the book. “The highest compliment a philosopher could receive from a reader of his book: ‘I used to feel that way, too,’” Evan Lavender Smith states. Putting on my literary goggles and prose wet suit, I feel on almost every page that I am reiterating that very feeling, only shedding the past tense and saying: I still feel that way…

***

Tags: dzanc books, evan lavender smith, from old notebooks, Peter Tieryas Liu

I think FON is the dude equivalent of Bluets by Maggie Nelson, or The Balloonists by Eula Biss. (not a lot of dudes write in this style; aphoristic, personal, non-fiction, lyric)

I don’t think this is experimental because I don’t know if the book has a goal beyond being a book. His book Avatar, now that is an experiment…

I hadn’t heard of Avatar but will put that on my reading list. Thanks!

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/reviews/105871/ […]

[…] Higgs, I wanted to revisit The Complete Works of Marvin K. Mooney by Higgs. MKM, along with Evan Lavender Smith’s From Old Notebooks, was my first introduction to experimental works, and both are incredibly fun and challenging reads. […]