Author Spotlight

Interview with Bradford Morrow

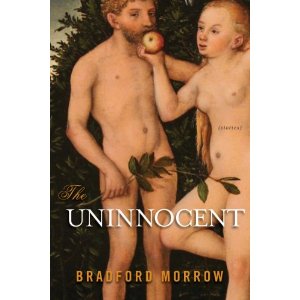

As both author and editor, Bradford Morrow, has been a major figure on the American literary scene for more than three decades. To date, he has published six novels (including The Almanac Branch, Trinity Fields and, most recently, The Diviner’s Tale), a novella (Fall of Birds), five collections of poetry, two illustrated books (including A Bestiary, a collaboration with Eric Fischl, Kiki Smith, Richard Tuttle, and fifteen other contemporary artists) and has edited nine collections of poetry and prose. Morrow is also the founding editor of the literary magazine, Conjunctions, which will publish its fifty-eighth issue this spring. His first collection of short fiction, The Uninnocent, has just been published by Pegasus Books. —Stephen O’Connor

As both author and editor, Bradford Morrow, has been a major figure on the American literary scene for more than three decades. To date, he has published six novels (including The Almanac Branch, Trinity Fields and, most recently, The Diviner’s Tale), a novella (Fall of Birds), five collections of poetry, two illustrated books (including A Bestiary, a collaboration with Eric Fischl, Kiki Smith, Richard Tuttle, and fifteen other contemporary artists) and has edited nine collections of poetry and prose. Morrow is also the founding editor of the literary magazine, Conjunctions, which will publish its fifty-eighth issue this spring. His first collection of short fiction, The Uninnocent, has just been published by Pegasus Books. —Stephen O’Connor

O’Connor: You call your book The Uninnocent. I am very interested in the idea of “un-innocence.” How do you distinguish it from guilt (not in the sense of the emotion, but of being responsible for a wrong act)?

Morrow: The way I think about it, if innocence is a state of grace, an absence of inner darkness, uninnocence is its antithesis: a state of perpetual shadow, one in which serenity and goodness are distant dreams, if that. While the darkness of the uninnocent isn’t always calculating—thepeople in these stories are not all born wicked—through the agency of some flaw or naïveté they simply break bad. Even before they’re guilty of anything, many of them never seem to be fated for an innocent life. The narrator of the opening story, “The Hoarder,” openly admits of his childhood self, “I was a weird little bastard.” He wasn’t yet a perpetrator of any misdeed, but innocence didn’t seem even to him to be a defining part of his character. One could fairly ask why coin the word “uninnocent” when the language is so replete with terms for the reprehensible, the blameworthy, the delinquent, the wicked. But while many of the people in my stories behave in ways that society appropriately considers wrong, or even depraved, my approach to writing about these individuals was from the inside out. It was important to me to locate a deeper grace or humanity within them and use that as an empathic starting place—a tentative innocence they themselves often do not recognize—and weave their failings around that fragile locus. Another aspect of uninnocence in the book is that so many are never caught or convicted of anything, and when they are restrained by authorities, they’re often convinced the system is working against them, don’t understand why the system has targeted them. John, the narrator of “All the Things That are Wrong with Me,” feels perfectly justified in doing the disastrous things he’s done and can’t understand why he’s been separated from normal society, forced to reside in a kind of Cuckoo’s Nest asylum with others who, unlike himself, are truly mad. And I more or less see where he’s coming from, though I disapprove of his basic vigilantism when he exacts eye-for-an-eye, tooth-for-a-tooth punishment on a kid who’s behaved sadistically toward his dog.

O’Connor: Many of your characters are decidedly “uninnocent,” and, in fact, commit acts that many people would describe as “evil.” And several of these same characters seem to be possessed by ideas or impulses that could themselves be called “evil.” The clearest examples of both manifestations of “evil” would seem to be the protagonists of three stories right at the center of the book, the title story, “Tsunami,” and “(Mis)laid.” I am wondering what you think of the concept of “evil.” Do you see it as designating anything that actually exists in the world?

Morrow: In other words, do I believe in the devil? I probably should, but I don’t. Humans manage to be quite bedeviled on their own and do unforgivably destructive things—i.e., “evil” things—to one another, without the influence of some satanic beast operating out of a fiery underworld. That said, the stories at the heart of the collection are clearly dark, although I myself find aspects of “Tsunami” and “(Mis)laid” comical, as well. I like your expression “possessed by ideas or impulses” as a way of describing how Angela, Lorraine, and the man who mislaid his mind function in a world that is somewhat alien or incomprehensible to them. Angela, who believes she is following suggestions given to her by her dead brother, suggestions that lead her to act reprehensibly, may be delusional but her ghost is more real to her than anyone actually alive. Lorraine murders from two equally viable (to her) perspectives: quiet rage and maternal compassion. “(Mis)laid” is a kind of drawing-room-cum-police-procedural comedy fueled by jealousy and a couple of snapped minds. As hurtful and even murderous as these protagonists’ actions are, though, I doubt I would be able to get any of them—were I able to sit and discuss matters, one on one—to admit to any feelings of guilt. None would associate the concept of evil with their activities.

Morrow: In other words, do I believe in the devil? I probably should, but I don’t. Humans manage to be quite bedeviled on their own and do unforgivably destructive things—i.e., “evil” things—to one another, without the influence of some satanic beast operating out of a fiery underworld. That said, the stories at the heart of the collection are clearly dark, although I myself find aspects of “Tsunami” and “(Mis)laid” comical, as well. I like your expression “possessed by ideas or impulses” as a way of describing how Angela, Lorraine, and the man who mislaid his mind function in a world that is somewhat alien or incomprehensible to them. Angela, who believes she is following suggestions given to her by her dead brother, suggestions that lead her to act reprehensibly, may be delusional but her ghost is more real to her than anyone actually alive. Lorraine murders from two equally viable (to her) perspectives: quiet rage and maternal compassion. “(Mis)laid” is a kind of drawing-room-cum-police-procedural comedy fueled by jealousy and a couple of snapped minds. As hurtful and even murderous as these protagonists’ actions are, though, I doubt I would be able to get any of them—were I able to sit and discuss matters, one on one—to admit to any feelings of guilt. None would associate the concept of evil with their activities.

O’Connor: As the previous question indicates, many of your characters are possessed by powerful ideas that inspire not only brutality, but oddly charming and very funny acts. My favorite example of the latter is the protagonist of “Ellie’s Idea,” whose conviction that she should apologize to everyone she has ever wronged backfires in ways that she never quite recognizes. Another result of so many of your characters being blinded by powerful ideas is that several of them make decidedly unreliable narrators—the most striking being the narrator of the aptly named “The Enigma of Grover’s Mill.” Could you talk a bit about your use of the unreliable narrator, and, in particular, about how you manage to get your narrators to convey things to readers that they themselves don’t notice or understand.

Morrow: Well, as Shakespeare wrote, you can smile and smile and be a villain. Some of the nastiest people I’ve met have also been among the most charming. In the same way that it takes a lot of truth to fabricate a believable lie, a good sense of humor and alluring charm are invaluable to the success of, say, a serial killer. Each of us contains multitudes, as the saying goes, and for me the psychological interplay betweeniniquity and more socially negotiable behavior is fascinating. Don’t forget that Reinhard Heydrich, the Butcher of Prague and one of Hitler’s favorite sons, was a good family man, a devoted husband, a lover of classical music. Any character who is all bad is a thin gruel of a character. Ellie, who is no Heydrich by any stretch, is an interesting character to me. I’ve encountered an Ellie or two in my life and probably you have, too. She’s a particularly good example of what I mean by uninnocent. To her mind, her mission is to wipe her slate clean through the simple act of apology. On the surface this seems like a pretty good idea. But her naïveté proves to be unintentionally (for the most part) destructive, and the very innocence that prompts her to think her confessions will make a positive difference in her life begins oddly to corrupt her. As her world ostensibly improves—or so she sees it—and her small sins are self-absolved, the tangled and fragile worlds of everyone in her acquaintance begin to collide and implode. Motivated by goodness she morphs into a figure of, if not evil, certainly catastrophe. That old saying “The road to hell is paved with good intentions” might have made a good epigraph for “Ellie’s Idea.” Regarding unreliable narrators, my sense is that one of the hallmarks of unreliable narratives is that the narrator does not feel that he or she is unreliable in the least. Wyatt’s growing obsession with and hatred for his grandmother’s houseguest Franklin does begin to blind him, as you say, so that by the end of the story it is utterly unclear whether or not Franklin is a Martian (I realize this comment will sound crazy to anyone who hasn’t read the story yet, but in context it does seem possible that Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds, set in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, might have created a kind of wormhole for a true alien invasion, at least in one young man’s mind). And though the reader may consider Wyatt unreliable, Wyatt would strongly disagree. I’m not sure there’s a particular writerly trick that is used to allow narrators to convey things they don’t understand, though I must admit that in fact most of my characters are blind to their shortcomings (one quite literally) and cast the blame elsewhere. But I think that’s a fundamental way many of us negotiate our paths through life—although, granted, not generally to the degree those who populate The Uninnocent do.

O’Connor: There is a great deal of anger and violence within the families of your stories—between brothers, a brother and a sister, between husbands and wives. There are also several stories in which a brother and a sister are so close that their relationship seems to have negative effects on both their lives. I wonder if you care to talk about the inspiration for these families.

Morrow: Few relationships in life are more fraught than family. We choose our friends, but our families are the result of genetic fate. So yes, I love exploring the deep dynamics, not always pretty, of kin. I find it interesting that siblings, those with whom we grow up and share so many early, formative experiences, who intimately know our flaws and frailties, can either be true soulmates or else use that knowledge to undermine us, even hurt us the most. Families are stew pots, and the stew can be either healthy or poisonous. As for the inspiration behind some of my brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, I can’t really point to my own small clan, although we had and have our own issues, like any other family. Over the years I’ve observed the families of friends or loved ones, and while none are necessarily as psychotic as those I draw in my stories, the possibilities are there. Scratch just beneath the surface of many a holiday family photograph and you will find the attic monster, the cellar psycho, sitting at the table ready to enjoy turkey and trimmings along with everybody else. Usually he’s the one with the biggest grin. Sometimes he’s the carver.

O’Connor: Things seem to have powerful connections to people in these stories. Two of your characters steal things from important people in their lives. The narrator of “The Hoarder” collects things, and the narrator of “All the Things that Are Wrong with Me” collects animals. And several of your characters are amateur or professional archeologists—most notably the brother in “Gardener of Heart”—who reconstruct lives from the things left behind. Could you talk about how our relationship with the things we possess came to play such a prominent role in your imagination?

Morrow: You know the word numen? A magical spirit or power that inhabits an object? A numen can reside in a bush, a stone, a house. It animates any otherwise inanimate object. My fictive worlds are decidedly numinous in this way, and the things my characters collect sometimes come to define who they truly are. As a writer, when I’m working my way into characters’ heads and hearts, one of the first things I like to figure out early in the process is how they view the physical world, what their relationship is with the world they find themselves in. The young guy who narrates “The Hoarder” is a bit of a loner, his mother having left the family, his father itinerant and going from job to job, his older brother never missing an opportunity to cut him down to size. He collects little things at first. Seashells, birds’ nests. But as his hormones kick in along with a deepening resentment toward his brother, his ambitions grow and skew, and his earlier rather harmless pastime turns sinister. Inanimate objects like seashells and pottery shards, though compelling and even enchanting to him when he was younger, don’t cut it anymore. Whatever numen may have resided in any of those objects wouldn’t prove to be quite as interesting as the living, breathing spirit that was his brother’s girlfriend, Penny. Once he graduates from one kind of hoarding to another, his passion for collecting, perhaps obsessive-compulsive from the get-go, moves decidedly into the realm of uninnocence. Somewhat similarly, John, the narrator of “All the Things that Are Wrong with Me,” doesn’t function well in human society and so he prefers the company of animals, assembles his “menagerie” of animal friends which, though relatively harmless at first, will get way out of hand and bring him down. With regard to archaeology, I think that in another life I’d have loved to be either an anthropologist or an archaeologist, puzzling out civilizations through their languages, their myths, their artifacts. The archaeologist in “Gardener of Heart” has spent a lifetime sifting through the ruins of ancient dwellings, cobbling together possible narratives of the people who lived there long ago, that I believe he may have slipped into a city of the dead himself without at first noticing any difference. I’m particularly fond of that story, by the way. Like “The Enigma of Grover’s Mill” and possibly the title story, it combines elements of the gothic with those of fantasy.

O’Connor: As Hemingway did in In Our Time, you seem to have arranged your stories in such a way that, although none of your characters reappear, the characters in each successive story seem, to some degree, to be living out the consequences of the actions of the characters in the stories that have preceded them. Sometimes actions are repeated in juxtaposed stories—scarves are stolen, for example, in both “Ellie’s Idea” and “The Road to Nadeja.” And, of course, there are repeated situations: all those angry families and those over-close brothers and sisters. But, when read in order, the stories seem to follow what we might term an “inverted narrative arc,” descending toward catastrophe from the beginning to the middle of the book, and then rising thereafter toward some sort of rough redemption, which is most fully achieved in the collection’s very moving final story, “Lush.” Could you talk a bit about how you arranged your stories? Did you actually conceive of them as forming a “secret” novel? Did your desire to unify the collection have any effect on how you wrote the individual stories?

Morrow: I did agonize over the order of the collection and did my best to arrange them so that a kind of symphonic narrative, a series of movements, would be in play as one read through the book. While I didn’t intend for The Uninnocent to be a secret novel, I knew that “Lush” absolutely had to be the last story with its final note of tentative redemption and that “The Hoarder” and “Gardener of Heart” offered readers the best entree into these thematically connected narratives. You’re right about certain images, gestures, themes, even objects echoing here and there in the book. The decision (or intuition, more like it) to do this was as much a musical one as anything else, a patterning that would help gather the individual pieces into a whole.

Although most of the stories were written separately over the past ten years, they definitely share a gothic sensibility, and that undoubtedly lends the collection a coherence as well. At one point I toyed around with the idea of titling the book All the Things that Are Wrong with Me, because every individual story includes a confession of or exploration into our deepest defects, and frailties, the things that are wrong with us. Despite their flaws, though, I have a great fondness for even my most ruined and bleakest of characters. At times I found myself horrified by what they were doing and saying while I was writing, and I wanted to step in and tell them, No, you can’t possibly do this or think that. But each of these souls was on a set spiritual course. I could no more deny them their sins than try to add two and two up to something other than four. In other words, there were inevitabilities that began to surface in the actions and behaviors of the protagonists in these stories, inevitabilities that I myself couldn’t stop or even impede without being unfaithful to my characters. I tried to stay true to them at each and every turn, even when that turn took them on a descent into sorry, even tragic places.

Tags: bradford morrow, stephen o'connor

phlpn.es/829r8s

phlpn.es/829r8s

linkhide.com.ar/47632

phlpn.es/829r8s

phlpn.es/829r8s

ai.vc/uj

50.gd/2g

50.gd/2g

[…] O’Connor’s interview with Bradford at HTML Giant GA_googleAddAttr("AdOpt", "1"); GA_googleAddAttr("Origin", "other"); […]

liil.cc/chX

[…] At HTML Giant, Stephen O’Connor interviews author and Conjunctions editor Bradford Morrow. […]

Great Interview! Thanks