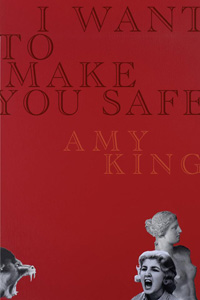

I Want to Make You Safe

I Want to Make You Safe

by Amy King

Litmus Press, 2011

87 pages / $15 Buy from SPD Books

Amy King is doing God’s work. Of course, I don’t mean God in a traditional Christian way; I mean God in the way that King speaks of God in her recent book, I Want to Make You Safe:

of our collective minds

of our collective wing wax

of our flights past time zones.

King’s poetry—its meandering syntaxis, its resistance to singular meanings, its mysterious connections and lack of connections—opens up the mind to unexplored avenues of thought. I also find King doing this work through her editing, specifically on the journal, Esque, which she co-edits with Ana Božičević, in which they bring together a wide array of contemporary poets and prose experimentalists, people like Jennifer Karmin, Cara Benson, Cynthia Arrieu King, Ching-In Chen and more. The new edition alone should get her a seat in heaven. If you haven’t seen the third issue, called Revolutionesque, you should definitely check it out.

What motivates this work in her poetry and in her curating? In an essay on queer poetry, King says, “Queer poetry strives to complicate the other, confound how we know that other, so that we might, however fleetingly, explore the other towards an even greater effort: to imagine What Else beyond this other self.” Imagination and complication and confusion as a goal for poetry. There’s an explicitly hopeful sense in King’s work: the hope that through a practice of imagination and effort to explore, we might find something outside of ourselves.

Amy King’s poems put the edge back; they back-pedal from safety or lighten the heavy, promise-laden clouds. If the clouds look heavy with rain, King launches a rocket into the clouds to seed them and bring that damn rain down already. I found a lustrous core of good old-fashioned queer hurt and joy. I know I’m projecting my own feelings on these poems. But no apologies. Like King said in an interview on HMTLGiant with Roxane Gay, “The reader makes “sense” of what she encounters using her own experiences and ideas. So a lot of poetry is associational.” Associate away!

A few days ago, I stumbled across the new “Hood” video by Perfume Genius:

The video gave me the feeling of what I imagined when I heard “I want to make you safe:” Arpad Miklos, this huge muscular gay porn star, swaddling Mike Hadreas: taking care of him, holding him, brushing his hair, putting make-up around his eyes. It’s tender and sweet and the radical opposite of bullying. Here’s one case where it does get better, Mr. Savage. This strong man, a man famous for his voracious fucking of other huge men, delicately handles, pets and cradles this twink.

And I went to the title poem of Amy King’s book and I projected all of these feelings onto it. How could I not? For me, queerness is born out of that tender feeling of being cared for, a gentle enclosure to seal one off from a harsh and angry world. It’s not only a theoretical construct, it’s an image from a dream. Or maybe that feeling I am describing is love. In King’s book, there is love, a lot of thinking about love. The promise of love between people.

This brings us to the last line of the title poem in the book: “Please reattach the orifice if / I’m ever to hold your love.”

Why was the orifice detached in the first place? Who did the detaching? It makes me think of that classic gay erotica story called Blue Light by Aaron Travis. In that story, gay sex goes supernatural as a dominant top literally divides the body of his sub into various pieces and procedes to use those body parts in lustful and lascivious ways. The sub is all the while alive and conscious of what is going on, enjoying his body’s division and manipulation:

I felt myself being lifted up—a sensation of weightlessness and vertigo—the room fell and whirled around me. I tried to scream with horror, and couldn’t. I caught a glimpse of something in the mirrors—my body, stick-still within the blue light field—Michael standing aside—holding something in his hands—holding—my head—

Ah, the m-dash has never been used to greater effect. At the end of the story, the sub’s body is magically returned to its original state. All orifices are reattached and the feeling is one of intense satisfaction, fullness. It gives a twisted meaning to King’s line: “Please reattach the orifice if / I’m ever to hold your love.” King’s words orient the reader toward the gaps, the breakage, desire:

another time

to ache by,

the jester jumping

along our spinal

cords between

knuckle bones—

the imprint of God’s

shattered fist.

As I was reading King’s book, I ended up thinking of a love triangle—between two people and King’s God. This God or god is a different kind of being, one closer and less distanced from the strangeness of daily life.

I really loved the two long poems in the book, “I Want to Make You Safe” and “This Opera of Peace.” I found both to be slow unfurlings of her ideas and her imagery, her meandering thinking-in-writing about intimacy and love and connection and language and nature and objects: “I will marry you and take / You to crucify continents.” The breadth of King’s imagery is shocking at times: “beer into poetry,” “political drudge into words of oil on skin,” “a baby wren beneath my tongue.” The images are gorgeous, obviously. In the shorter poems, this imagery was so dense, so baroque, so maximalist that at times it feels constrained, bucking to get out. In the longer poems, the dense imagery has more room to breathe.

At the end of King’s essay on queer poetics, she reprints a poem, “Men by the Lips of Women,” that she says illustrates her own poetics in action. The poem is included in her new book. It begins: “I’m in love with a man who doesn’t love me.” Who is this queer woman writer who loves this man? Are we, queers, okay with this hetero love? Or is cross-gender love always hetero? Clearly no. And who is this “man who doesn’t love” her? It’s a periled start to this queer poem, it’s destabilizing and off-putting on some level. Uncomfortable. The line “His fright is an orb of Hold me, I’m yours” takes me right back to Perfume Genius and Arpad Miklos, but now the feeling is more complicated, riven with instability and inpredicatability, unmoored from easy imagery. We’re thinking about where the woman poet fits in. But then who I am to gender Amy King? Or to make any assumptions about relations, sexual or gendered or otherwise? The poem reminds us to look warily, askance, to linger. And yes, in that lingering, that splicing, there is a utopian desire. Surely, the What Else points toward a different future. As the poem stunningly concludes:

and my gender is powerless in this. We are metered only by our own machines,

while the book is a clock that forgets her mechanics.

Her hands can count but would rather wipe warm dew,

the pall from your lips and kiss the lids

of your eyes from sleep. Here am I, is he,

with yoke and shadow removed, she is, her in me,

apart from you, man reading men by the lips of women.

As readers, we’ve moved into a love in which gender has lost all power. There is a slippage in the voice of the speaker, as the “I” becomes “he” becomes “she” and then “her” and then “me” and finally “you.” Subject becomes object becomes subject and object and “sobject” continually and repeatedly spinning back around. It’s a happy kind of instability, one which I (or he or she or you or this “man reading”) am happy to live in for a while.

***

John Pluecker is a writer, interpreter, educator and translator. His work is informed by experimental poetics, radical aesthetics and cross-border cultural production and has appeared in journals and magazines in the U.S. and Mexico, including the Rio Grande Review, Versal, Asymptote, Picnic, Third Text, Animal Shelter, HTMLGiant and Literal. He has published more than five books in translation from the Spanish, including essays by a leading Mexican feminist, short stories from Ciudad Juárez and a police detective novel. There are two chapbooks of his work, Routes into Texas (DIY, 2010) and Undone (Dusie Kollektiv, 2011). A third chapbook, Killing Current, will be published by Mouthfeel Press in 2012.

Tags: amy king, I Want to Make you safe, John Pluecker

[…] I Want to Make You Safe by Amy King, a review Share this:ShareTwitterFacebookDiggRedditStumbleUponEmailPrintLike this:LikeBe the first to like this post. […]

Maybe that “man who doesn’t love me” is a “man” other than biologically.

All sex is “hetero”.

(Je est un autre. Even masturbation is, self-ishly, “hetero”.)

All gender is “cross-gender”.

For me, the problem isn’t judgement (or even “assumption”). Rather than a privilege or a right, judgement is an always already, a perspective on perspective itself.

The problem – with gender understanding/construction, with every human thing – is following one’s own rules.

This blogicle makes King’s poetry sound very good; I enjoyed reading this blogicle.

–uh-oh . . .

The e-mail notice said: “I hope you’re already enjoying the holidays! As always, our judges,

Wendy Babiak, Tara McDaniel and Ruth Bavetta, have selected six

finalists from this month’s group [see links at the bottom of this

email]”

Instead, the link leads to yet another self-advertisement for Amy King’s gibberish!

[…] for Her Circle. March 1, 2012. • Creepy Valentine on Poets & Writers. February 14, 2012 • John Pluecker for HTML Giant review. February 2012 • Sara Jane Stoner and Julia Heim read. February 2012 • VerseDaily […]