I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

Edited by Caroline Bergvall, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody, & Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, 2012

455 pages / $40 Buy from Les Figues Press

(Disclosure: I honestly had no idea when I requested the book but note that it contains the work of some of my friends, acquaintances, teachers, mentors, and personal heroes, though the widescreen approach in curating the book’s 64 writers works against me simply cheering on a select group or writer to whom I’m personally attached.)

Prior to reading I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, my general, sloppy idea about conceptual writing was that it was only the kind of writing where the experience of appropriated text as object/concept was more important than the experience of reading what’s been sculpted into book form for “literary” value. Instead, I’ll Drown My Book offers approaches to encountering and writing text as various as the writers included and as familiar as “appropriation,” “intertextuality,” “hybrid” and “constraint,” named in the book alongside “dissensual,” “baroque,” and thirteen other broad categories as forms conceptual writing might take.

What’s important and unique about the writing in I’ll Drown My Book isn’t what strategy is being employed but the fact that there is a strategy, and often a structure. (The two being different in that strategy involves an approach guided by a given or created set of rules while structure involves use of a given or created form other than a continuous or broken line.) You could claim that all writing is strategic in some way with respect to what decisions you make when you set out to write anything but the writing in the anthology is strategic specifically because the strategies are local, formal, and often overt vs. obscured from the reader. Conceptual writing, here, is not a movement but a methodology, a way of viewing writing as always following and rewriting a myriad of different kinds of other texts, or by replacing “writer” with text. Just for the sake of contrast I’m claiming the nominal state of what let’s call “normative” writing is that you can and do claim sole authorship,over additive and usually linear text, starting off in your headspace with an idea or image or voice that seems worth pursuing and building on it alone, meaning, in the words of Frank O’Hara, you just go on your nerve.

The writing in I’ll Drown My Book sometimes does go on its nerve after setting up relevant guidelines, and “generative” is even one of the categories included though it’s not explained how that’s meant, but as a whole, strategy either prefigures or dominates the writers’ production. Sometimes that strategy is explicit, as with Nada Gordon’s work from The Abuse of Mercury, which reads like phrases taken from a prior manual on what happens when mercury is abused, the text rendered suggestive by elision:

Hot face with cold hands and feet.

Great tension, anxiety, fear.

Fear of a crowd, of the future, of the seriousness of his illness; feels sure he will die.

Or again when Laura Mullen borrows from Wordsworth to address the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in “I Wandered Networks Like a Cloud”:

In one hand, drink in the other, a crowd

On the screen (wounded, enraged)

Fleeing the tanks beneath the leaves

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

And then Mullen progressively distorts the form of the source material as in this, from “No Voice”:

Wandered lonely as a variety of complaints in a voice of another who had no voice

This is what I remember

Two figures by the water’s edge, stopped by such beauty, one numbers

What Mullen does in the two preceding poems isn’t simply using the form of the original as a container for contemporary material, but by rereading the choices Wordsworth makes using his sister’s journal to build a narrative, so that wandering and lonely (for example) each become an axis around which Mullen can wind both her retelling of the poem and her retelling of being witness to the Hurricane Katrina tragedy. Mullen wanders the Hurricane the same way she wanders the original poem, giving a voice “in a voice of another who had no voice” to different kinds of memory and history connected as conceptual exploration.

And sometimes strategy is less readily apparent, as with work from Angela Carr’s Rose Concordance, a complexly structured translation and redistribution/realignment of text from Guillaume de Lorris’ Roman de la Rose:

i’d like to naively delete the deiform source

in this critically naive and

complicitous gamble with humanism

of the prefeminist fountain, gushing is essential

existence is an aromatic crease

Carr’s approach and result is different from Mullen’s in that Carr’s is organized around “key words” in the source text and so it’s not the form of the original being appropriated, it’s certain throughlines of content. The text is a structured starting point for generating content that echoes, responds to, and even obscures the original by being organized by terms instead of whatever overall meaning de Lorris might have been attempting to get across.

Another feature of conceptual writing as framed by the book is that it actively disrupts the linear nature of self-generative writing (experimental or not) most often by arranging the words-as-material on the page in a way that requires viewing as much as reading. One example in the book would be Jen Hofer’s quilting:

Hofer has physically stitched together fragments of found printed text into a quilt from which text can be read through Hofer’s decisions about both what material she’s chosen and how (and why) she’s chosen to stitch it together. Each writer in the anthology is given room for a critical statement about their work or conceptual writing and for Hofer, the “why” is a proclamation that “I have nothing to say,” that “There is nothing new to say,” and that the slow process of quilting gives her a great deal of time to consider ideas being dealt with, time you might not usually want or be able to spend when encountering any given text.

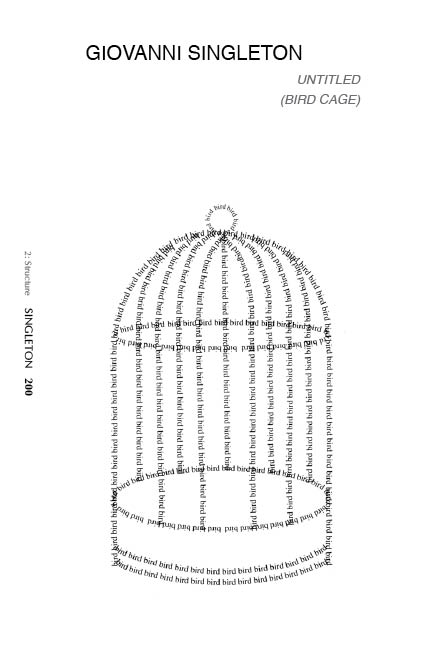

Another example of the visual nature of much writing here is Giovanni Singleton’s “Untitled (bird cage),” which is a drawing of a birdcage formed out of the repeated printed word bird.

As far as the work goes that may at first seem pretty straightforward but there’s more going on than that, as with all of these interventions and reckonings. In this case the work is “soundtracked” by Charlie Parker, which loads the text/image with plenty of meaning as it is if you know any Parker biography, but is also “a response to and dialogue with” Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “Sympathy,” the first line of which is “I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,” loading the work with an entirely different cultural/textual context, Dunbar via Angelou.

That the dialogue or strategy isn’t necessarily transparent in the finished work doesn’t mean either the strategy or the result is a failure, though, simply that whatever methodology or source material is involved need not always be presented as convenient explanatory footnote. Instead it’s textual recreation and reaction that matter most. The strategies used here, the text encountered, the context of the text and the final results all have lives separate from each other even though they’re interwoven via structure, labor and critical thought. It’s as meaningful that Singleton’s cage is empty as it is that it employs a strategy derived from or in response to other text or context you may or may not intuit or already know, for example. Or you could be given the references and told about the piece and that wouldn’t be the same as reading it but you could still get something from it. Strategy is important, but how the text was produced is only as interesting or important as what gets produced, what’s on the page in I’ll Drown My Book when writers begin writing with text(s) already in hand or by attempting to erase “the writer” (and sometimes the writing) from the page.

That still leaves the question of whether I’ll Drown My Book does part of an anthology’s work in effectively summarizing what it contains, and the answer is not quite. And per the editors that’s only to be expected. Conceptual writing is maybe willfully too broad and amorphous of a kind of writing to be covered comprehensively by any one collection of work. But it’s a glorious not quite because it leaves room for fucking around, as in Kathy Acker’s “appropriation” of Great Expectations excerpted here, for rule-breaking, and for denials and refusals. What the anthology does do is present conceptual writing as something multivalent and full of possibility for both writers and readers, a rendering of strategy and of reading-as-writing not as a dry exercise but as play, conceptual writing being something overstuffed with connections to the world that produced the texts and contexts the writers here reckon with so compellingly.

***

This is Part 3 of a week long feature on I’ll Drown My Book, the new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

***

Nicholas Grider is an artist and author whose artwork was most recently featured in a solo show at the Armory Center for the Arts in Los Angeles and whose writing has recently been published in Conjunctions, Drunken Boat and other magazines.

Tags: I'll Drown My Book, Les Figues Press, nicholas grider

[…] Wednesday – Part 3: Review by Nicholas […]

Every Tom, Dick and Harry.

There is no equivalent to this in the other gender, no felicitous phrase.* Every Jane, Sue and Molly does not work. It seems to me that the writer of English is the guy [sic] who is hip to this.

*Note: Sometimes the written word and the spoken word ( speech ) come across differently in English, but here the affect is the same.

[…] words are nicholas grider on i’ll drown my book Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

[…] words are nicholas grider on i’ll drown my book Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

[…] This is Part 4 of a week long feature on I’ll Drown My Book, the new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3. […]

[…] of it, writing maybe that unlike the more engaged conceptual writing found in great books like I’ll Drown My Book SLCW is sort of like the kind of joke that’s only funny the first time. The novelty wears off […]