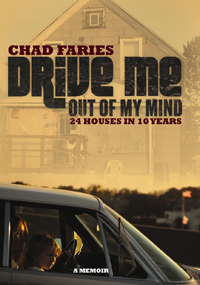

Drive Me Out of My Mind: 24 Houses in 10 Years

Drive Me Out of My Mind: 24 Houses in 10 Years

by Chad Faries

Emergency Press, 2011

280 pages / $16 Buy from Amazon

In his 1958 book, The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard writes, “if we want to go beyond history, or even, while remaining in history, detain from our own history the always too contingent history of the persons who have encumbered it, we realize that the calendars of our lives can only be established in its imagery.” The Poetics of Space describes a philosophy of poetic Imagism (precision of imagination) coupled with, in part, a phenomenology of the home as (not just) mortar, 2×4, and stone. In my reading of Bachelard, our histories are only as real as the Images that embody them.

I was reminded of The Poetics of Space when I read Chad Faries’ memoir, Drive Me Out of My Mind: 24 Houses in 10 Years. The book is separated into a chapter-per-house-lived-in, each chapter begins with a street-and-town, a year, and some song lyrics—a soundtrack to the book that almost acts as white noise on which we can focus when the screaming and partying in the foreground get too depressing. Each chapter ends with “and then we moved.” The book begins at Faries’ birth in 1971 and moves its readers through a difficult–sometimes funny, sometimes grotesque–landscape of pick-up-and-go with his drug-booze-and-sex addicted mother, her family of women, and a wild cast of male characters, to 1981. Drive Me is not only scaffolded by the houses the author lived in before he hit puberty, but Faries’ houses exist in a space created by the coupling of memory and imagination in order to forge the memoired homestead. “Our whole house,” Faries writes early on, “was made of the shadows of others, and we sucked that gray light into our guts to push the total darkness away and claim everything as our own.”

To Bachelard, the shelter—in whatever form it takes—is the place through which we’re allowed to experience the world. The daydreamer (reminiscer?), Bachelard writes, “experiences the house[s] in its reality and its virtuality, by means of thoughts and dreams.” Faries’ recollections are many times dreamlike sequences—like the ascension of a Ford Falcon into a Florida sky—fostered by both reality and the speaker’s desire to escape it. The memoir takes its reader on a journey from house to house, sure, but these houses are many times just faulty shelters for the fucked up events that happen inside and outside of them.

To be sure, Drive Me is a book made up of memory-images and their underbellies like the car he rides in to Florida that flies up to heaven to meet its erstwhile owner or the chapter in the voice of a lost hamster circling a house backwards in order to rewind time and save Chad and his mother. In another scene, parked on a roadside in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (where Chad spent most of his early years) in a Ford Galaxy, Chad’s mom and her boyfriend screw in the front seat, while Chad, in the back seat, imagines another scene altogether—instead of being forced to watch, he gets a choice:

Mother and I had our eyes on one of the spruces. She caught a glimpse of it out the side mirror as she tilted her head and held a breast in her hand, feeding it to Jensen. The tree was haloed behind an old rusty barrel like a fat angel in a faded church painting. There was a spaceship too, helping out with a spotlight, and some planets. The snow began to fall, but it wasn’t cold a bit. Mother peeked her head in the back seat.

“Would you rather watch this movie or get the hell out of here and snap the trunk of that tree so we can bring it home with us?”

And off they go into the woods arm in arm, leaving Jensen a cardboard cutout in the old Ford Galaxy. Scenes like this imbue Drive Me with a specialness that’s only born through the coupling of memory and imagination. A revision, so to speak, of experience-as-fact. The fact is that no story exists without both, and Faries’ story can’t exist without imagining a way out of it. But Faries’ narrative takes an interesting turn toward the back half of the book. What once was magic in the eyes of a child (as sordid as the accumulation of lots of drugs, lots of sex, and lots of fucked up grown-ups may have been) grows less and less glittering. Chad becomes more worried about being abandoned by his mother. He locks away the invisible Green Lantern ring that has gotten him through many a rotten moment. As he gets older, though still a small child, his world starts looking just a little more bleak.

One of the most affecting scenes in the book exists in that back half when, on a walk through a cemetery with his friend/older sister figure, Suzanne, they happen upon two of Chad’s neighborhood buddies, one of whom, LittleMan, has recently taught Chad to use the word cunt with abandon. The two other boys wrestle Suzanne to the ground—the scene is graphic and awful, and the shock of it freezes Chad in a sea of contemplation until he summons his old superhero courage just long enough to yell, “Stop,” which does nothing except alert a neighbor who shoos them all away. No fanfare, no punishment. In this moment, Faries writes, “I realized I didn’t know what world I belonged to.” As Suzanne is fondled and humiliated—raped—the boy Chad speaks (squeaks?) out against the cards he’s been dealt. For my money, here’s the crux of the narrative, a crisis of faith.

I don’t actually have much sympathy for Mother as Faries portrays her—though I’m reminded occasionally that she loves her kid and that her kid loves her—but I do know the stronghold grip of Mother, how she tugs at your heartstrings, how she amazes then betrays you. And you, her. And I’m not sure this is a perfect memoir (what is that?); sometimes the houses themselves seem to buffet the book from its own greatness—but there are enough tatters and missteps painting Faries’ early years that maybe the circle can’t be closed gently, neatly. The strands won’t weave together into that perfect childhood home Bachelard imbues with “all the positive values of protection.” At one point, Faries recalls, “I was convinced I could live without Mother and didn’t need shit from adults anymore. Staring at the other house across the street, I remembered that the adults weren’t any different than boys and girls,” highlighting the messiness of discovery and assimilation of memory into adulthood.

Drive Me’s last chapter is in the form of a transcription of an adult conversation between Chad, his mother, some aunts, and a family friend. While one aunt tattoos the name of a woman—a lover whose ghost haunts the entire book—on Chad’s back, the women recount their versions of history, and his mother points out, “Well, I have memories too that are wrong.” In the end, calling all memory into question, the group waits frozen in time for a nonexistent phone to ring in the tattoo parlor. No tidy conclusions here.

Back at a rooftop birthday party circa 1974, toddler Chad—stoned because someone gave him a hit of a joint—watches his mother from a roof rail-cum-cloud vantage, “An omnipotent mother was puffing a cigarette, her breath a braid of smoke,” perhaps an allusion to the infinite poetics of space, that great amalgamation of memory and imagination, certainly recalling Charles Simic:

She bore me swaddled over the burning cities.

The sky was a vast and windy place for a child to play.

For Simic the world doesn’t end, even after his flight over destruction. For Faries, beyond the music and mayhem, “after our bellies were full we all reveled in being lost, mistaking it for peace.” There’s some freedom in that, huh. Getting lost in the sky and making that your jungle gym.

Tags: Alexis Orgera, Chad Faries, Drive Me Out of My Mind: 24 Houses in 10 Years

Addendum: You can get the Kindle version of this book for free until tomorrow: http://www.amazon.com/Drive-Me-Out-Mind-ebook/dp/B0055T3EEK/ref=tmm_kin_title_0?ie=UTF8&m=AG56TWVU5XWC2&qid=1323836379&sr=8-1

You can also view a trailer at http://www.chadfaries.com