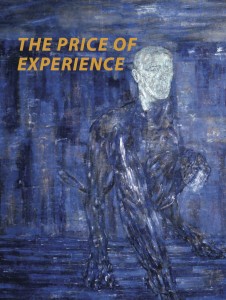

Price of Experience

Price of Experience

by Clayton Eshleman

Black Widow Press, 2012

483 pages / $24 Buy from Amazon or Black Widow Press

The Price of Experience is a broad sampling of Eshleman’s prodigious output in a variety of literary forms: poems, letters, interviews, book reviews, essays on contemporary art, and lectures on ice age cave art, are all brought into the mix alongside various memoir bits and notes on his numerous translation as well as editorial projects. (Eshleman indispensably translates the poetry of both César Vallejo and Aimé Césaire, among others. He also edited the seminal journals Caterpillar and Sulfur.) This would be considered an “Eshleman Reader” if only somewhat incredibly it didn’t follow on the heels of Black Widow Press’ previously published The Grindstone of Rapport: A Clayton Eshleman Reader (forty years of poetry, prose, and translations). Meanwhile, it also looks forward to their publication of Penetralia (a fifty-seven-year poetry retrospective) in 2015. It’s daunting (and perversely thrilling) to imagine what the page count for the upcoming “retrospective” might turn out to be as the other two books come in at around 500 pages each.

Eshleman grabs his book’s title from lines of William Blake’s The Four Zoas and the lesson expounded by the work of the poet-mystic-printer is ever apt. Eshleman quotes an extensive passage, but here are the opening lines:

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath his house his wife his children

Wisdom is sold in the desolate market where none come to buy

And in the witherd field where the farmer plows for bread in vain

In essence, given this epigraph, which ends “It is an easy thing to rejoice in the tents of prosperity / Thus could I sing & thus rejoice, but it is not so with me!” Eshleman seeks to frame this retrospective accounting of his work in a fashion which demonstrates how thoroughly his writing arises quite literally from struggles surrounding the circumstances in which he’s lived. There should be no doubting that Eshleman has done his fair share of downward scraping into the barrel of experience, bottomless as it may be. He has always returned to his work positioning his imagination via writing in the hands of forces over which he often feels no control. The resulting discoveries astound him as much as anybody else. In fact, they sometimes astound him quite a bit more than they likely do anybody else.

The limits of Eshleman’s writing arise when his impulse for self-expression overrides and self-indulgence swells within him, his proclivity for excess then gets the better of him. One case in point: while detailing his relationship with poet Paul Blackburn, Eshleman describes how his own personal demands tore him away from composing a poem for Blackburn’s second wedding and instead turned him towards writing a massive poem—as yet unpublished in its entirety—full of his working through deeply personal psychological material from out his own past.

Occasions of writing such as the one above have without doubt proved essential to Eshleman’s self-understanding and his personal relationships were most likely improved by his exploration of such areas of self-development, yet the fact that this lengthy poem remains unpublished is telling. Even more to the point, just how this detail adds to Eshleman’s commentary on Blackburn’s work is a bit baffling. What happened to the poem for Blackburn’s wedding?

Eshelman, perhaps despite himself, is however quite capable of writing free from the influence of these nagging quagmires. His adoption of the poetic personae of poet Hart Crane in “A Visit from Hart Crane” at the opening of his travel notebook of poetry and prose “Our Journey Around the Drowned City of Is” has all the force of an undeniably significant leap of imagination without too much of the abrupt, over-exposed Eshleman psyche. Crane’s work and biographical elements of his life are clearly feeding into Eshleman’s senses, awakening a powerful third triangulated voice:

This shows what it means for one writer to be haunted by another writer’s work. To have real things enter her daily reality from off the remembered page of reading. It is true poet’s work.

Eshleman’s decades long extensive engagement with ice age cave art found around southwestern France resulted in Juniper Fuse: Upper Paleolithic Imagination & the Construction of the Underworld. Included here are his lecture notes for pre-tour talks he gave to small groups he led into several of the caves over the years. There’s little doubt that the thought and research Eshleman put into this area of study make it among the defining accomplishments of his lifework. He manages to succinctly cover a lot of ground, never spreading his own story over what’s already up on the walls.

Particularly fascinating is revelation of the possibility that Ezra Pound may have visited one of the caves, Combralles, during the walking tour he took in 1912. From a published selection of drafts of The Cantos, poet Robert Creeley pointed out to Eshleman a set of lines with references such as “at les Eyzies, nameless drawer of panther, / So I in narrow cave, secret scratched on a wall,” and “…in the narrow dark of the crevice / On the damp-rock, is my panther, my aurochs scratched in obscurity.” As Eshleman argues:

The feeling Eshleman’s writing demonstrates for the caves, matches the immediacy of image to be found in Pound’s own work. It’s also simply fun imagining a young Pound scrabbling about in one of these caves back before they became destinations for the massive amounts of visitors which have resulted in caps and restrictions having to be imposed by authorities to the extent that in some cases access was shut down or severely restricted even for official research. Pound was in them back at a time when the caves were as casual a local discovery as I remember walking through some Southern California sewage drainage pipes and canals to be for myself and friends.

As Eshleman reminds, many of these caves are still looked after by the family who owns the land and who perhaps even had a hand in discovering them. For instance, among the most famous caves, Lascaux, became known after two teenage boys (who later became caretakers) dropped stones in a hole beneath “a toppled Juniper” and then later returned to explore the underground space and saw the paintings. In the end, they are just another one of those things you might come across like anything else. Whatever interest they hold for viewers is ultimately based upon the adventure into the unknown. Similarly, Eshleman’s writing when at his finest fully arouses the interest of readers when it ventures into unfamiliar territory, unrestrained by limitations of obvious self-interest.

***

Patrick James Dunagan lives in San Francisco and works at Gleeson library for the University of San Francisco. Many book reviews appear here and there. His most recent books are A GUSTONBOOK (Post Apollo 2011) and Das Gedichtete (Ugly Duckling 2013).

Tags: Clayton Eshleman, Patrick James Dunagan, Price of Experience

great portrait of a great maniac! (thanks!)

tinyurl.com/l3cselt

v