It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers

It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers

Ed. by Lisa Pearson

Siglio Press, May 2011

292 pages / $45 Buy from Siglio or Amazon

Disclosure: I am a former intern at Siglio who helped produce this book back in 2010. I am close to it, but not too close. That is to say I had no idea what I was signing up for and had little to no knowledge of most of the contributors until I began copyediting their words for publication. That said, the process of helping make the book gave me an opportunity to learn more about art, narrative, feminism, and women’s studies, and who couldn’t use more of an education in any of those categories? At first I wasn’t even sure what image+text work was, but it encompasses forms of art—installation, photography, drawing, painting, video, etc.—that utilize language, like writing on top of a photograph, often to create narrative instability. There is a lot of solidarity between image+text work and conceptual writing, and they can denote the same thing (more on that later). I’m hoping my minor involvement with this book can translate into a wider conversation about the relationship between image+text work and conceptual writing, especially coming off the heels of the release of I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women (Les Figues Press, April 2012).

***

An exemplification of its mission to publish uncommon books that “live at the intersection of art & literature,” Siglio’s It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers (hereafter referred to as ITAT for short) reads like a riot grrrl literary arts mix-tape: nearly 300 pages of carefully reproduced text, photo, collage, sculpture, early computer print-outs, graphic notations, maquettes for slide projection, and more, of 28+ image+text artists from across the globe. Designed as a wunderkammer, this is not an anthology but an eclectic collection, “ungoverned by chronology, an alphabet, or a list of subjects,” says the editor Lisa Pearson in her afterword. Instead, the sequencing is structured so that “conversations” can emerge between the works themselves, yielding many narrative possibilities. In laymen’s terms, it’s fun to flip through.

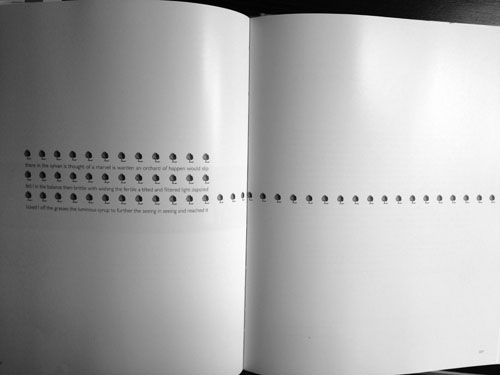

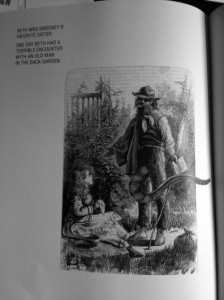

Every time I open it I see a new connection. Take, for instance, the way the graphic illustration of Shari DeGraw’s line of little trees on pages 226-227 weaves into Ann Hamilton’s concordance on page 230 with subtle continuity (see picture below). Another thread is the durational quality of certain artworks, such as Eleanor Antin’s “Domestic Peace,” a notational map of conversations carried on with her mother for 17 days, and Susan Hiller’s “Ten Months,” which photographically tracks her stomach as it grows during pregnancy, depicting “a means of making actual what is potential” (175). Much of the included art dates from the 70’s, a major decade of feminist art, when many artists boldly challenged misogynistic attitudes towards the female body. A section from Cozette de Charmoy’s 1973 “The True Life of Sweeney Todd,” which collages reptilian parts in less than appropriate ways onto illustrations from the 19th century Illustrated London News, offers a perverse sense of anatomy augmented by unusual devices. The more recent work of the 1990’s has a formalistic remove from bodily exhibition, suggesting an aesthetic turn towards abstraction over confrontation.

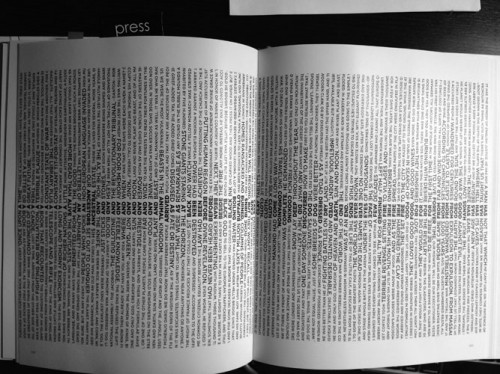

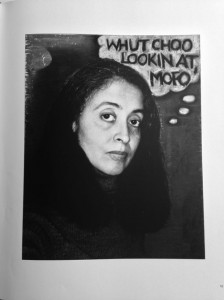

Adrian Piper’s 1979-1981 “Political Self-Portraits” mischievously opens the collection by framing the direct gaze of a bi-racial face to challenge our epistemology of sight (how we judge race based on skin tone). The self-portraits’ charged captioning—self-portrait exaggerating my negroid features—appear as a more personal antecedent to Barbara Kruger’s scandalizing text installations of the 80’s. By contrast, Fiona Banner’s meta-novel “The Nam” and Molly Springfield’s photorealistic drawings of translations of Swann’s Way (this double remove intentional), highlight “the materiality of language” craze of the 90’s brought about by Derrida. These two works foreground the techne of reproduction over the originality of the content, redefining the concept of authorship.

Overall ITAT creates a rich correspondence between hybrid strategies of aesthetic representation and the politics of feminism. Subjectivity is heternormative. In her awesome review of the book at The Poetry Foundation, Eileen Myles writes, “because the frame is image + text we’re reminded that all of us generally do more. Female artists don’t just stay in their disciplines; we experience, we forage, we play.” Thinking beyond binaries of gender, race, and sexual orientation, requires more than one medium, one language, one identity. This might sound pedantic but I’m talking about people’s skin:

And I think Adrian’s question here is partly rhetorical, meant to sound ‘black’, but it is also open-ended, an invitation: what are we looking at? Someone of mixed race, and that troubling distance she maintains from the spectacle of her body, citing it while slipping from the myths of racial purity, relies upon imagery as much as language, like a comic book, only more Kantian. I like how this piece opens the book because of its invitational (if confrontational) tone, that it asks you in, and that throughout the book one is not so much reading the book as reading between the lines, so as to see, in the case of Piper, her racial difference. Each page nearly letter-sized and glossy, there is capacious room for the details to pop. Bottom line: this book would be allowed to hang out on your coffee table.

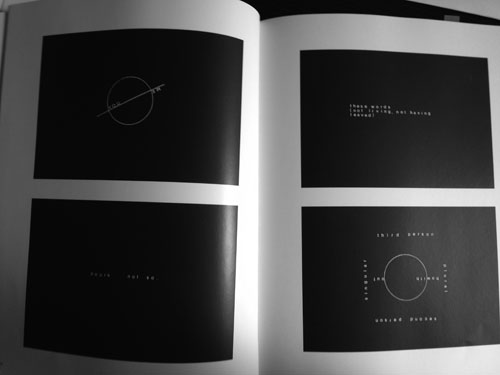

It is in the nonrelation to self that each artwork reaches an idea of beauty not in contradiction with the body. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s titular piece, composed of strings and circles of bounded pronounal units intersecting, pressures how language territorializes identity. The engulfing blackness around the text-shapes lends them an extreme fragility, a tender distance, a politicized silence. That Pearson dedicates around ten pages to each contributor allows space for their art to breathe.

In solidarity, Les Figues Press recently released the groundbreaking anthology, I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, which has significant overlap with ITAT (both feature Bernadette Mayer, Bhanu Kapil, Hannah Weiner, and Theresa Cha) and so makes an excellent companion. While centered more around textual poetics than visual art, it also plays with narrative multiplicity, female mimicry, and political passion in very complementary ways. The baroque structure of I’ll Drown My Book’s organization, which is divided into Process, Structure, Matter, and Event, with subsets to each and lots of introductions, differs from Siglio’s introverted editorial process, which Pearson describes in her afterword:

“A survey of any kind seemed to me not only impossible but anathema to the nature of the work itself. In the beginning, it became clear that the selection would have to be driven by an act of collection rather than that of anthologizing. In other words, I would not be looking for works that could be arranged inside a set of categories of any kind; rather, I would be adding and subtracting as interesting relationships between the works evolved” (281)

To which Laynie Browne in her introduction to I’ll Drown My Book replies:

“We have chosen terms for classification with the intent to encourage inquiry rather than to stipulate” (14)

It is interesting to think about the difference between anthologizing and collecting. Should the relationship between works in a book be categorical or fluid, programmatic or polysemic? Perhaps the distinction is analogous to determining whether Mondrian’s grids read in a centripetal or centrifugal fashion—an ambiguity always remains.

One of my favorite discoveries from ITAT is little-known German surrealist artist Unica Zurn, from “The House of Illnesses” (1958). Composed during a bout of jaundiced fever, the narrator, an institutionalized mental patient, speaks with existential lucidity so grave I compare it to Camus. Written in the form of manic diary entries, here’s how she opens with Tuesday: “People have always been divided into two groups: victims and murderers. I don’t know whether it is possible to free oneself from one group and switch over to the other during one’s life. I at least have not yet managed to become a murderer. It’s my fate to be an eternal victim” (211). One can only imagine what happens on Wednesday.

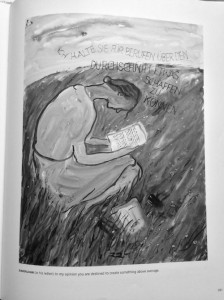

I also find the concluding work of Charlotte Salomon, a German Jew who died at Auschwitz, particularly touching. This is no doubt because the gentleness of her brush stroke is so tragically at odds with the brutality of history. A long graphic novel intended as a Gesamtwerk with musical accompaniment, “Life? Or Theater? A Song Play,” tells the multigenerational story of her family’s Weimar era history. The chapter excerpted is about young Charlotte falling in love with her music teacher. It feels uplifting and heartbreaking at the same time. In one dialogue he says after examining her paintings, “My discovery of the similarity between what young girls produce and what certain geniuses produce is completely justified” (273). Touché. Consider this collection more proof.

***

Nicky Tiso is an MFA creative writing student at The University of Minnesota. He received his BA from The Evergreen State College in 2010, and interned with Siglio Press inbetween. His work has been published online in: Poets for Living Waters, Tarpaulin Sky, HTML Giant, Ditch, Thieves Jargon, No Record Press, and Wheelhouse Magazine. A recipient of the 2012 Academy of American Poets James Wright Prize for Poetry, judged by Garrison Keillor, he was also a panelist at the 2013 Conference on Ecopoetics at UC Berkeley, and blogs infrequently at nickytiso.blogspot.com. His manuscript is currently up for auction.

Tags: It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers, Lisa Pearson, Nicky Tiso, Siglio

I am reviewing this for RCF. Thanks for the good read.