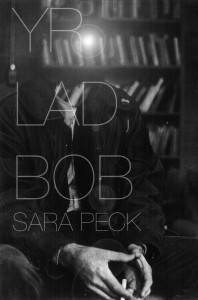

Yr Lad, Bob

Yr Lad, Bob

by Sara Peck

Persistent Editions, 2013

$8 Buy from Persistent Editions

The South Carolinian poet Sara Peck has opened, in part, her chapbook Yr Lad, Bob (Persistent Editions, 2013) with a set of phrases that reference two very different experiences of time:

waiting for the train // I’ll always love / you

Waiting, of course, tends to slow time down so much that one becomes aware, almost, of its not passing. And a variety of apprehensions can exacerbate this awareness even more: will the train ever come? Will I be on time when I get where I’m going? Will I be able to do whatever I’m going there for? The feelings waiting can trigger are then contrasted with the line’s next phrase, the promise of which, of always being loved, attempts to mollify all apprehension and impatience. That is, an awareness of how slow time can feel is opposed to a feeling or desire that love will trump time by not ending, which is implicit in the word “always.” Readers of Yr Lad, Bob will find out in the book’s Forward (by poet Lisa Fishman) that single and double slash marks in the text indentify line breaks and stanza divisions in original poems; Peck has culled lines and phrases for her own book from the works of Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, and Robert Duncan and interspersed these with what were once her reading notes. Here though, as elsewhere throughout Yr lad, Bob, the slash marks serve an additional function: they create silent interruptions which, surprisingly, and unlike commas and other punctuation, do not require the reader to stop or pause; in fact if anything they force the reader on. As a result, the reader accesses moments, phenomena, and feelings which are almost mutually exclusive but which can occur in the poems in one and the same line, or, in terms of the poem read aloud, in one and the same breath. The slash marks allow for the co-existence of things that don’t normally go together, and encountering and experiencing this co-existence is one of the many pleasing things that happens to readers of the book.

Elsewhere in Yr Lad, Bob the slashes touch on time by graphically disrupting colloquial phrases (such as “over and over”) that express repetition if not continuity:

that freshness, over / and over: summer / in the folds of your dress

In examples like these, one begins to see that part of the relineation project of the text is to re-score, or set to new music, a selection of lines by Black Mountain poets. The slashes, however, take us further: look at how they separate the line above into the very tresses or folds on which the line itself ends. It is in moments and places like this that Sara Peck’s chapbook expands the reader’s awareness of time to include an acute awareness of the overall appearance of the page. And such an acute awareness goes far beyond an understanding of reading which views that process solely in terms of signification, that is, in terms of words having the function of conveying something (mental pictures, emotion, information) to a reader or receiver.

As the poems in Yr Lad, Bob gradually shift us from reading to looking, we become, in places, exposed to the raw exchange of sameness and difference which is evidently a core part of language. Even a phrase as simple as

weather / to reassure

is teeming with variation. The first syllable in “reassure” picks up and recycles, as in a mirror reversal, the final syllable in “weather.” The same vowel combination (“ea”) appears in both words, but each time differently, once as diphthong, once as separate syllables. Finally, both words end in “r”-sounds which are close but not exact matches; the sounds cleave toward each other as they fail to overlap perfectly.

The awareness of time cultivated by the text, as well as the degree of attention it coaxes from readers, combine and take a surprising turn when Peck’s own voice enters via her notes to herself. This is because these notes are not simply observations about specific lines from other poets’ poems; they extend to the actual copies of the books she must have been using:

already written in my book: “quite a concept”

and

note in book: “very complicated syntax”

have several dramatic effects. One of these, again, is to show and reinforce the fact that Peck’s reading project isn’t exactly “about” Levertov, Duncan, and Creeley. Rather, books containing their poems have been one of her sources, perhaps the way Charles Olson says in his manifesto “Projective Verse” that the poet “will have several sources” for a “transfer of energy.” Secondly, such moments allow readers access to a kind of back-story, in that they conjure simple moments of reading from the author’s work on the text that has become Yr Lad, Bob. What must have been part of the process is now part of the product. Finally, Peck’s source books, used, borrowed, or perhaps stolen, record and preserve the trace marks of other, unknown readers, strangers to us but people who have nevertheless been here before. The cumulative effect is the addition of depth.

The notes, however, have a greater consequence for the experience of reading the book. As we come across and encounter these notes, we are basically watching Sara Peck read, except that this watching also happens through reading. So reading Yr Lad, Bob also means reading Sara Peck reading. Yes. And as we read over her shoulder, we become aware that we are doing the same thing she has been doing. That’s why we’re called the reader. The book draws attention to us, to what we are doing when we read it. But it does so while we are doing it, which is another way of saying that it makes us hyper-aware of, or tunes us in to, the moment, or if you like, the now. Yr Lad, Bob opens by referencing the experience of time in terms of waiting. Its relineation project, which relies on the use of the slash as non-interrupting punctuation, sharpens our attention to the language of the book as well as the whole appearance of the page. And this heightened awareness comes to include not time’s passing in general, but the immediate moment, which is more concisely stated in the book’s final line:

this this a regular happening

There are other surprises in Yr Lad, Bob but I want to close with only one of them. Near the end of the book we read

ash marks probably mine

which again opens the back-story: the author has been smoking (a cigarette or something that drops ash; my personal belief is that it was a cigar) but is somewhat uncertain whether the traces are hers or (perhaps) from the unknown earlier reader. In a book that listens as closely to what is said as it does to what is not said, it is difficult not to turn “ash marks” into “slash marks.” Indulging this reading (if the slash marks are “probably” hers, they are, just maybe, possibly not hers) raises questions about ownership and authorship, given the importance the slashes have for the project. Let me say only that the uncertainty about who has done what only serves to release Yr Lad, Bob into the world, and into language, with a kind of freedom denied to most works. To read it is to feel it open, and open.

***

Eugene Sampson‘s poems, reviews, and translations from the German have appeared sporadically online and in print.

Tags: Eugene Sampson, Persistent Editions, Sara Peck, Yr Lad Bob