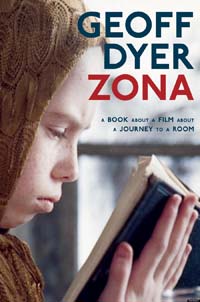

Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

by Geoff Dyer

Pantheon, February 2012

240 pages / $24 Buy from Amazon

Film is a visual medium. Images tell the story and words are subservient to those moving pictures, but in many of today’s feature films, words cart the story around like a hospital attendant. Dialogue has more feeling than images and cinematography steps aside, less emboldened to take our eyes from the star power or a crucial plot point. Still, they are an everlasting semi-bounty of filmmakers whose images speak their consciousness: Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Stan Brackage, Stanley Kubrick, David Lynch, and certainly Andrei Tarkvosky. To write about Tarkovsky or any other master is a tall task—the visual medium is not a daguerreotype of the sentence, though we use sentences to describe images that affect us. Famed film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum has said Chris Marker’s 55-minute film, A Day in the Life of Andre Arsenevich (a medley of Tarkovsky’s images with documentary footage of him shooting his final film The Sacrifice and on his deathbed) “is the single best piece of Tarkovsky criticism I know of.”

Geoff Dyer’s new book Zona (it’s also the Russian title of Tarkovsky’s 1979 picture about three men—the Stalker [the guide], the Writer and the Professor—who journey to the mysterious Zona [Zone—a place cordoned off by the military], to find The Room—a place where all wishes come true) is a work both featureless and frustrating, containing a powerful twenty-page swath—maybe “The Room” of the book—but surrounded by a patented solipsistic voice more reminding of a young blogger’s self-satisfied, mortally reductive voice.

Heavily peppered around the scene by scene recap of the film are Dyer’s digressions. Some relate to Tarkovsky, the production of the film, and both the political and personal in the Russian state at the time and how it gave birth to such artistry. Yet a number of them are soi-distant, including a long riff on the resemblance of Dyer’s wife to George Clooney’s co-star in the Steven Soderberg version of Solaris, Dyer’s experiences with drugs, as well as his wishes to have bought cheap London real estate years ago and have that delicious three-way with two other women he so desperately pined after but never achieved. The latter wishes are germane to a film containing a room where all one’s wishes can come true but I would argue “trying to fathom out what [Dyer’s] deepest desire might be” (172) is better left unsaid—perhaps that is why the Writer and the Professor’s desires are not revealed in the film and why they can’t enter the room when they finally come to the threshold. These particular digressions seem more revealing about how the ego yearns to be gratified but Dyer’s feels quite sated. That he uses type to spell out every writer’s dream, “I should say what it is that I most want from…this book…easy: success,” is surprisingly uncouth. The groveling seems uncalled for, least of all because of his privileged position in arts and letters.

What is further disjunctive when paired with Tarkovsky’s great vision of striving to find meaning in the world (Writer states we are here to create beautiful things) is Dyer’s often using language in a lazy, staid manner. The sentences are palsied, as here when he again goes on about his self-worth:

What is further disjunctive when paired with Tarkovsky’s great vision of striving to find meaning in the world (Writer states we are here to create beautiful things) is Dyer’s often using language in a lazy, staid manner. The sentences are palsied, as here when he again goes on about his self-worth:

This chatter or self-talk may be ameliorative as a facebook status update, but the modern-day neurosis of self-love is anathema to the subject of the book—the film. If one writes a love letter to a great artist shouldn’t all contained in that letter be beautiful? Tarkovsky delivered a film with images and sound that will last forever and except for a lucid section on The Zone, Dyer’s dappled prose loses power when trying to limn what percolates in his consciousness.

That previously mentioned section of the book does prove very enjoyable and informative. From pages 73-95, Dyer’s digressions hit a sweet spot as he says: “One of the big unanswerable: what is the Zone like when there is no one here to witness it, to bring it to life, to consciousness?” and “One of Tarkovsky’s strengths as an artist is the amount of space he leaves for doubt,” and that “the chief characteristic of the universe” for Tarkovsky “is an almost infinite capacity to generate doubt and uncertainty (and, extrapolating from there, wonder.” (90-1) These broad strokes of concrete criticism breath substance into his enterprise, but Dyer quickly falls back into more personal trivia that drives the reader to ride roughshod.

Aside from this section, Zona is more a self-help book for Dyer to work out his demons, rather than a tribute to Tarkovsky or his film. There can be a beauty made of giving one’s self a biopsy in the face of art. Rilke did it in The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, but he chose a failed poet as his canvas and wrote sentences of grand stature. Early in his career, Jean-Luc Godard prided himself on taking subpar books and stories and making movies out of them. With Zona, Tarkovsky made a mountain that isn’t going to be degenerating anytime soon. Beside it, Dyer’s Zona comes off as a cheap plastic trinket.

***

Greg Gerke‘s fiction and non-fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Tin House, The Kenyon Review Online, Denver Quarterly, Quarterly West, Mississippi Review, The Review of Contemporary Fiction and others.

Tags: geoff dyer, greg gerke, stalker, tarkovsky, Zona

i also didn’t like when he said no one sleeps in a sweater. i sleep in a sweater. dyer knows nothing!

every review I’ve seen of this book doesn’t mention the Strugatsky brothers’ novel (published in English as “Roadside Picnic”)— does Dyer write about it and its relation to the film?

Not that such a thing would be ‘for’ or ‘against’ his prose, but you make it sound like Dyer is (self-)consciously standing at the threshold to The Room in the writing of this book.