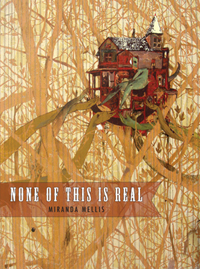

None of This Is Real

None of This Is Real

by Miranda Mellis

Sidebrow, April, 2012

115 pages / $18 Buy from Sidebrow or SPD

O, the subject of the title story of Miranda Mellis’s collection of short and long fiction, None of This Is Real, seeks solace (he has headaches—better to say “pain management,” then? we’ll see) in something called “Path to a Position™,” purveyed by its shadowy practitioner, Tiara Scuro: “She outlined for O the steps by which he would, with her, find his position. . . The old school believed the antidote for despair was courage, she said, but the real anti to the dote is a comforting distortion; this is what I call somatic realism.” “Somatic” realism? Is there another kind? Or do we deal in phenomenology?

“For years I had been removing the ground from under my clients,” she tells him,

What she means is a pose, a posture (“standing in a curious way with his head turned all the way to the left and tilted slightly forward,” in O’s case), the steady ground of an unshakeable confidence (think of your least favorite Presidential candidate), the brute intelligence of complete insensibility—ignorance, in other words, an absence of empathy. An existence as inscrutable as an animal’s. This is the problem that Mellis’s characters confront, over and over: what to do with themselves, stranded somehow in their bodies by their suspicion that the something more that they are that isn’t corporeal is not just immaterial but unmanageable and inhuman.

For O, the carefree (thought-free, anyway) Position Dr. Scuro proposes is untenable. It does not cure—and may cause—his headaches. Something snaps, returning him briefly to thought, from stasis to story:

Yes, we’ll go on. O, Sonia, Tiara Scuro — the story’s a study of how we go on, or rather, whether we go on. O has long ceased to do so despite his words, stopped in his tracks by this positional therapy. “Stereotypy,” “somatic realism”? In None of This Is Real, all the rest is a fiction. The O of O is just a story. Without O telling O, there is no O, or rather there is 0, a body: “he slumped down below the rodeo sign and shucked off his corpus, a specter rippled out, heading west to the sea.” And so he goes on. Or rather, doesn’t.

“Keep a picture of yourself outside your own head,” touts the photographer working the Cortazarian line to the coffee shop in “The Coffee Jockey,” but even when he has a taker (the “coffee jockey” herself), no one’s really buying it. None of this is real, remember? Or rather, what’s real is what these characters aren’t, their bodies moving through the world in advance of the stories that they tell about themselves (creating, in the process, themselves (and, of course, fiction: “what’s the difference between imagining and knowing?” wonders a character, and, well, there is none)): “The man stood and his leg lifted, then his other leg. The leg lifted and bent at the knee, he proceeded forward, then the other leg lifted. In this manner he walked. He placed one foot on the ground, then lifted his other leg and placed the other foot on the ground.” Mellis’s philosophical conundrum is that of Descartes: what to do with dualism, where to locate the self.

So maybe it’s not ontology after all. Maybe it’s something more immediate than being—the stuff of being, the fiction of the fiction. In “Triple Feature,” a young girl bargains with no one for a life (her mother’s) that is not in danger: “She had no clear sense of whom she was bargaining with, just that it was someone powerful and willing to barter, someone who would accept her pain in kind, even her body parts in exchange for her mother’s safety.” And yet her mother slips away. How do Mellis’s characters go on? By telling themselves stories. By telling themselves. The girl’s bargain might have worked, but she forgot to make it until it was too late, too caught up in her body:

Bodies again—not only not selves, but not even part of the self, currency; the self can be embodied by any body, any body at all, or else what is the imagination? The transformer of “Transformer,” Moira, is a kind of Guy Montag of performance art, a spirit medium of motion: “Re-creating canonical performances had been her métier. . . She chanted, shouted, danced, flew, and deployed all manner of apparatuses to recuperate the art of her brief lineage.” Recuperate, not revive. There is no reanimation here, the body is long gone:

And somehow this is cheering. The waste our bodies are is nothing to be ashamed of because it isn’t even ours. You might as well be ashamed of someone else’s big nose, someone else’s birthmark. Well, you might as well; Mellis’s “somatic realism” is irreal, unreal, the actual artificial.

The sad somatic reality is that the body grows and falls apart at the same time. Time is the deus ex machina in all our stories, the shape that our stories all have: “Now she saw that the road she thought had moved forward was going back. It would not be possible to go on after all.” No, I guess not. Not for these characters. Not with a body. And what happens when you can’t go on?

Why is it that so many existential metaphors seems to involve some kind of bureaucracy? It’s the body’s inexhaustible inefficiency, isn’t it? Because if the body worked the way our minds do, dualism never would have been conceivable. None of This Is Real depends on what This refers to. Or else what Real refers to. Or maybe Is. Or maybe I.

***

Gabriel Blackwell has two books coming out at the end of the year: Shadow Man, a novel, and Critique of Pure Reason, a collection of essays and fiction. He is the reviews editor of The Collagist, among other things.

Tags: Gabriel Blackwell, Miranda Mellis, None of This Is Real, Sidebrow