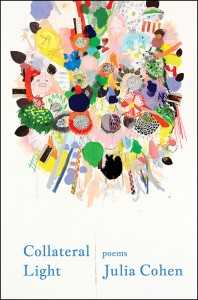

Collateral Light

Collateral Light

by Julia Cohen

Brooklyn Arts Press, Oct 2013

94 pages / $15.95 Buy from BAP or SPD

On the first page of “No One Told Me I Was the Arrow”, Julia Cohen writes:

a life

of sea-

sickness

dreaming of ships

An insect

on snow

At the limit

of our

body

a brief spasm

of laurels

Caught, sickness, limit, spasm. No one told her. In this, the first poem in Collateral Light‘s first section, Cohen seems to be setting forth an aesthetic program both in her subject matter and in the laconic precision of her style: To move over the frozen terrain of an aestheticized life, practicing an insect-like lightness and thereby avoiding falling into the ‘snow’. This is not, in itself, an unadmirable pursuit. It is also one to which poetry is particularly well-adapted–is there any medium more capable of lambently exploring ‘the limit/of our/body’ without becoming mired? And yet perhaps I can be forgiven that my heart dipped in my chest at the prospect of another book devoted to elegies on the subject of inability and asymptotes. It therefore came as both a surprise and a relief when Cohen discards her regretful tone at the poem’s conclusion:

my point

plunge

into a glass

of soil

“An insect/on snow” nothing, O me of little faith. Cohen is ready and able to dive within. In Collateral Light, we have the pleasure of going with her.

Over course of the poems following this introduction, Cohen delivers on the promise vested in the conclusion of “No One Told Me I Was The Arrow”. Her writing revolves around shifts, mutations, permanence, lability. Certain terms recur with such regularity that they become fraught, even overloaded, with meaning. Arrows (those symbols of both indication and entry) appear again and again, both negatively (“My pixels/deflect arrows”) and positively (“I’m filled/with invisible arrows”). Coats, husks and shells are shedded or pierced, disrupting the boundaries between the within and without of a given person (as when she writes, “Kiss my puppy lips my deer lips/the animal inside that animal/alive & yelping through the skin”). The introduction or relaxation of this confusion is at the center of many of Cohen’s more arresting passages, such as in the eponymous poem’s opening lines:

inside your face

& look down

at the sunken garden

My toes are cute

My packet of

bees comes in

Spreading whiteness, imperfect memory, gardens (be they sunken, frozen, night-, or made up of “Fake flowers burst forth from fake seeds”), ice, frost, veins, circulation and filtration. The throughlines multiply without compromising the slow, considered style. Cohen knows how to play to the strengths of that style; this is perhaps best-displayed by the particularly wonderful “The Decoy Museum Is Still”, in which sparse lines such as, “You walk into a stranger’s dirty pocket of air,” seize attention through their quiet profundity.

Cohen deserves to be lauded for what she is doing, but it’s nonetheless worth noting what she avoids doing. Her poems are both active and interactive, and yet possess none of the common signifiers that contemporary readers might associate with such terms. The rhythm is not argot-conversational or rat-a-tat percussive; the verses are not fit to bursting with pop-culture bricolage; there is no compulsive disgorging of confessional factoids. Cohen engages the reader through the steady application of precise language, carefully maintained across the length of each individual work. She never abandons her mode in favor of spasmodically gesturing beyond the limits of comprehensibility. If it seems like I’m belaboring the point, here, it’s because it’s a point that could stand a little belaboring: In a time when contemporary poetry is frequently (and unfairly) pigeonholed as belonging to either a hermetically classicistic tradition or a hypermodern, glossolalic movement, Cohen does not allow herself to be lumped in with either.

What is perhaps most admirable about Cohen’s sparsity is the different ends to which she applies it without ever breaking form (and thereby introducing discontinuities into the flow of her poems). In one line, she’s deploying remarkably piercing statements that are not diminished by their condensation, such as, “The warmest part of a name is the body/breaking away from its name,” or, “The decoy museum is still a real museum/so distracting you can die inside & not/even know it.” Then, as soon as the next line, she’s warmly tragicomic (“I can’t just sit here with feelings”, or, “Okay so I don’t want a sad/painting watching over us”). The friction between these different frequencies keeps her poetics lively, present, where they might otherwise become impeded by their responsibility toward incisive accuracy. At times, the rapidity and deftness with which she produces this friction is so well-executed as to produce a chord rather than competing melodies. The simplest instance of this is in a single line from the long poem “I Stared at Your Camera & Promptly Died”: “Death is the opposite of dying slowly balloon balloon”. One of the more complex is in the multi-part coda, “Practice by Fire & Doubt”:

throne & success of merchants

Down falls the casket like a white bird

I’m so buff

I’m a petite freak, a veil of

living green sprung from

the poetics of doubt

The conflicting registers present in lines like these produce a feeling of being spoken to rather than being spoken at. It allows the poem/poet to remain personal without having to neurotically imperialize the poet-as-person’s anxieties.

That consistent personality is responsible for much of the enjoyment to be found in this collection. “Personality” in poetry (hell, in writing on the whole) is all-too-often conflated with those stylistic tics and belletrisms that are lumped together under the umbrella of “voice”, as though the presence of a writer is communicated solely through curated deviations from a neutral ‘non-style’. Thankfully, that is not the “personality” I am speaking of here. What I am referring to is the feeling of constant interpersonal participation in Collateral Light, derived less from an intrapoetic self-branding and more from the milieu these poems create. Cohen repeatedly traverses the space between herself and the reader: She poses questions (“Do you consider yourself vertical?”), puts her face/inside my face, retreats within her own body for lines at a time only to sally forth and entreat the reader, “Turn your inside voice out/words flailing then body-anchored.” She sharpens her point, and we watch; she plunges, and we plunge.

***

Gil Lawson is a writer from Santa Fe, NM. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in such places as n+1, The Hypocrite Reader, ditch, and a series of chapbooks from Two-Suitor Press. He currently lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Tags: Brooklyn arts press, Collateral Light, Gil Lawson, julia cohen