October 20th, 2010 / 11:03 am

Author Spotlight

Catherine Lacey

Author Spotlight

Interview: Stephen O’Connor

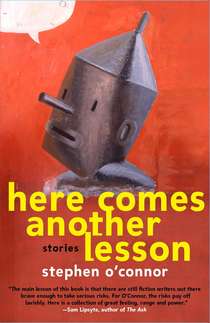

I don’t know why you don’t already know and love Stephen O’Connor. He has never before been mentioned on this blog and for that I am trying to make amends. He’s published two collections of fiction and two works of nonfiction and the most recent is Here Comes Another Lesson, a collection of short stories that will just split you open in so many ways.

I don’t know why you don’t already know and love Stephen O’Connor. He has never before been mentioned on this blog and for that I am trying to make amends. He’s published two collections of fiction and two works of nonfiction and the most recent is Here Comes Another Lesson, a collection of short stories that will just split you open in so many ways.Here, go read his story “Ziggarut.” It was in The New Yorker but it’s completely unlike your typical New Yorker story– the main character is a Minotaur and, well, you should just read it. The interview below was conducted over email a week ago.

Catherine: What one attribute (or attributes) do most (or all) of the characters in Here Comes Another Lesson have in common? (Feel free to answer this question by inverting it.)

Stephen: One of the things that has most disconcerted me about my books is that almost everything I have written — fiction or nonfiction, realistic or not — tells the same story about a character who tries to do the right thing and fails. In my memoir about teaching in the public schools, Will My Name Be Shouted?, I am that character. In Orphan Trains, a nonfiction account of a controversial 19th century child welfare effort, Charles Loring Brace is that character. But this character also appears over and over again in Here Comes Another Lesson, just as he (or she) also did in my first collection, Rescue. He’s the Minotaur in “Ziggurat,” the Iraq veteran in “White Fire,” Charles in the “Professor of Atheism” stories, and so on. The reason I am disconcerted is that I never set out to write about this character, and only find out that I have after the fact…. I don’t really know for sure, but I think that my fixation on this character has something to do with a desire to understand the quality of my own moral efforts — which, like most people’s — are never quite as pure or effective as they ought to be. In a way, all of these stories are about the role of the ideal in life, and they argue against absolutist moral idealism in favor of ordinary decency. I am, myself, something of an idealist, but for me the ideal is not a state that can or should be attained; rather, ideals are useful only because they help us understand the nature of our actions. It is important to bear in mind, for example, the ideal that one ought to keep one’s promises. But if one were actually to try to fulfill this ideal absolutely on every occasion, the results would be absurd and possibly barbarous. The ideal matters because it alerts us to the seriousness of our decision whenever we are confronted with the possibility, in this example, of not keeping a promise. I also think moral absolutism is a danger because it can be used to comfort moral complacency. Think of how many times moral efforts are utterly condemned because they have either not been perfectly successful or the people undertaking them do not have wholly pure motives. Activists of all stripes are constantly condemned in this fashion, and such condemnation serves primarily to salve the guilty consciences of those who don’t even try to do the right thing. My characters do try, and while I want my readers to be alert to the fact of my characters’ failure, I also hope that my stories serve to redeem my characters’ thoroughly ordinary goodness of will. Another reason why these characters interest me is that I see their struggle as primarily against the implacability of fate, which is represented in its most extreme form by death. I have always thought it something of a miracle that human beings struggle to do the right thing in the face of inevitable death. I feel exactly the same way about love. Many of my stories are attempts to celebrate the miracle of love in the face of death — which is, of course, the ultimate negation of all our efforts.

Catherine: The “Professor of Atheism” series that runs through the book entertaining on so many levels. How did that character develop for you? Do you think he’ll reappear in future work or are you done with him?

Stephen: As my answer to your first question indicates, the sources of my writing are a mystery to me. Characters seem to pop into my mind entirely unbidden, and with histories, habits, foibles and desires that I seem to have played no role in creating. That said, as my previous answer also indicates, Charles does have many precedents in my writing. But he, in particular, arose out of a paradox in my character. I am, and always have been, a dedicated atheist. I was raised entirely without religion, and the whole notion of God simply doesn’t make sense to me. But that said, I have always been attracted by the clarity with which religious texts can present some of the most basic human struggles. At the end of the Book of Job, for example, God, after having tortured this virtuous human being for not other reason than to make a point to His “adversary,” tells Job, in effect, “I’m the meanest motherfucker on the block, so you just shut up!”That ending has always seemed the perfect image of man’s relationship to that implacable fate, especially insofar as it implies that fate and justice are utterly unrelated. And I am also terrifically attracted by such extreme moral challenges as, “Love your enemy.” Like me, despite his disbelief, Charles finds himself attracted by and feels inadequate to one or another religious principle in each of these stories. The stories follow him through a period during which the principle seems quite wonderful, but they always end by showing the often tragic absurdity of the principle and the ultimate moral superiority of Charles’s groping, ad hoc decency… or at least I hope they do! Will I write any more “Professor of Atheism” stories? I have no plans for any right now — but who knows? Maybe Charles will pop unbidden in my head someday, and I won’t have any choice but to see what happens to him!

Catherine: What kind of non-literature things influence your writing the most?

Stephen: Having children and being a teacher in the New York City school system have been the two things that have most profoundly affected every aspect of my life, and for similar reasons. Both of these experiences opened up my heart to the suffering of other people. Before I had children, I had only a tepid, abstract sense of the horrors I saw everyday on the front page of the newspaper. But once I became a father, all those dead and suffering people came to represent possibilities for my own children, and reading those newspaper stories about them would fill me with such fear and pain. When I worked in the schools, I became acutely aware that good and talented children were constantly being ground up by the lives into which they had been born, and that, as hard as I might work, I could do little or nothing to help them. Many of the themes I have outlined above have obvious connections to these experiences. But I think the main way they have contributed to my writing is that though feeling more deeply about the world, I have also come to feel much more richly and completely alive. I think that literature is ultimately about helping readers become more deeply engaged in their owns lives, and I can only hope that whatever degree of such engagement I have been able to attain has helped me write better books.

Catherine: Do you have a new project underway?

Stephen: I am constantly working on new stories and poems, but am also working on a novel than has been haunting me for many years. Can’t wait to finally exorcise it!!! I also have an idea for a nonfiction book that I am tinkering with, although I don’t expect to get serious about it soon.

Catherine: I know you’ve had a tremendously busy year, but who are some of your favorite contemporary writers? (Bonus points if they’re with an independent press or have fallen through the cracks of the mainstream coverage.)

Stephen: Right now I am reading novels by Bruce Bauman, Terese Svoboda and Karen Russell, all of which I think are terrific. Bruce’s novel, AND THE WORD WAS, is published by Other Press, and Terese’s PIRATE TALK OR MERMALADE is published by Dzanc Books, so I guess I get extra points for those. Karen’s novel, SWAMPLANDIA! is forthcoming from Knopf, so no points, I guess… though that is not to say that mainstream presses don’t sometimes publish terrific books!

Tags: stephen o'connor

Oh gosh Catherine, I love this interview. You’re right, I’d never heard of O’Connor before, but now I’m going to have to order Here Comes Another Lesson. It’s always nice to see a writer profiled who’s undervalued or at least undermentioned around here.

“Ziggarut” is a beautiful little story. Good interview. I think browsed his collection on a table several months ago but now I will give it a more dedicated shot.

O’Connor is swell. I taught his story “Bestiary”–from the new book–to my undergrad fiction workshop just a couple of weeks ago. They’d never seen anything like it before. It was a lot of fun.

I had the honor of introducing Stephen O’Connor at the Gigantic + Open City reading last month in New York. I’ll say it again, because it deserves repeating, and is, in my mind, true:

Stephen O’Connor wrote the best story that was published in The New Yorker last year. I say this as someone who read at least 75% of the stories that were published and between 30-50% of the stories that were not published.

And his was the best.

It was the most moving, wildly surprising, and irremovable from my brain. “Ziggurat” was one of those rare things that you read and suddenly become full of feeling and associations. This is where I am, this is what I am thinking and feeling, this is what matters to me right now and in the foreseeable future. And then you go and want to tell everyone you know about this story and why it was so good.

Huh, that’s funny, the first issue of the New Yorker I ever decided to read was the issue with “Ziggurat” in it. I remember it being the only thing worth reading in the entire issue. Stephen O’Conner, you’re solid in my book.

Huh, that’s funny, the first issue of the New Yorker I ever decided to read was the issue with “Ziggurat” in it. I remember it being the only thing worth reading in the entire issue. Stephen O’Conner, you’re solid in my book.

[…] interviews Stephen O’Connor about his fine story collection, Here Comes Another Lesson. (A few thoughts […]