The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am

The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am

By Kjersti A. Skomsvold

Translated by Kerri A. Pierce

Dalkey Archive Press, 2011

147 pages / $17.95 Buy from Dalkey

Originally published in Norwegian as Jo Fortere Jeg GÂr, Jo Mindre Er Jeg by Forlaget Oktober A/S, 2009

Although I know I shouldn’t, sometimes I judge a book by its title.

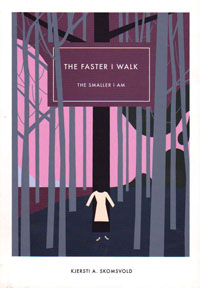

At first glance, The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am might suggest some kind of self-help manual advocating weight loss by means of low-intensity cardiovascular exercise. But putting the title aside and judging instead from the book’s front cover, (something else I know I shouldn’t do,) it’s clear this could never turn out to be the case. The copy I have, the hardback Dalkey Archive Press 2011 translation, sports artwork reminiscent of a Marcel Dzama painting. In a forest of leafless trees against pink-purple sky there is a woman standing with her back to a trunk, iniscernible save for her white dress and white shoes. The woman turns out to be Mathea Martinsen, and the title turns out to be a reference to Einstein’s theory of relativity, and the book’s content turns out to be a candid portrayal of losses far greater than that of a few inches around the waistline.

Skomsvold writes from the point of view of the front cover’s indiscernible woman. Mathea is childless, widowed and “almost a hundred, just a stone’s throw away.” All of her life, she’s been overlooked. “The spun bottle never pointed at me, the neighborhood kids never found me when we played hide-and-seek, and I never found the almond in the pudding at Christmas…” Now she lives alone in the same apartment block in Haugerud, a suburb of Oslo, where she has spent all her married life. Mathea likes to knit ear-warmers, read the obituaries and start new rolls of toilet paper. She is surprisingly proud, yet appallingly lonely – so lonely she listens to the distant sound of sirens and wishes they were coming for her, so lonely her only sense of fellowship is achieved by buying the same groceries as strangers she passes in the aisles of the local store.

The 147 pages of Mathea’s story commence somewhere in the aftermath of her husband’s death and with the subsequent realisation of how little her own life has amounted to. “I didn’t do nearly enough,” she says, “and nothing mattered anyway.” She resolves to try making some kind of impact, howsoever pathetic, before it is too late. The problem is that Mathea is disproportionately afraid of the world– so afraid she’d rather let all of her teeth fall out than phone up for a dental appointment, so afraid she has to muster all of her courage just to stop and read the fliers on the apartment compound’s community bulletin board. “I’m just as afraid of living as I am of dying.” She says, and so it takes colossal effort even to accomplish the most unspectacular of tasks – to start a conversation with a dim-witted man standing in a clump of bushes, to bury a time-capsule in the apartment compound‘s front lawn, to shop-lift two tubes of strawberry jam from the grocery store – all to little effect.

The greatest loss portrayed within The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am is that of opportunity. On the very second page, Mathea says, “I’m wishing I could save what little I have left of my life until I know exactly what to do with it.” But of course, she can’t. And so, of course, I know right from the offset that even in spite of the indiscernible woman’s most constructive intentions, things are unlikely to turn out well.

Although I know I shouldn‘t, sometimes I judge a book by the author’s photograph where it appears miniaturised somewhere between the cover blurbs.

I find Kjersti A. Skomsvold inside a French flap. She is intimidatingly beautiful – the finely boned and nicely symmetrical features which are supposedly quite typical in Scandinavia. The first thing I think, somewhat begrudgingly, is how can someone so young and pretty possibly write authentically in the voice of a character so old and toothless, so wretched and lonely? Surely great literature can only arise from a horrible life, and surely a horrible life is always best displayed by means of a particularly horrible face?

Nonetheless, one of the book’s most striking aspects is the unswerving distinctiveness of the old lady’s voice which never once slips out of Mathea and back into Kjersti. The innate sincerity of Skomsvold’s narration doesn’t quite make sense until I stumble across a transcription of the author’s opening remarks given at a panel discussion on ‘Loneliness and Community’ at the PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature last spring. “My plan in life was to be a computer engineer, and for some years all the writing I did was in programming language. Fortunately life doesn’t always turn out the way we plan.” Skomsvold says. “And maybe all we want in life is a sorrow so big that it forces us to become ourselves before we die.”

She goes on to explain something of the circumstances which finally breathed life to her inner-Mathea. “I got ill, and I had to move home to my parents and live in their basement.” Further on, she says “I didn’t have studies, friends, a boyfriend, or any of the activities I used to have to define myself.” And then further again, “I’m glad I didn’t know how hard it is to write something of quality, because then I probably never would have tried.”[1] And so the book was gradually pieced together from two year’s worth of post-its stuck above Skomsvold’s sick bed, from thoughts about infirmity and solitude and death.

Although I know I shouldn’t, once I’m done judging a book by title, cover and author’s face, I’m inclined to judge it by the yardstick of whatever else I might happen to be reading simultaneously.

What this means for The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am is a Chekov story entitled Gooseberries in which Ivan Ivanych, an aging veterinary surgeon, shares a fable with some friends in a lamp-lit drawing room one rainy night. There comes a point at which he says, “It’s obvious that the contented person only feels good because those who are unhappy bear their burden in silence; without that silence happiness would be inconceivable. It’s a collective hypnosis. There ought to be someone with a little hammer outside the door of every contented, happy person, constantly tapping away to remind him that there are unhappy people in the world, and that however happy he may be, sooner or later life will show its claws; misfortune will strike – illness, poverty, loss – and no one will be there to see or hear it, just as they now cannot see or hear others. But there is no person with a little hammer; happy people are wrapped up in their own lives, and the minor problems of life affect them only slightly, like aspen leaves in a breeze, and everything is just fine.” I’m sure plenty of Chekov scholars have already pointed this out, but the way I see it is that the writer himself was the person with the little hammer. Through his stories, without preaching or creating caricatures, he brought to light the unacknowledged difficulties and veiled sorrows of society’s malcontent. And now here is Skomsvold, despite the drastic shift in era and situation, carrying on Chekov’s great modern literary tradition of ‘tapping away’. And here is Mathea Martinsen as the unhappy embodiment of all those still bearing their burdensome silences.

Nearing the end of Gooseberries, Ivan Ivanych declares that “Happiness does not exist and it should not exist, and if there is a meaning and purpose to life, then that meaning and purpose is certainly not for us to be happy, but something far greater and wiser.”[2] As soon as I read that, I thought of a Mathea equivalent – I thought of the last conversation she forces herself to have with the dim-witted man in his clump of bushes. “Who said life’s supposed to be good?” He says. “Isn’t life supposed to be good?” She says. “No,” he says. “It’s supposed to be hard.”

The book ends about eight pages later, (and although I know I shouldn’t judge a book by its ending,) it’s a good end.

Then, in the aftermath of finishing The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am and in the daily process of performing all those inane little tasks so hideously necessary for continued survival – washing up, brushing teeth, tying shoelaces, buying cheese – I find myself thinking of Mathea. Whenever I flick past the obituaries page in the newspaper or go to start a new roll of toilet paper, Skomsvold comes at me with her little hammer and I begin to understand that little hammers are probably the best way to judge books after all – by the subtleties of how they come back to haunt me, by the small changes they make to the way in which I move so thoughtlessly through the world.

***

[1] All quotes from Kjersti A. Skomsvold’s opening remarks at the panel discussion on ‘Loneliness and Community’ given at the PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature 2011 were taken from a transcription she shared with The Mantle: a forum for progressive critique and which may be found in full at http://mantlethought.org/content/pen-2011-remarks-loneliness-and-writing-kjersti-skomsvold

[2] Both quotes from Gooseberries by Anton Chekov from About Love and Other Stories: A new translation by Rosamund Bartlett first published by Oxford University Press in 2004, reissued in 2008

***

Sara Baume is a writer, of sorts. Her reviews, interviews, articles and stories are published occasionally both online and in print. She lives on the south coast of Ireland and can be found at

www.sarabaume.wordpress.com.

Tags: Dalkey, Dalkey Archive, Kjersti A. Skomsvold, Sara Baume, The Faster I Walk The Smaller I Am

I’d been curious about this book. This insightful review has now pushed it to the top of my list.

[…] toothless, so wretched and lonely?»Baume ender likevel opp med å komme over fordommene sine. Les hele anmeldelsen her.*I juli skrev jeg om å ha hørt New York Review og Books redaktør Robert B. Silvers snakke i […]