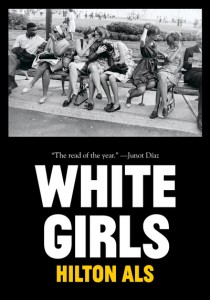

White Girls by Hilton Als

White Girls

White Girls

by Hilton Als

McSweeney’s, Nov 2013

344 pages / $24 Buy from McSweeney’s or Amazon

White Girls ends with the essay “It Will Soon Be Here,” a meditative consideration of memory and the flexibility of first person. The essay could prefigure the entire collection by Hilton Als: “For as long as my memory can remember, I existed characterless, within no memory at all. Or if I did exist it was in remembering the text of someone else’s life—that is in the devouring of biography.” That which is devoured must soon be released, and Als does so in White Girls, covering Truman Capote, Eminem, Richard Pryor, Malcolm X, André Leon Talley, James Baldwin, Flannery O’Connor, and Als himself. Early critical mentions of this book as controversial not only miss the point (idiom Als uses effectively on many occasions regarding the misunderstanding of other persons and writers), but fail to recognize that Als has been building toward this book since The Women (1998). White Girls is pure performance, a writer in absolute control.

In “A Pryor Love,” Als’s wide-ranging essay on the comedian, he notes that “unlike Lenny Bruce, [Pryor] didn’t believe that if you said a word over and over again it would lose its meaning.” The same could be said of “white girls,” or “white women,” which are flashed by Als like a card, a refrain, a reminder. In a scene within “The Only One,” Als’s sketch of Vogue editor Talley, a “black drag queen . . . sat on the lap of a bespectacled older white man,” and said “That’s what I want you to make me feel like, baby, a white woman.” For Als, being or becoming white is not quite an assimilation into difference, it is an act of twinning. White Girls begins with the nearly 100 page nonfiction novella, “Tristes Tropiques,” that documents Als’s complicated love for SL (“Sir or Lady”), who is first described in the midst of a daydream. It would be quite dangerous to read White Girls in full-on mimetic mode; the book starts, after all, with Als imagining SL “deep in movie love,” thinking about SL’s own thoughts, when the “movie guy kisses the movie girl and they are one.” This trope of twinning becomes an anchor for not only the relationship between Als and SL, but also the other loves of Als. Also loves SL, but they “are not lovers. It’s almost as if I dreamed him—my lovely twin, the same me, only different.” There are levels and modes of twins. Als recognizes the idea of a mirror, that other that is the self, but also the opportunity to “grow into one . . . as Aristophanes sort of has it in The Symposium.” Twinship, for both SL and Als, is the “archetype for closeness . . . [and for] difference.” Twinship is “marriage . . . joined by a ring and flesh.” It is “reflection.” The origin of this desire? “I have always been one half of a whole,” Als admits. An older brother was stillborn; “my ghostly twin, my nearly perfect other half.” His mother is his “soul’s twin.” For Als, all love is a form of self-completion, the discovery that the “I” needs a second to live.

I am the father of identical twin girls, so I breathe this world of twins. The moments of mistaken identity, the calling of incorrect names. My wife—she my twin, of sorts, us together and inseparable for a dozen years now—pass our twins (Amelia and Olivia) back and forth, their identities switching with each shifting hands. For twins, the collective is not pejorative. “I” becomes wide. Als finds this ultimate twinship in SL, for they lived parallel lives, not quite in biography but in gesture, as they “had both grown up feeling that the language we spoke was somehow incomprehensible or fuzzy to those around us.” Yet SL was not Als’s first twin love; that was Marie, a white girl who “wasn’t technically white—her mother was Puerto-Rican and her father Jewish—but she looked the part: camellia-white skin and blonde hair.” Als’s prose, in her presence, is nothing short of sensual: “She alone could charge makeup at the family drugstore. I felt so much about her. She wore ropes of white beads a Santeria had given her. In her room: flickering candles, prayers for the dead, Santeria-blessed waters. Sometimes she sprinkled the waters on me. She made my soul happen.”

Yet Als arrives at the same question about Marie that the reader asks in relation to SL: “Did I love her or want to be her? Is there a difference?” He concludes: “I wanted her more than anything; her whiteness or, more accurately, her misleading whiteness—the blonde mistaken for a gringo by Latin men; the Jewish girl mistaken for a shiksa by Jewish men; a white girl mistaken for a white girl in my colored world—felt not unlike myself and not like myself all at the same time.” Even in this first essay, Als reveals his nuance, why he demands reading. White Girls could have been, in the hands of a novice, a smirking pastiche of all things pale. Als never simplifies: “standing above me and around me I see how we are all the same, that none of us are white women or black men; rather, we’re a series of mouths, and that every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savory, like love.”

The first essay alone is worth the price of the book, but Als delivers elsewhere. “The Women” begins with a photograph of Truman Capote, which is more “a shadow ground through publicity, coming out the other side as something else . . . asserting this: I am a woman.” Capote’s transformation into a woman, ultimately, “prevented other women authors from being popular, admired, celebrated.” Capote “saw women as a form of language.” Als might think the same of Michael Jackson. “Michael,” his elegy for the star, begins with a memory that his “female elders” would warn him of the men who leave the Starlite Lounge in Brooklyn. “Ben” is the theme song of those “queens,” and should be listened to on loop when reading this essay. Michael “was all child—an Ariel of the ghetto—whose appeal, certainly, to the habitués of places like the Starlite, lay partly in his ability to find metaphors to speak about his difference, and theirs.” Michael’s goal is to create an anti-twin; he “was most himself when he was someone other than himself.” He—or the idea of him—was representative of a particularly fearful type of influence, an example of the “bizarre fact that queerness reads, even to some black gay men themselves, as a kind of whiteness.”

November 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm