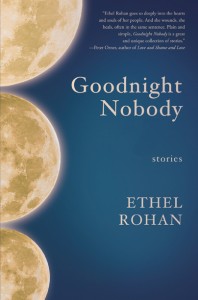

Goodnight Nobody

Goodnight Nobody

Goodnight Nobody

by Ethel Rohan

Queen’s Ferry Press, September 2013

138 pages

Phantom pains are a phenomena in which the patient suffers pain in a limb that is no longer part of the body. In Ethel Rohan’s Goodnight Nobody, symbolic phantom pains abound and absence makes the longing for completion more keen. There is a subdued humanity in each of the thirty stories that mix melancholy and joy with a sense of loneliness. In “The Splitting Image,” twin boys are identical apart from a missing arm on one. Despite their mirrored images, their personalities could not be more different. This disparity becomes a schism symbolized by the absent arm. One brother wants a whole arm to be complete while the other wishes his brother would “take it. Just fucking take it.” Unfortunately, it’s neither his to give nor his brother’s to take, and both are stuck as they are.

Likewise, thirteen-year-old Esther has lost her grandfather to spontaneous combustion in “Out of the Ashes.” Speculations from those around them run rampant, including ones that his death had something to do with supernatural forces. All the talk has her disconcerted and her mother has taken it hardest, verbally exploding at someone who asks about the cryptic nature of his death. Esther is helpless to act and wonders if her grandpa truly had made some type of sinister deal. The threat of such a possibility scares her and her sense of alienation is emphasized by the burn of the sun.

There’s an organic melding of themes and the obsessions the characters wield in many of the stories. In “Bee Killer,” the disconnect between a husband and wife is represented by a hive of bees the husband maintains. The emotional gulf between them is both grand and dwindling, difficult to articulate and yet swarming with stinging malcontent. He seems more concerned with the bees than her well being. It’s the quiet discontents that add up and eventually overwhelm:

“What about the queen?” I said. “The colony would be nothing without the queen.”

“She’s as much a slave to duty as the rest,” he said. “Average queen lays two million eggs in her lifetime.” He went on to tell me how a sick bee leaves the colony to die alone, so as not to infect the others. “Sacrifices himself,” he said.

“Plenty of us do that,” I said.

A photographer from “Darkroom” is going blind from a condition that is both “genetic and degenerative.” Fueled by her pending blindness, she wants to capture “the photograph of a lifetime.” The permanence of the camera becomes a substitute for the deterioration in her eyes and the visibility that will soon escape her. Capturing an image of the giraffe becomes the specific target and she goes on an adventure with her husband to get it. It seems foolhardy, until we realize it’s her way of warding off the inevitability of permanent darkness:

“I wish the blindness would just come and take my eyes right now.” Her voice shook and she held herself. “I hate the waiting.”

He pulled her into his arms and hid his tears in her hair, seeing those zoo elephants from so long ago and remembering the tickle of the animal’s trunk on his palm and the side of his face, its breath warm and pleasant, but searching, searching.

All of Rohan’s characters search for things they can’t have and the prose is elegantly wrought, neither excessively sentimental nor overtly flashy. Instead, there is a lush rhythm in the sentences that renders observations in natural beats. Judgment is suppressed in favor of an understanding of the complexities of friendship and family, however quaint or unusual. Irish settings for many of the stories act as a unique brogue against the landscape of the collection. Everyone is drifting, flotsam from the shipwreck of modern conjunctions. The shorter length of many of the stories make them seem like splices from a bigger sampling, a gauge on the tempo of a bigger macrocosm.

August 2nd, 2013 / 11:00 am