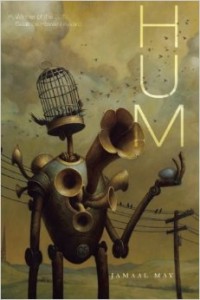

Hum

Hum

by Jamaal May

Alice James Books, Nov 2013

80 pages / $15.95 Buy from Amazon or SPD

Robert Frost’s “Out, Out—” depicts perhaps the most famous dismemberment in American poetry: a young boy loses his hand while working with a buzz saw, bleeds to death, and at the end of the poem, his parents indifferently “return to their affairs.” The poem induces a naturalistic sense of spiritual doubt, and it’s also suggestive of a wartime paranoia about technology’s potential for violence and destruction. Jamaal May’s debut collection Hum (Alice James, 2013) is driven by a relentless confrontation of the lines between natural and artificial, and it reinvents all of our typical assumptions about the relationship between technology and humanity. In a sly invocation of Frost, “Hum of the Machine God” depicts a father who loses his thumb while operating a snow blower. But unlike Frost, May doesn’t evoke the expected sense of lost innocence: the boy is not the victim of the tragedy, but rather, the witness. The machine isn’t a harbinger of modernist alienation, but rather, a spiritual entity in itself:

Gripped his shovel. Gripped his oar. Now, in a waiting

room, he bows to the florescent hum and begs. Ignore

my prayer, goes his stupid little prayer, please ignore

my voice. The thumb in a jar packed with snow,

will take a miracle for the doctors to reattach.

The poem sets the tone for the collection: there’s a sense of deep uneasiness about being alive, a constant teetering on the edge of violence and danger. If it seems risky to confront Frost, it’s worth noting that this is not only the second poem in the book, but also a sestina—a usually clunky form into which May breathes life (despite the fact that most of us can probably count the number of interesting sestinas we’ve read on one intact hand).

Numerous poems in Hum are concerned with machines: we see factories, broken-down automobiles, grenades, dead frogs stored in freezers, fallen industries—the book itself is dedicated in part to “the interior lives of Detroiters.” But in Hum, machinery isn’t a predictable representation of modern despair. Instead, it embodies a spiritual force, presenting a potential for energy, for both violence and renewal. May creates a world where the brand name of a G.E. freezer can stand for “God Engine,” and an appliance can stave off death and decay while “fly-dotted pears rot,/corpse-soft on the table.” Through a kind of inverted Romanticism, the poems waver toward the possibility of injury, often evoking a discomfort with the bodily and organic. Artifice is appealing precisely because of its ability to resist decay. We see this in the particularly memorable poem, “If They Hand Your Remains to Your Sister in a Chinese Takeout Box,” when the speaker encourages the reader to “Take solace that the plastic bag/carrying you to the cemetery will…/spend decades holding hands with a breeze.” Whereas the artificial, manmade world is (seemingly) able to transcend time and death, the human body is flawed. From “I Do Have a Seam”:

careful seamstress, you

needle in my sternum—

stitch my selvage as it frays,

you know how ragged I’ve been

Here, the “seam” is suggestive of the suturing of existence, of human imperfection. The poems in Hum exhibit an anxiety about death, decay, and in particular, stagnation. In a nod to Dickinson, May suggests, “I get it, you got sick/of your life standing like a loaded gun—/everyday with me another hangfire” (from “Macrophobia: Fear of Waiting”). Anxiety is not only a driving theme in the collection, but is its structural backbone—the book is organized around a series of poems about phobias (“Chionophobia: Fear of Snow,” “Thalassophobia: Fear of the Sea,” etc). Often, mechanization serves as an antidote to this sense of fear, bringing a potential for order and stability to an otherwise fragmented existence; the speaker of “I Do Have a Seam” hopes to resolve the “seam” through “the sewing machine of your hands.” In “Masticated Light,” the speaker describes the experience of being blind in one eye, a problem which can only be resolved through technology:

and it’s like aiming through a gunsight;

even the good eye is only as good as whatever glass

an optometrist can shape.

If Hum considered technology solely within these parameters, it would likely lose energy. But as the collection progresses, the categories of “body” and “machine” become increasingly blurred, eventually collapsing into each other:

some more complex than others: needle-

nosed pliers, pistols, a satellite—all ignoring

my commands to sit still. (from “The Hum of Zug Island”)

What makes Hum stand above so many other debuts is not only May’s willingness to expose his own vulnerabilities, but that he isn’t paralyzed by his personal perspective. The poems move increasingly outward from the self as the collection progresses; in several poems specifically focused on war, technology’s potential for violence becomes fully realized—war begins to function as a kind of machine. In “Pomegranate Means Grenade,” one of the strongest poems in the collection, violence arises from the blurring of the natural and artificial:

means pomegranate and granada

means grenade because grenade

takes its name from the fruit;

identify war by what it takes away

from fecund orchards

By the end of the poem, it becomes increasingly clear that “hum” refers not only to the soundtrack of a mechanized world, but to the sound and vitality of language itself. Words bridge the fissure between natural and artificial—that’s how we find commonality between pomegranates and grenades. But ultimately, language doesn’t serve as an antidote to disorder. Rather, it functions as a mode for contemplation, and maybe, renewal:

Sometimes those words quiet the machines,

the hum gets easier to ignore. But pine needles

still fall gold. Dead trees creak. A rain-gutter sea waits,

machine-gray, and my throat beings to drink the snow.

***

Marty Cain received his BA from Hamilton College, and is currently an MFA candidate at the University of Mississippi. His poems have appeared (or are forthcoming) in The Journal, PANK, The Minnesota Review, Rattle, and elsewhere. Find him online here: http://watchyourfeet.

Tags: Hum, Jamaal May, Marty Cain

[…] as Marty Cain insightfully points out in his review, “…in Hum, machinery isn’t a predictable representation of modern despair. Instead, it […]