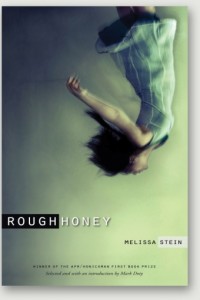

Rough Honey

Rough Honey

by Melissa Stein

The American Poetry Review, Oct 2010

96 pages / $14 Buy from Amazon or IndieBound

Melissa Stein is the 2010 winner of the APR/Honickman First Book Prize for her book, Rough Honey. In the introduction, Mark Doty notes that Stein’s “sentences are beautifully choreographed; they start and stop the motion of her poems with a nearly invisible, effortless authority. Best of all, her concurrent attention to sound and to image makes the world, on these pages, viscerally real; she employs one of poetry’s oldest powers, yoking the referentiality of words to their sheer sonic force ” ( xi).

I don’t remember where I was when I first read one of Stein’s poems, but I do remember that I immediately ordered the book. I was struck by the combination of visceral and sensual language of her work. In “Whitewater” she begins with the flip of a kayak and an adrenaline rush:

like academics, frothfoamgrit and the taste,

what was it, asphyxiation, psychedelic Escher

in blackwhite cubes (6)

There is something sensual, almost first sexual experience whimsical in linking froth, foam and grit into one word to illustrate the initial plunge. There is a hint of the graphic results in her word choice “asphyxiation” (6). The shift upon the speakers face plant into a rock is an unusual blend of both sensual and visceral:

White protrusion of bone – white petals and light,

Pearl-solid, luminous, all fourth-of-July and scattered,

Pipe bombs bottle rockets Christmas crackers, oh,

What a party, annihilation (6)

The leap from “white protrusion of bone” to “petals and light, / Pearl-solid, luminous” (6) and pairing “Pipe bombs bottle rockets Christmas crackers” (6) is an example of what Hoagland (2006) calls the “pause that would never occur in “natural”, uniformed speech” (62), a self-conscious move that deepens the experience of the poem. It brings a range of emotion to this singular event, from war to holiday, in very few words.

Her voice is similar in style to how Hoagland describes Louise Gluck’s in his essay, “The Three Tenors”. Here, Stein’s “radiance and gravity [like Gluck’s] grow out of the enormous pressure exerted on the contents of a small container” (Hoagland 52). It’s no surprise since Stein considers Gluck to be one of her early influences.

Her tone is dialectical, passionate, detached. Stein shifts the tone of her poems by using the interplay between the sensual and the visceral to detach and create space. Again, in “Whitewater” after the initial thrill followed by impact, the speaker reflects on the surroundings in a sensual way as if none of this has happened:

the tenderness

of paint sable-brushed against silk, powdered

throat of the foxglove, flushed curve spiraling/into a conch

velvet crowing the doe’s nose,

arms embracing the cello’s hips” (6)

Here, she clearly illustrates what Doty has called the “start and stop motion of her poems” (vi). There is the flip/rush, the smashing of face into rock followed by that place where this is no pain.

Her themes tend to be grounded in relationship, but it is not always obvious from the start. There are twists and turns. In “Apologia” Stein begins with describing the impact of flooding and brush fires on wildlife that create a “terrified stampede / of smoke-choked bodies, green cells charred to black. / the pack will leave behind a wolf so ill / he’d hinder the hunt” ( 31). There is an ominous, visceral tone to this piece until she slips this in: “I wish I’d been kinder/ to you” (31). Talk about a stop.

She uses metaphor in a very global sense. In “Trouble” she uses the physical landscape of the prairie to tease out the story of a man in search of his daughter described as “the doll he lifted to the swing and pushed until her feet touched the sun” (44). We know there is trouble from the title. Using the flora and fauna of the area, the man swipes, flattens, and displaces in search of the girl until he reaches the wood and the trees whisper, “won’t give her back” (44) and “he kneels in the jewel-weed its jester cap blooms” (45). The landscape has the last laugh.

Stein has a way of delivering these dark themes in a way that is sensitive to both the physical and emotional pain. In “Trouble” although the initial focus is on the man’s disregard for the earth, understandable in his frantic search, in the end, he kneels in the very landscape he has destroyed. There is a deeper angle here, a bigger story that messes with your head. Neither the landscape nor the man appears brutal. Instead, they consume and console each other.

Doty notes in the introduction that Stein’s book does not focus on a singular theme. I beg to differ. Relationship permeates her work. There is a consistency here, personified in the title/metaphor Rough Honey. Like the book’s title that is almost an oxymoron, but not in the strict sense of the word, her poems consistently employ the stop/start, push/pull, attach/detach tone that Hoagland calls “the complex system of detachments in relationship” (84) that provide space in a poem to breathe and relationship is the angle.

Stein infuses her work with causality; the antecedent and consequences are unexpected. This is beautifully evident in “Ground Fire” which begins with the image of a couple trying to catch lightening in a field in sensuous prose, “feeling the small flame on my thigh, it barely moved/ but spread” (76) than moves to “tinder, twine, what binds” (76). This passion, the antecedent leads to “the veins of fire beneath the soil that hide” until “my grandmother’s house, we couldn’t save it” (76). There are all kinds of layers here – the passionate moment, perhaps producing the electricity that sparks the fire, real or imagined, that ultimately takes down the house. However, it is not clear cut. According to the poem, “there wasn’t any lightening” (76) and despite the neighbors’ efforts, the speaker asks “what could douse a conflagration like that?” (77). There are two parallel themes running through this poem; the relationship and the ground fire. Stein has used the material world, the dynamics of a ground fire, to give structure to the poem.

Stein does not end “Ground Fire” here. Like “Trouble” she ends with “It was beautiful, god, a field set afire/ by the sun, and smoke so thick it blotted out the moon” (77). Perhaps the moment was worth it.

There is an odd peace in her poems. I find this to be endearing and her saving grace. In a recent interview with the SF Weekly Blog: The Write Stuff: Melissa Stein on the Literary Mood Swing, when asked what kind of writing she would like to do, Stein answered, “Ideally? Write poems that are the love-children of Hopkins, Plath, Millay, Cummings, early Louise Glück, Linda Bierds, Gerald Stern, Alice Munro, Laura Kasischke and Robert Thomas — all wrapped into one. I’d be such a badass.” (July 11, 2013) In fact, “Ground Fire” resembles Hopkins own poem, “As Kingfisher’s Catch Fire” with the essence of Millay’s “Afternoon on a Hill” and a hint of Laura Kasischke’s “After Ken Burns.” Her work is a literary cocktail.

Stein work is laden with images that provide direction and diction. Hoagland notes that “image is an elegant constituent of the speaker’s voice” (69) and Stein uses image to full advantage. In “After she told me she was pregnant” Stein opens with “The body kept bobbing /to the surface so I slid her under the ice” (19). This is a very seductive yet visceral image. The speaker holding the body down ultimately learns that the words were a lie “which I only found out later,/ once it was over, and then/ I had a lifetime to think about it” (19). Her word choices here place emphasis on hard sounds, “body” “bobbing” “rinsing the blood,” “rinsing the lie” “bubbles collecting” “embedded,” and we can see this scene unfold.

In “Annunciation” the image of “cherries hemorrhage” (34) and “dough bloat” (34) ultimately set the stage for “Husband’s home” (34) and “forehead bruising/ bleached linoleum” (34). The images start and support the scene that is about to unfold. The stop is “An angel’s burning/ hands hold down her shoulders” (34), but the sounds of the language have remained constant, with “b’s” and “h’s.” This may explain why the stop/start of her poems is so effective. The sounds do not create the stop, the words do. There is violence, passion, redemption and possibility or as Doty notes “dangerous sweetness” (xii).

***

Works Cited:

Hoagland, Tony. Real sofistikashun: Essays on Poetry and Craft. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2006. Print.

Karp, Evan. “The Write Stuff: Melissa Stein on the Literary Mood Swing” SF Blog. n.d. web July 27, 2013.

Stein, Melissa. Rough Honey. Philadelphia: The American Poetry Review, 2010. Print.

Stein, Melissa. “Rain.” American Academy of Poets. n.d. web July 25, 2013.

Stein, Melissa. “Bio.” Melissa Stein. n.d. web July 25, 2013.

***

Susan B. Gilbert is a poet/educator, very much at home in San Pedro, CA. Recent poems have appeared in Written River: a journal of eco-poetics, Sugar Mule, and LA Yoga. Her chapbook, Blue White Veil, (2012, Black Bamboo Press) is available through Amazon or on her website: http://www.bluewhiteveil.com/.

Tags: Melissa Stein, Rough Honey, Susan B. Gilbert