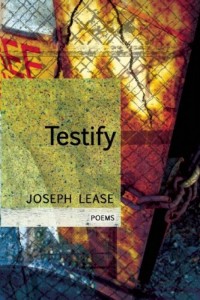

Testify

Testify

by Joseph Lease

Coffee House Press, 2011

63 pages / $16 Buy from Amazon or Coffee House Press

In his latest collection, Testify, Joseph Lease pulls words from a wide stream of diction, using vastly different textures to make the fullest contact with his readers. Re-casting lines from multiple news sources, Lease sets up the problematic linguistic backdrop of the current media and the gaping lack of a faithful source of social, economic, or political truth. The action of writing, even the intention to “turn off the shooting try our new / daydream and / try our // new rights,” offers an intervention, an alternative to the automatic moving walkway that propels us always in the direction of consumerist distraction, militarized deception and political numbness.

This mixing of language sources runs horizontally and vertically throughout the poems, always accompanied by what seems like the intention to write into language a new kind of critical and essential love. With lines like “We’re going back home to / night pushes through money” and “write to your congressional representative, / write to, keep imagining—,” these poems literally invite readers to return to a more compassionate model of democracy, in which there is a “home” to return to, perhaps the home of collective action around the demand for true social investment outside of capital or military “growth.”

Made of four discrete sections, “America,” Torn and Frayed,” “Send My Roots Rain,” and “Magic,” Testify sings from a lyric “I” that is at once outraged, grieving, tender and hopeful. Lease retraces phrases and rhythms to build tremendous richness and depth over the seventy-five-page work. Bleeding through the borders of its separate movements, the book circles back, widening and deepening the connection between speaker, listener and poem. Some of Testify’s parallel undertones are subsurface as a pulse—and I can’t be sure if it’s my heart that’s making them or Lease’s. To me, this is the central force of Lease’s work; this beautiful tangle of breathing and moving makes direct contact, which Lease has forged through a kind of shared organ. Take, for example, the opening lines to “America,” the poem that comprises Testify’s first section: “America // Try saying wren. // It’s midnight // in my body, 4 a.m. in my body, breading and olives and / cherries. Wait, it’s all rotten. How am I ever. Oh notebook.”

From this first line Lease roots down immediately in both body and voice. His focus on effort and embodiment in the face of disorientation, dismay and deception, creates a space for shared experience and hope.

Moving quickly into war on the next line, Lease connects a national identity crisis, “A clown explains the war….Oh CNN,” to a personal one, “I have to run, eat less junk.” The effect is to model a consciousness of citizenship that never seeks to isolate the self from the collective: “say democracy: say free and responsible government, say / popular consent.”

For Lease, what’s going on in the body, in the interior of a citizen’s mind and soul, is deeply tethered to the rhetoric and deeds of his geographic location. The series “America” calls, then, for a reaching out in effort, attention and action, toward others: “There’s a fist of meat in my solar plexus and green light in my mouth and little chips of dream flake off my skin. Try saying wren. Try saying mercy.”

Along with the just-woke-up feel in the “dream flake” moment is the sense that it’s a particular or even that infamous American Dream that has literally hardened into a kind of shell or exoskeleton and is chipping off and away from the surface of the speaker’s body. The willingness to expose human frailty and sorrow in physical terms is a rare value in current poetry, particularly in light of the various forms of suffering in the world. Lease doesn’t shy away from this action, which brings his readers in close. “Like a body come undone, you are past the water’s skin.” Or, in the parallel faltering of the state’s body, “say democracy so polarized, say polarized, say paralyzed.”

Ginsberg writes this line in his poem addressed to America in 1956: “America this is the impression I get from looking in the television set. / America is this correct?” And Lease continues this line of questioning, adding the uncanny genre of reality TV as another impediment that reflects what has been fabricated for what is real: “and you can’t / get to the real world, they keep showing / the real world on TV.” Lease wants to push past surface, past easy perceptions and reductions to find what matters and to keep it in its context. “Voices you heard one night in town, just beyond the / strips of light.”

Pulling back a bit from the public address of “America,” the speakers in parts two and three of Testify address more intimate yous. “I wanted to cultivate sky-blue / emotions,” Lease writes in the long elegy “Send My Roots Rain,” followed a few pages later by “you came back to the / world: the green world, the fertile world, the corn world, / the gun world // You came back to the world and there was / nothing there.” While the landscape is as dangerous and beautiful as it is in “America,” the characters are in closer, domestic scenes: “the old couple in the kitchen, / lights out, lights out, waiting for sound.” Though they seem to live now in close proximity to their beloveds, they still encourage each other to continue the personal-public lyric: “turn toward night, speak into it.”

The last section of the book, “Magic” reminds me of C.D. Wright’s socially-engaged poetics—“please / breathe my / newsprint”—which is always glittering with particulars of personal life, even or perhaps especially when she is working with documentary methods, as in One Big Self or One With Others. Lease also weaves statistics with the romantic, “5% of the / world’s, 25% of the world’s, population, resources, you know all this, sure you do: minivan, Ativan, moon in my hands,” and “branches, desire, little ifs of white spin in the bowl.” I am struck by sounds and visuals, as anagram-inspired word riffs transform a pill to the moon to a bowl. Perhaps most lovely are the tiny letters, such as this one:

“Please—

What is ‘the good life’—

Dear You,”

Beyond the profound and unanswerable questions they raise about the purpose of life and about desire, these missives seem also to answer them by offering a handmade reaching out to each and every one of us.

Lease’s poetry enacts the questioning, challenging plea of a speaker struggling to stay connected to his own judgement, his faith in humanity, in the power of the collective to feel, recognize itself and act. This work, among the best poetry of our time, is full of conflict, contradiction and the vitality of thinking. That is, thinking while feeling while thinking and trying to sift through it all, and back, finally, to some enduring shelter in a self-aware language.

***

Jesse Nissim is the author of Day cracks between the bones of the foot (Furniture Press Books), SELF NAMED BODY (Finishing Line Press), and Alphabet for M (Dancing Girl Press). Her poems have appeared in 26, Barrow Street, Court Green, ecopoetics, H-NGM-N, New American Writing, Requited, RHINO, La Petite Zine and others.

Tags: Jesse Nissim, Joseph Lease, Testify