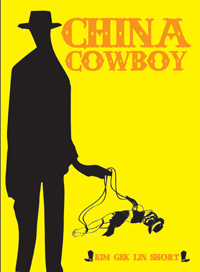

China Cowboy

China Cowboy

by Kim Gek Lin Short

Tarpaulin Sky Press, June 2012

132 pages / $14 Buy from Tarpaulin Sky

I read China Cowboy under the most perfect of circumstances: in a garden a few hundred feet from the Pacific Ocean, perched on the Ring of Fire that fuses San Francisco to Hong Kong. The voices of Chinese daytime television descended from my neighbor’s second floor window onto the pages of the safety-yellow book, which had arrived via USPS in a rough condition apropos of its protagonist. Like the abused and well-traveled La La of Kim Gek Lin Short’s second full-length collection, the bubble mailer was practically clawed open, the book so scuffed that its soft outer layer was worn to the quick, almost see-through.

The ocean echoed the book’s evocative opening line: “A bluegrass of fogging.” And the last place I’d been before here was Nashville, where any nobody can twang out a couple tunes at an open mic and even the weak-stomached can’t turn down a shot of 35-year-old well whiskey from a commemorative porcelain decanter in the shape of Elvis’ head, forged on the occasion of his majesty’s death in 1977—also the year of La La’s birth (“Y’all, I would’ve been out of your league at 12. I’m only tattlin’ now, cause I would’ve been 20 today,” she boasts from an eternally-pubescent afterlife hellishly specified as 1997).

It’s with such brash spunkiness that La La—a poor kid in Hong Kong with aspirations of American country singer celebrity—tells the story of her brief life and violent death, including the glamour she imagines for herself, the many small deaths along the way and her songwriting star that keeps ascending from beyond the grave.

A ring of hellfire encompasses La La from the moment of her birth, when the devil himself (“a white dark man”) wraps a searing-hot hand around the breech fetus’ calf and delivers her into the harsh world of Kowloon, 1977. La La’s parents make their living “taking the tourists to an alley stabbing them stealing their stuff,” and the child is used as a prop to gain victims’ trust. Early on, to cover up the odd claw-shaped birthmark on La La’s leg, her mother dresses her in “cowboy boots tube socks,” and Patsy Clone is born: La La’s country star alter ego, her ticket to America, where children “have their own rooms.”

Unfortunately, one of her family’s victims is an American ex-con/soybean farmer/child abductor who sticks around Hong Kong following the assault, and one day La La never comes home from school. Maybe Ren, a.k.a. Bill, a.k.a. William O’Rennessey, is really the devil incarnate, or maybe he’s just one of the devil’s many agents on a confused, globalized earth circa 1989. He is certainly an updated (and actually American) Humbert Humbert whose version of the coveted nymphet is called a “la la” (with a lower-case L). China Cowboy’s heroine is just one of many la las in the world, an unlucky abductee who’s bribable by sugary cereal, plastic microphones and flouncy skirts. And Ren is a man who will do anything the voices tell him—assuming aliases, squirreling away la las in remote corners of the country, wrestling with his own delusions of grandeur and multiple personalities. In China Cowboy, “Hell is red carpeted stairs lined with plastic runners smell of wicked shit”—a particularly cheap and Americanized evil. Ren “goes all the way inside,” and La La never comes out—smuggled through the port of San Francisco, sequestered in a shoddy Missouri cabin, serially raped and, finally, poisoned.

If this all sounds too hideous to be enjoyable, I must point out that Short infuses the story with kitsch, humor and addictively playful language that balance out the heartbreak. The dark subject matter is made lighter by La La’s protective pantheon of American deities: “Loretta Lynn Patsy Cline Emmylou Harris beautiful cowgirls,” Clint Eastwood, Woody Guthrie. She complains: “In my sleep I am starring in Coal Miner’s Daughter. I am as convincing as Sissy Spacek except I am Chinese and just can’t help it. I can’t.”

An expanded version of Short’s chapbook Run (Rope-a-Dope, 2010), China Cowboy is a poetically-executed novella largely taking the form of prose poems, although other textual structures creep in toward the end of the book—including spacious, lineated blocks that stand in for visual artworks created by Ren’s artist doppelganger, and rhyming country song lyrics in “La La’s Guthriecrucian Songbook: A Bildungsroman.”

In Short’s often singsongy prosody, the blunt physicality of child rape and the simplicity of kid-speech melds with the ethereal and the eternal: “He tapes toilet roll to broken mouth retainer to hard semen-gauzy sock, it goes in my crotch,” but La La promises “in my new life I will be white heat, pure I will rise.” This is the language of dissociation, of self-immolation: “I will be swept ash, light I will rise.”

In the piece entitled “Run,” we see La La’s self-aware side, the part of her that suspects her “country superstar humility” won’t save her:

La La’s is a disembodied (yet entirely, painfully bodied) voice traveling across decades and continents, transgressing mortality to speak. She is a ghost inhabiting the dreams of her captor, her parents and herself. She sees herself dead, changed, transparent, famous, pregnant, American, flat-faced, blonde, in fugue, at a mic, triumphant. In an account of her final moments to her mother—one of the most difficult passages to read—La La notes that

The Lovely Bones this ain’t. China Cowboy is a satanically intricate narrative with seemingly infinite vantage points in space, time and sympathy. After all, Ren isn’t always evil and he’s not never the victim, as Short admits in her acknowledgments: “Boots up[…]to all the cowgirls and cowboys who sparked what’s good about these characters and to all the angels and devils who ignited what’s badder.” It is an account of trauma and the stories people tell themselves to survive, in the larger context of colonialism (1997 representing the British handover of Hong Kong) and cultural tensions between China and America: “When I picture home Ren doesn’t picture the same place. If I could do-over anything I would make Ren picture the same place.”

An incredibly original conceit that is so thoughtfully constructed, with so much attention to detail and such a range of source material—from Dante to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly—the book must be reread to catch all of Short’s utterly un-snarky cleverness. She’s a master at making her strange little pieces glow brighter under the perfect titles, which locate them in the complex web of personal myth and symbology that Ren and La La spin around one another: “Butcher Holler,” “This Bean is Your Bean,” “Repulse Bay,” “Cow Loon.” As China Cowboy progresses, its interior space deepens: a network of dreams, self-delusions and mini-universes reveals itself through Nabokovian footnotes, appendices, crime reports, fake nonprofits (Cowboys Against Child Abuse), press releases for suspicious art galleries that just gush “front.” But for what?

With this and all of her projects, Short has expanded and fused the poetic and narrative fields, creating a zone where elegance and grace can gambol with the just-plain-fucked-up. The book is disquieting, seductive, a preteen pathological liar busking on a deserted corner with an invisible guitar. Is it awful to suggest we can all take a cue from the La La school of stress reduction?: “I want to scream. But I don’t. I ask myself // what would Patsy Cline do?”

***

Sarah Heady is a recent emigrant from Bell Buckle, Tennessee, a founding member of the New Philadelphia Poets and an MFA student at San Francisco State University.

Tags: China Cowboy, Kim Gek Lin Short, Sarah Heady

Good straight up review! (I took a more twisted route http://jacobrussellsbarkingdog.blogspot.com/2012/05/review-china-cowboy.html).

Yes, I saw that and loved it!

ahhh kim gek lin, she is both intelligent, cunning, and beautiful. i guess that’s three things. i love her writing though. i can’t wait to get my hands on this cowboy.

tinyurl.com/7zjh3zc

[…] to Sarah Heady [read the review here], who not only had the guts to read the book in the first place but was also able to engage its […]

[…] more of the hybrid work I am used to seeing from Tarpaulin Sky, in books like Kim Gek Lin Short’s China Cowboy and Sarah Goldstein’s Fables. In fact, The Tales earned its publication by winning the 2012 NOS […]

[…] to Sarah Heady [read the review here], who not only had the guts to read the book in the first place but was also able to engage its […]