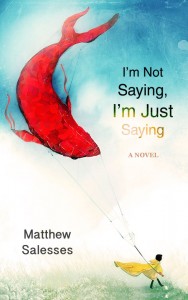

I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying

I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying

by Matthew Salesses

Civil Coping Mechanisms, February 2013

138 pages / $13.95 Buy from Amazon

Koi fish have hundreds of scales that form a protective armor around them. Matthew Salesses’s I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying is a collection of 115 flash fictions that, like those scales, explore the spoken and unspoken nuances that connect and glue relationships in all their misfit forms. Many of the characters go unnamed, a decision that suggests that the companions symbolize divergent desires. There’s the wifely woman who’s his main lover and there’s a “white woman” who acts as a mistress as well as another Korean woman who is in place “for emergencies.” Each serve a different need, though none can satisfy him because he partitions himself like the segmented chapters that comprise the book. They are lyrical segments akin to jazz solos forming a striking concerto of prose. The impetus that triggers the journey of the book is the appearance of a son he never knew he had. When the boy’s mother, an old lover, passes away, the narrator takes the son into his home. Rather than a definitive reaction to this revelation, there’s a miasma of conflicted emotion, an uncertainty that could best be summed up in the piece, “She Was a Tsunami to His Earthquake:”

His lovers, his co-workers, and finally, his son, form a tenuous thread that bind the invisible wavelengths of his life together. Only, he is always trying to split them apart and keep them isolated in a delicately stratified web. In describing the side girl-on-the-side, he says: “I had to be careful with her, though I wasn’t technically married, because she collected the crumbs of truth, but for an hour with her, I was someone else, and when I left, I could discard that part of me and know it would be repossessed.” The elegance of the book lies in the poetic congruence with which his life is shattered by circumstantial incongruence. Say, for example, his observation at an art gallery with his son that only the letter T separates the word “paint” from “pain.” This was an association formed from his failure to be the artist he aspired to be as a freshman in college. He is protecting himself from pain, but entering it willingly to try to teach his son something about painting. That contradiction of both being in the mural and trying to control it hints at the theme of a man all too aware of his foibles and flaws, but still is helpless to do anything about it. Twisted accents in his relationships add shades and make every interaction a layered strip tease, tantalizingly bare without showing anything essential:

There’s a charm and wit in this narrator who juggles relationships like pins and an ambivalence that reflects the title’s declarative uncertainty. Racial stereotypes, interracial dating, and cultural dichotomies are handled deftly without being heavy-handed as when he “took the boy to L.A. since he barely knew he was Korean,” a funny little insight considering Los Angeles has one of the biggest Koreatowns in the world. “‘How big is Korea?’ he asked. I told him it was sized to slip through the cracks.” At times, we hope the narrator will be able to maneuver his way through all the traps he’s set for himself. Eventually though, his affairs catch up with him and his working politics get him in trouble at work. Worse, he is nowhere near an understanding with his son and it appears the wifely woman wants him gone after discovering his infidelity. He can’t hide in bouts of denial, his egresses hoping for physical intimacy are forbidden, and no flourishes of witty insight can will away his plight.

It’s the intersections between the scales that makes I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying, so interesting— those vulnerable spots that expose flesh while desperately trying to protect against it. I think of composite images made up of multiple portraits to form one that can only be seen from afar. Matthew Salesses, through these 115 separate pieces, forms a picture similar to a pointillistic portrait. The relationship between the macro and micro view is as ambiguous and clear as that of all connections the narrator has with those around him. It’s part of what makes this collection so bold and yet so intriguingly elusive. I’m pretty sure I know what Matt Salesses is saying. At the same time, I’m pretty sure I don’t know what he really just said.

***

Tags: civil coping mechanisms, I’m Not Saying I’m Just Saying, Matthew Salesses, Peter Tieryas Liu

[…] Koi fish have hundreds of scales that form a protective armor around them. Matthew Salesses’s I’… […]