Author Spotlight

It was our blood and guts: an interview with Patrick deWitt

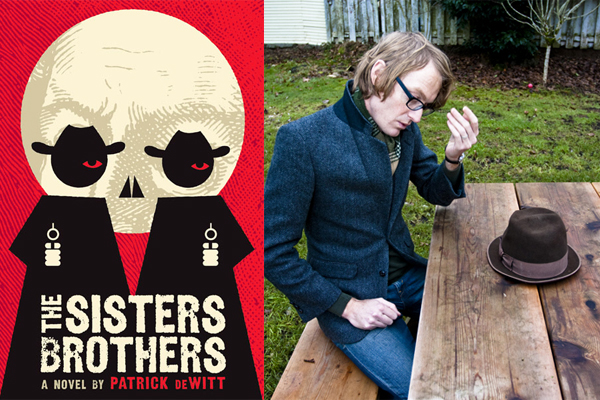

Last year, many of us read Patrick deWitt’s excellent Western The Sisters Brothers. The novel (which I reviewed here) concerns two brothers, Eli and Charlie, who hurt and kill men for a living. A great work in a little-appreciated genre, the book went on to win a Governor’s General Literary Award and a Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and was short-listed for the Man Booker Prize. It is newly released in paperback (though I’ll admit I like the hardback’s cover better, and for my part, I read it on the Kindle). He is also, though the interview doesn’t touch on this, the screenwriter behind the recent film Terri. Mr. deWitt was kind enough to spend a little time with some questions I sent him. I don’t know if I touched his soul or anything, but his answers were good, and his book is very much worth your time.

In an interview for the Man Booker Prize, you said: “It would be harder for me to write those same scenes without the twist. In real life, violence is graceless, pathetic, weird, or simply funny. But it’s almost never righteous or noble, and I tried to avoid writing about it that way.” I think a lot about violence, but I’ve never really experienced it myself. The idea that it’s not noble or righteous isn’t too surprising, but “pathetic” and “weird” are two adjectives I’ve encountered less often, I think, and I like them. Reading this made me curious about your experience with violence, and what leads you to see it in the way that you do.

I was never a violent person. It was never something I had any stomach or aptitude or reverence for. I went to a lot of punk etc. shows starting at the age of 12. This was in the San Fernando Valley in the late 80s, and anyone going to these shows certainly saw a lot of violence, though it wasn’t mandatory to take part, and I found it easy enough to skirt. Later on my friends and I got into drinking and drugs, and this was a blood-and-guts period of time, but it was our blood-and-guts. It was ugly but we weren’t, you know, marauders. Later still, working at a bar, fights were common, and these usually matched the description above (pathetic, weird). This was probably where I adopted that attitude toward violence, actually. We’d just stand there and watch. I remember these two meaty white guys with shaved heads going at it on the floor. They’d ripped each other’s shirts off, and a customer looked at me and said, “It’s like babies fucking.” Physical confrontation is just an awkward social interaction taken to the extreme, it seems to me.

When you see something like the “babies fucking,” do you have that thing where you find yourself thinking about it as potential future material? I’ve always felt weird about that instinct.

When I was writing Ablutions, I actually hunted for specific incidents to use. If something interesting happened at work, I’d write it down to recall it later. But for the most part I don’t lift factual happenings in this way. It’s more like the things I’ve witnessed or experienced inform my attitude, which informs the overall work.

You’ve said that The Sisters Brothers represents a return to story for you, coinciding with a similar return in your reading. This ambivalence re: story seems common among a lot of my favorite writers, and I guess I wonder what causes it. How did you drift away from story in the first place?

I think it’s the natural path for any curious artistic person, like a painter discovering the abstract, and the line is suddenly exploded. It’s exciting when you realize there aren’t any hard and fast rules; but then, too, constraints can push you to places you might not have arrived at if you’d been unimpeded. If the weather’s poor, I’ll say to my son: You can do anything you want, but you have to stay inside the house. Writing The Sisters Brothers was a bit like that.

Where did the constraints of plot and genre push you in this case?

Anything that didn’t propel the story was scrutinized, and I lost a lot of what I felt was good work because it didn’t assist the whole. I guess this is just how regular (?) people write, but it was new to me, and I found it a severe discipline.

Here’s a quote from a much older interview with our own Matthew Simmons, this time at Hobart: “I mean, there was no reader, so I couldn’t concern myself with upsetting his or her expectations.” I found your saying this really surprising; it seems like even if you have to use yourself as a proxy for “the reader,” it would be difficult to write without that end user in mind. And yet, it’s true: there is no reader. How do you work with that absence?

I was referring to the period when I was working on my first novel, and hadn’t really published anything. I was being literal — no one was waiting for that book. After it was published I picked up a few readers, and I can remember moments during the writing of TSB where I wondered what they would make of it. But for the most part I don’t consider the reader until the work’s done. This isn’t an intentional exclusion; they just don’t come to mind.

You’ve said that originally The Sisters Brothers had more supernatural elements — remnants of which can still be seen, especially in the interludes. I’m curious what about the novel seemed to call out for these elements, and what ultimately led you to (mostly) excise them. It seems as though in some ways the gold rush mentality makes actual magic redundant, maybe.

I thought it was important for there to be oppositional forces that Eli was afraid of. This goes back to my not wanting him to resemble the classical hero model too closely — the near mute man in black who kicks the devil in the dick before breakfast.

In terms of my cutting so much of that stuff: My wife read an early draft, and she thought the supernatural elements muddied the root story. I hated to lose any of it, but she was right, and I went about chucking the bulk.

Do you have any particular strategies you use when you’re revising a novel?

It’s a by-the-numbers sculptural process. The first draft is the big slab, and I hack and hack at it. Then it becomes more particular — paragraphs and sentences are the focus, rather than entire sections. When I get to the point where I’m swapping periods for semi-colons, back and forth, over and over, then I know I’ve gone as far as I can on my own, and I search out input.

I’m a huge fan of comic pairs. Eli and Charlie are a wonderful example of the type. What are your favorite comic pairs in fiction, film, or elsewhere?

I like Sheldon Kornpett, D.D.S., and Vincent J. Ricardo from The In-Laws (1979). George and Martha from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? are pretty funny. Derek and Clive. I can’t think of any literary pairs. Tricky question for some reason.

Was there a particular scene where you felt that the dynamic between the brothers — their differences, their wonderful mixture of combativeness and tenderness — snap into place?

After I finished writing the scene where Charlie tells Eli how he got his freckles, which ties into the story of how Charlie murdered their father, this was the moment where I felt I finally understood them, both as individuals and as a pair.

I want to ask you where the name “Hermann Kermit Warm” came from, but I have a feeling you’ll say “I made it up.” But I have to ask! It’s such a good name.

I didn’t make it up. I stole it. I was watching Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and a Hermann Warm was credited as the art director. He’s got a Wikipedia page and everything. I added the Kermit, because I like the musicality of the added syllables, but really, I just lifted it.

What was the weirdest thing you read about the gold rush culture in your (limited, you’ve said) research?

Maybe not the weirdest, but the thing that was most interesting to me was how people reacted to what was happening in California. Thousands and thousands of men and women left their homes and families to hurry after a dream they didn’t know they had. Pretty foolhardy on the one hand, but it also shows a faith and optimism that I find admirable.

Tags: Ablutions, Patrick deWitt, Terri, the sisters brothers

Thanks for this. That photo is a classic, too much.

Great interview. Great book.

[…] Q&A with novelist Patrick deWitt (The Sisters Brothers). Here. […]

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/author-spotlight/it-was-our-blood-and-guts-an-interview-with-patrick-dewitt […]