Down These Mean Streets

Down These Mean Streets

by Piri Thomas

First published 1967, Knopf.

Vintage Edition, 1997

352 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon

In the essay “The Simple Art of Murder” for The Atlantic Monthly in 1945, noir author Raymond Chandler wrote “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.” While Chandler was speaking about detectives in novels, the same could easily be said about youth growing up in inner city neighborhoods. The first person publicly known to make the connection was Knopf editor Angus Cameron, who paraphrased this on a manuscript he was given titled “Home Sweet Harlem” by a man named Piri Thomas. The manuscript, which was published by Knopf in 1967, would become known as Down These Mean Streets.

In May of that year, critic Daniel Stern of The New York Times reviewed the memoir, saying, “It is something of a linguistic event. Gutter language, Spanish imagery and personal poets…mingle into a kind of individual statement that has very much its own sound…” Little did Stern realize that so-called “gutter language” would have such an impact on contemporary literature. Subsequently the novel was later banned in multiple school districts across the country (including District 25 in Queens, New York) on the basis of obscenity.

The ban in Queens was not lifted until five years later, even after it was brought to court by the New York Civil Liberties Union.

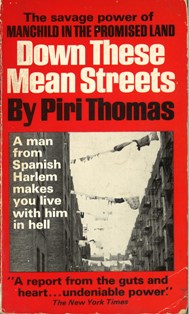

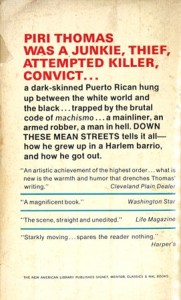

Published several years after Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land, (which unlike Thomas’ memoir is an autobiographical novel) the book was marketed using language akin to the sensationalism of most modern tabloids, as any reader can see on the front and back covers of Signet’s 1968 reprint. Phrases such as “savage power” and “the brutal code of machismo” plainly indicate a widespread culture of ignorance. Thus was the attitude of publishers about works based on the experiences of people of color in 1968. Whether much has changed in the publishing industry’s attitudes about urban literature now is an entirely different discussion.

Down These Mean Streets is divided into eight sections, which chronicle Thomas’ childhood in Spanish Harlem, his family’s move to Long Island, his times as a heroin addict, Merchant Marine and armed robber, all the way through his period of incarceration and life upon release. This structure gives the book an episodic feel, allowing readers to easily pick up from where they left off, while the narration has a colloquial quality. During one scene, Thomas recounts a bodega robbery gone bad as a young teen:

“I could imagine the fuzz shining their flashlights through that store door, and digging the smokes all over the floor and the cash drawers open. I could see them making it to the back window, digging the pried-out bars. Right about now they’d be cruising the area looking for suspicious-looking cats like us.”

Besides its vivid depictions of scenes, from summer streets, alleys and rooftops in El Barrio to the Tombs and Sing Sing Prison, Thomas proves he has a gift for parroting those he grew up with through dialogue, particularly in his use of Spanglish. (The 1968 Signet first edition had a glossary for non-Spanish speaking readers.)

While Thomas as narrator constantly speaks of trying to escape the neighborhood he grew up in, he also returns again and again. One of the larger themes besides poverty, violence and the culture of machismo is the issue of racial identity as a light-skinned Puerto Rican. Besides the memoir being one of the first major works of literature by a Nuyorican to be recognized by the mainstream publishing industry, the issue of racial identity is one of the main reasons why the book should continue to be studied in 2012.

Thomas’ memoir may have been written during Johnson’s War on Poverty, but as Thomas explains in the afterword to the 30th anniversary edition:

“The sad truth is that people caught in the ghettoes have not made much progress, and in fact, have moved backwards in many respects—the social safety net is much weaker now. Unfortunately, it’s the same old Mean Streets, only worse.”

And now, 15 years later, the social safety net has continued to deteriorate. Thomas passed away last year, at the age of 83, decades after many of his childhood friends. While some may say that Americans have moved passed racism, Thomas’ memoir in its depiction of institutional racism, confused identity and struggle into manhood is as, if not more relevant than ever.

***

Eric Nelson came of age in both the concrete jungles and Pine Barrens of New Jersey. Nelson’s non-fiction and journalism has appeared in or is forthcoming in chimes/SIRENS, The Billfold, Electric Literature and Bushwick Daily. His fiction has appeared in Squawk Back, Volume 1 Brooklyn and Having a Whiskey Coke With You and his book of short

stories, The Silk City Series, was published by Knickerbocker Circus in 2010. He co-curates the Fireside Follies reading series in Brooklyn.

Tags: Down These Mean Streets, Eric Nelson, Piri Thomas