Author Spotlight

Exodus; an interview with Lars Iyer

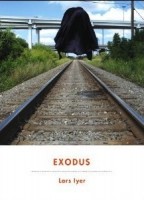

What Lars Iyer has managed to do in his trilogy, spanning from Spurious, through Dogma, and now to Exodus—the final book soon to be released from Melville House—feels rather unprecedented. At once these are individually these brilliant picaresque novels ambling through Europe and America; as well as idealistic conversational pieces between his protagonist, Lars, and his counterpart W. Perhaps my favorite aspect of Iyer’s work is the brilliant ways in which he’s able to meld the artists and thinkers of yore, with those today—weaving long conversations about Kafka seamlessly with those about filmmaker Bela Tarr. I’ve loved these novels, and watching them form an official trilogy has me ready to start right over reading them, or anxiously await Iyer’s next effort. I had the opportunity to ask Lars Iyer several questions upon the release of Exodus. We discussed many things, from Nietzsche to Pasolini, and Iyer was prolific in his responses.

What Lars Iyer has managed to do in his trilogy, spanning from Spurious, through Dogma, and now to Exodus—the final book soon to be released from Melville House—feels rather unprecedented. At once these are individually these brilliant picaresque novels ambling through Europe and America; as well as idealistic conversational pieces between his protagonist, Lars, and his counterpart W. Perhaps my favorite aspect of Iyer’s work is the brilliant ways in which he’s able to meld the artists and thinkers of yore, with those today—weaving long conversations about Kafka seamlessly with those about filmmaker Bela Tarr. I’ve loved these novels, and watching them form an official trilogy has me ready to start right over reading them, or anxiously await Iyer’s next effort. I had the opportunity to ask Lars Iyer several questions upon the release of Exodus. We discussed many things, from Nietzsche to Pasolini, and Iyer was prolific in his responses.

***

GM: When it was decided that this interview would happen, I went to check your blog for any updates and found the first entry to be an interview excerpt of Pasolini. Your work draws comparisons from fields far outside the immediate realm of literature—speaking here both of philosophers and filmmakers, comedians and old scribes—so I was wondering about the other side of things; as a writer, how do you address the taboo notion of influence? Do you see the influence of a filmmaker or philosopher as distinctly different than that of a write you greatly admire?

LI: You refer to quotations by Pasolini I excerpted on my blog. I put up quotations of this kind from all manner of sources – from film directors, artists, philosophers, writers and so on – anything I find intriguing, anything encouraging or ‘true’ in some sense. I quote from those I take to be allies – friends of a kind, who I imagine stand with me against common enemies. In this way, I try to spur myself on, especially during those dry periods when I can’t think of anything to write in my own name. The field of endeavour of those whom I quote are of little consequence in this regard – film, art, philosophy, literature – I’m looking only to be enlivened, for an axe to shatter my frozen sea.

How would I address the question of influence? One temptation, in speaking of the works of those who have meant most to you, is to give a narrative – of having read this and then that, of having incorporated this lesson and then that one – without considering how the texts in question transformed your methods of narration, and your ability to construct a coherent narrative regarding what was important to you. There is the risk of rendering linear and personal what is a much more complex reality, in which linearity and the very notion of the ‘personal’ are open to question.

Let me make this concrete. There was a time when lyrical works appealed to me, and lyrical ways of recasting your experience. So I wrote in a lyrical mode, of things that would allow of lyrical treatment. I took various lyrical writers as exemplars. As I grew older, overwhelmed by a world that seemed ill-fitted for such treatment, these modes seemed lifeless to me.

At that point, I found the writings of the European modernists grew more important. I felt that they, too, had run up against the world in a particular way. That they, too, were seeking less innocent ways in which to write, in which to narrate experience. I found the work of Blanchot of particular significance, especially his elusive notion of the narrative voice. I was fascinated by the way in which Blanchot, and the thinkers influenced by him, abandoned a certain linguistic personology, displacing the primacy of the first person in their account of literary writing. I was interested in the narrative modes they employed in their fiction and in other writings, where they showed how this personology failed when it came to rendering perfectly everyday experiences.

But even as the works of high modernism and modern continental thought absorbed my attention, I was conscious of living in a world very different from that of the thinkers and writers who interested me. The dilution of stocks of inherited culture; populism, and the dissolution of the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultural forms; a literary and artistic accommodation of capitalism and the marketplace; an intensification of the speed of communication; the transformation from a literary to a visual culture: I felt that all this, along with the cultural marginalisation and declining prestige of literary fiction, had to be marked in some way.

What mode of narration is appropriate to our own time?, I asked myself. What does it mean to be influenced by Blanchot and others like him, when writing in a British context? How could the narrative strategies of Blanchot influence a kind of fictional writing which would answer to a very different reality?

My concern, then, was not so much with the anxiety of influence as with the incongruity of influence – even the irrelevancy of influence. Because the thinkers and writers who influenced me, and who had addressed the issue of narration in such impressive depth, were nevertheless part of a culture in which literature still had a central role. They were part of another, older world, one that still had in place a real cultural security. They might have been critical of conventional modes of narration, but their work could still be considered as part of a set of literary and philosophical traditions.

The question of influence, for me, is therefore a significant one. If it does not make sense to produce a British version of Blanchot’s narrative voice, or to reinvent the nouveau roman in contemporary conditions, what can be done instead? If you do not belong to the same set of traditions as the thinkers and writers you admire – nor indeed to any particular tradition, what does this mean? For me, it was by marking the incongruity or irrelevance of influence in my writing that I found a way forward.

In these books I’d say you’ve managed to accomplish a sort of duo-protagonist narrative. Was this ever a distinct goal for you? Pairing Lars with W. results in much of the hilarity, and philosophical speculation along the way, but was there ever a notion that it might be Lars, or W. on his own?

Spurious, the novel, came out of Spurious, the blog, at which I found myself experimenting with many kinds of narrative techniques and voices, to accompany my engagement with Blanchot. The style of the W. and Lars material was a happy accident. It was foreshadowed, on the blog, by experiments in Bernhardian/Sebaldian-style indirect narration, and by dialogue-style autocritiques. But the first W. and Lars post was a stylistic step forward – one which I didn’t necessarily appreciate at the time, and which took several years for me to learn how to exploit.

I was busy, in the interim, trying to work in other styles of writing – in particular, first person modes of narration: Lars on his own. In this, I was strongly influenced by Blanchot, and worked hard. But I could never really bring this material alive, and wasn’t sure why. In the end, I think it was for the reasons I discussed earlier: there was an unbridgeable gap between my world, the world of contemporary Britain, and that of the thinkers and writers I admired. I needed to confront this gap, to turn it into a theme. I couldn’t satisfy myself with developing a new strategy of writing in the tradition of the European modernists, because my relationship to that tradition was broken. I drew, instead, on a very British comic tradition – a tradition so all-pervasive, so obvious, that it didn’t even stand out as a discrete tradition.

Whence the W. and Lars posts, with their intellectual slapstick, which echoes Withnail and I, Pete and Dud and so on … This humour is natural to me. It’s easy. It’s how I speak to my friends. It’s British; it’s true to contemporary Britain. It was by preserving the to-and-fro of such speech, as filtered through techniques of indirect narration and a jump-cut montage, that I gave to my material what it previously lacked: life.

The trilogy is essentially comic. But the formal structure of my ‘duo-protagonist’ narrative also lets me address the more serious question of the legacy or non-legacy of European philosophy, literature and politics in neoliberal Britain. Both characters show some awareness of the distance between their philosophical, literary and political enthusiasms, and the world in which they find themselves – W. less so than Lars, the narrator. By reporting the waxing and waning of W.’s passion for the modes of thinking and sense of political possibility that belonged to ‘Old Europe’, Lars creates a more intense sense of the distance between W.’s aspirations and the reality of his surroundings. There’s comedy in this, a very British comedy, but also a kind of tragedy. The narrative mode brings W. up against the horrors of neoliberal Britain.

In Dogma and, in particular, in Exodus, my ‘duo-protagonist’ narrative allows something else. We learn indirectly of many aspects of Lars’s life: his period of warehouse work, unemployment, squatting, his time with the monks, and so on. The mode of narration maintains a kind of mystery in respect of Lars, a kind of distance. In my mind, this mystery makes Lars a humorous British cousin of one of Blanchot’s narrators …

In another post on your site—a series of journals from William S. Burroughs—Burroughs describes the sensation of writing a new book (Naked Lunch, I believe) as essentially taking over his life. The writing of the book—something new, he asserts, something different from before—brings about changes within the book and it becomes something entirely new. When you’re writing, have you experienced things like this? Does the story take over? Are you planning things out for awhile before they present themselves as a possible book?

The dream of automatic writing – of allowing yourself to become, as Breton put it, a ‘modest recording instrument’ – is an enticing one. Burroughs, in Tangiers in the late 1950s, became exactly such an instrument – a kind of medium, a switch board. Burroughs bear witness to this. You can sense his excitement at what he was creating, at what, he felt, was being created through him. Burroughs undergoes a kind of dispossession – that lived relinquishment of linguistic personology that Blanchot and others write about. He inhabits his writing. This is the most enticing thing of all. Imagine being able to disappear into what you wrote, such that it seemed to bear you along with it! Imagine that your work had sufficient life of its own to carry you away with it!

For me, blogging offered the chance of the dispossession in question. There were no gatekeepers in the world of blogs; you could write what you liked, you could follow your whims, your interests, your obsessions, but there was still a minimal contact with an audience. And you could write alongside others with similar aims – you could be part of something, a fellowship of creators. I entered into blogging with an excitement similar to Burroughs’s in his Tangiers flat. A new medium had appeared, which invited a new way of writing: what a chance!

Over the years, I tried to produce a kind of magma of text, endlessly streaming. I dreamed of creating a million-word hyperlinked document, with theoretical elements, to be sure, but also non-theoretical ones, automatic ones, encompassing everything I had read, seen and experienced: a total book; my equivalent of Burroughs’s legendary ‘Word Hoard’. What hubris! But that’s what I set out to realise, returning home each night after work and opening a bottle of wine. I’m sure I achieved nothing of the sort! But I certainly experienced a Burroughs-like feeling of dispossession, albeit in my own way.

The novels came after this experience, after I’d left behind my older, blogging-friendly lifestyle. A good thing, too! And I had, by then, developed sense of most of the themes which continue to occupy me, and I had the W. and Lars material, which seemed ripe for development. But I’d lost a kind of innocence. Novels require a kind of work that blogging does not: a laborious process of revision, redrafting, and ordering of materials. You have to be very alert, very aware of what you are writing, and so lose that state of immersion which characterises more automatic forms of writing.

James Grauerholz recalls editing Burroughs’s The Place of Dead Roads, cutting out thousands of words of material, and reshaping the manuscript. Burroughs wrote, and Grauerholz, in consultation with Burroughs, shaped the material. Burroughs continued to pursue a kind of medium-like dispossession, channelling all kinds of experience, and Grauerholz undertook the hyper-conscious, audience-aware side of the editing process. Working on my novels, I have had to be both Burroughs and Grauerholz – in fact more often Grauerholz than Burroughs. In this sense, the ‘story’ never really has time to take over. You’re always interrupting yourself, reshaping your material.

Of course, the aim would be to be able to edit yourself as you write. To merge Grauerholz and Burroughs into one. D.H. Lawrence was able to train himself to write more and more rapidly. Instead of tinkering with the manuscript of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he wrote it afresh, all over again – and then once more. I remember him using the expression, ‘a fresh gesture of creation’. To be capable of such freshness! To write like Muriel Spark did, or Duras, finishing a manuscript by writing straight through in a matter of weeks! But I’m a long way from that …

I was recently listening to an interview with Edward St. Aubyn, in which he discusses writing the first three Patrick Melrose novels as a trilogy that stands alone, then suddenly he began writing more and felt two or three more books tie themselves to the original three. Do you see this as a possibility or is Exodus the end for Lars and W.?

I was recently listening to an interview with Edward St. Aubyn, in which he discusses writing the first three Patrick Melrose novels as a trilogy that stands alone, then suddenly he began writing more and felt two or three more books tie themselves to the original three. Do you see this as a possibility or is Exodus the end for Lars and W.?

Exodus is the end for the characters, for now. I think of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra as a terrible warning. The first three parts of it build on one another in the most exciting of ways, but the fourth part, written at an interval after the first three, is dreadful!

What sort of complications/benefits come from a prolonged narrative like a trilogy? As the author was there anything surprising or significant to come about as the writing developed?

In his multi-volume Book of the New Sun, Gene Wolfe has his narrator return to the same scenes over and again, granting them, with each iteration, a fuller and deeper rendering. This is something that writing my trilogy has permitted – tackling Lars’s years in the warehouse, his encounter with Kafka, more than once. I must admit, I would like to do something similar with my account of Lars’s Manchester years in Exodus, or even with an event as fleeting as W. and Lars’s encounter with the madman on the London Underground. But the warning of Thus Spoke Zarathustra still holds!

One question that nagged me reading all three books, how does the notion of a ‘philosophical novel’ strike you?

I suppose a philosophical novel is one which explicitly tackles certain philosophical themes. Philip K. Dick’s novels are exemplary in this case, as they explore the nature of reality, of subjective experience, and so on. But more broadly, I suppose the writing of many kinds of literary novel implies what Lawrence called a ‘metaphysic’ – that is, some kind of philosophical framework. Lawrence himself is an example – think of his ‘Study of Thomas Hardy’, or ‘The Crown’, which inform his writing of The Rainbow and Women in Love respectively. Of course a writer doesn’t need to be as explicit as Lawrence! Wittgenstein was, I think, right to complain about the explicit philosophizing of the kind you find in Tolstoy’s War and Peace, when compared to the implicit philosophical work of Tolstoy’s later tales.

The question in my novel-writing was how to mark the distance between the philosophical concerns of the characters and the world in which they live. This may seem to be a meta-philosophical aim, exploring the difficulties of living in accordance with the philosophy of another time. But philosophers have always been concerned with these kinds of difficulties. That’s what you find, e.g., in applied ethics, where it is often a question of asking how the work of Aristotle or Kant – philosophers from very different periods – might illuminate a contemporary ethical issue.

With the novels, there is, of course, much comic potential in juxtaposing the characters’ interest in Kierkegaard with their more petty concerns. But that comedy – that kind of juxtaposition – is also present in Kierkegaard’s work. I wonder if there really might be a comic, fictional way of doing philosophy, and not just reflecting on philosophical themes …

The title ‘philosopher’ is one typically bestowed upon you. With characters like Slavoj Zizek and co., I was wondering what you thought the role of philosopher might come to be in the twenty-first century, or if you had any thought in this general arena?

I include Žižek, Badiou and Mladen Dolar as characters in Exodus. They are exemplars, for W. and Lars, of what modern philosophy should be, being passionately concerned both with their abstract philosophical work and with engaging with political issues in the world, barely acknowledging a difference between these concerns. This is deeply impressive to me! In my view, the necessity of the critique of neoliberalism means philosophy is as important as it has ever been.

***

Grant Maierhofer is the author of Ode to a Vincent Gallo Nightingale, he blogs at miredingriefmiredingrief.com and lives in the middle of nowhere in Wisconsin.

Tags: dogma, Exodus, Grant Maierhofer, Lars Iyer, Spurious

[…] HTML Giant interviewed Lars Iyer, whose Exodus is out now from Melville House. […]

[…] Exodus, an interview with Lars Iyer @ HTMLGIANT […]

[…] September 2nd by Melville House.” And I cannot fucking wait. I had the immense pleasure of interviewing Iyer at one point about his previous trilogy of novels, and I’m convinced he’s one of […]