PQRS

PQRS

by Patrick Durgin

Kenning Editions, Feb 2013

80 pages / $12.95 Buy from SPD or Kenning Editions

If poets theater is first and foremost “about the scene of its production,” as Kevin Killian and David Brazil claim in their intro to the new Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater, what is contemporary poet’s theatre “about?” Patrick Durgin’s PQRS, the audience becomes the company charged with producing the writer’s script. Casting the steadfastly oblique dialogue tasks the imagination, but the ample, winding stage directions provide a topology. Reading the text could be compared to hitting a salad bar with the smartest people you know–a justifiable decision for an evening, though filled with silent chewing and self-effacing questions. In this way, PQRS proves both informative and tiresome, upbuilding and desolate, all at once. The title names both the four players of the script, and a government incentive program which allows physicians to recoup part of their Medicaid payments by the timely submission of quality reports to a central agency. As a publishing house, Kenning has been hoarding infectious manuscripts; Laura Elrick’s Propagation is a parasitic worm that undermines the sense of rhythmic continuity in the ear and eye, and the germ of critique transmitted in PQRS inflames doubt around the positivist psychological organism most humanisms revere. Durgin’s players grope through the dissolution of soliloquy and turn essay in on itself through a fallacious argument for pornography. Much in the way that ancient drama was a mirror held to the polis, poet’s theater can be an instrument of self-reflection for a coterie of writers and artists to have a view onto their current historical assemblage. If this is the only goal of PQRS, which would be enough to ask, then Durgin provides us with a full serving of our current end-of-days squabbling, financial hi-jinx, and artistic quietude. The book is adorned with photos of meat, on the front, the cut is obscured into an eerily lifeless landscape, and on the back, fluttering, unfocused bacon. The book’s motion mimics the replication of DNA, or the motion of Hegel’s dialectic, a strange but life-sustaining pattern for a play that abjures dramatic structure. Act One and Two oppose each other, with S overcoming Q &R’s sidebar, and the metaphysical interlude between Acts Two and Three becomes the fulcrum–and the transformational moment–around which opposed modes of communication crumble, leaving again a ground. That interlude of intimacy between writer and reader comes free of staging and soothes the screeching moments when the players of the script make attempts at dialogue.

At the opening of Act One, Scene One, S, who shares a heritage but not temperament with her co-stars, creates a snug, rectangular enclosure by rolling out neutral linens onto the stage. In the striking book of portraits Daughter, images from childhood inhabit a similarly inscribed space. Part of S‘s role in the play is to speak of, about and on behalf of essay as a genre [as opposed to say, metaphysics]. “It should be possible to enjoy a commanding view of [X]… but numerous renditions, beheadings, dismemberments, and coats of paint have compromised the historical continuity of this perspective, or rather problematized its plausibility” is a weak skepticism, and points the reader to the probability that some of what is happening is lost on us. Not an unfamiliar feeling in the land of instantaneousness. It seems one of the premises of the Durgin’s play is the inevitability of one’s keeping of a ‘commanding’ view of the new regimes and regimens of production, commanding in the sense that, like the LCD screen, a view has a logic and reproducibility which circumscribes the user’s actionable possibilities. One only does away with such a view at the behest of society, and the ‘poeté maudit’ tradition may be informing the implosion of form that the user of this book will sense in the periphery.

I choose the word user because one detectable context for the play is the coterie of users, and if you are reading this, you are likely instantiated more in user-hood than in the population of human bodies. Daughter is heavily indebted to this mode of thinking as well, as the photographs of sticker-book collages are cropped and wrought in yellowed tones that mimic Instagram’s manufactured nostalgia. The flip-side of these photographs are snapshots of pre-literate scribbling, evidence of the nascent self-reflective impulse “to write.” Presumably all credit goes to his infant daughter there. The timeline of the composition of PQRS stretches from the late nineties dotcom bubble to the jarring present. The book is deliberately assembled, though perhaps frantically and mindlessly written at times. S opens Scene Two by opening a laptop which gives a tinny version of the enveloping music from the previous scene, and an email appears as the book’s only moment of soliloquy, when it is disclosed how parts of the production were composed. The concepts underlying the production process seem to be ones that the regime of the user has ushered in: wiki-composition, textual mashups, transparency, tumblr. But the text here doesn’t obtain mastery of execution, but rather a kind of energizing interference by its pursuit of those ephemeral objects.

Durgin, who is the founder of Kenning Editions, is like the franchise owner and the star player at once, and to a larger audience this could seem a conflict of interest, the suspicion doesn’t amount to much, in fact, it makes PQRS a more emboldened, decisive book. One might even deflect the accusation and point to a scene in Act Two which is a ‘wiki’ of hypothetical performance art pieces, from Shanghai to Vienna to the Twin Cities, all submitted by other assistant professors. This part of the book may intrigues by its method, and yet is the most resistant to the page, and needs the dressing of research to be supported by the average imagination. To continue the salad bar analogy, this scene is the one large bowl in the middle holding the standard house mix: romaine, iceberg, bleeding cherry tomato, Sol Lewitt, minced cucumber, more romaine, and art-house cinema. It’s the bowl that everybody reaches for in order to get good plate coverage, but whose only real function is to keep digestion “regular.” Other scenes do provide the intelligent critical moments and savory metaphysical propositions. The additional scenes are not meant for as a main course; they are toppings which provide a technique of characterizing each eater/actor/professor, only after they have padded the plate with the proverbial ‘meat’ of the salad bar enclosure. Finish with croutons, watercress, and foreign travels. The blurbs call the book “a monumental failure” and “a world whose very conceptual difficulty supplies a context for new models of dramatic form and provides a vehicle for the kinds of thinking and representing that happen when various avant-garde ideologies collide with the twin crises of postmodern irony and capitalist recuperation,” but I maintain that it is a salad bar, probably one of anti-capitalist practices for the user generation. In being this, it utterly succeeds, providing a commanding view onto the landscape of discursive and technological obstacles resistance will confront during the decades we face presently.

At the end of the first act, S responds to Q’s recited mashup of Rimbaud and a news article on US dollar hegemony by counterposing the didactic lyric poem and the essay, a binary which epistemologically eviscerates her. Unironically, Durgin allows her to toe the line between mystic idealism and crude materialism, the shitty first marriage of the intensive and the extensive [the psychological and the physical]. The user of the text confronts an interrupting realization: when reading “to stay informed” and “for pleasure” are two sides of the same coin, what other drives can a reading practice attempt to satisfy? If one cannot choose misery, attempting to recognize the open failure of the essay and the soliloquy, to which all user-interaction may boil down, becomes a kind of spiritual exercise. For all the genre-centered hand-wringing that the press is offering, PQRS is still a book, a heavily regulated and easily apprehended object, though if the writings inside are dense enough resist intelligibility. But the consuming project of the Kenning imprint is starting to come into sight with this release, alongside Daughter and the anthology of poet’s theatre. The audience for PQRS is somewhat implicated in the failure to sustain a responsive, self-modulating theater to replace the death-mongering meritocracy of the civilization, and this might be dissatisfying for some. But the recent works of Kenning, taken together, are starting to resemble the opening lines of a broader spiritual gesture, reminiscent of the forging of cadres done by Stein, Duncan, Olson, and the New York School. Durgin just happens to be the curator now, versifying a terrible renewed fortune for the sea of users-to-come.

***

C.J. Morello is a poet with a B.A. in Philosophy from UChicago and an M.A. in Writing from UC–Davis. His writing is forthcoming in Gigantic, and tweets come forth @siegethethird

Can It!

Can It! Imperial Nostalgias

Imperial Nostalgias Brando, My Solitude

Brando, My Solitude A Far-Shining Crystal

A Far-Shining Crystal

Strange Intruders

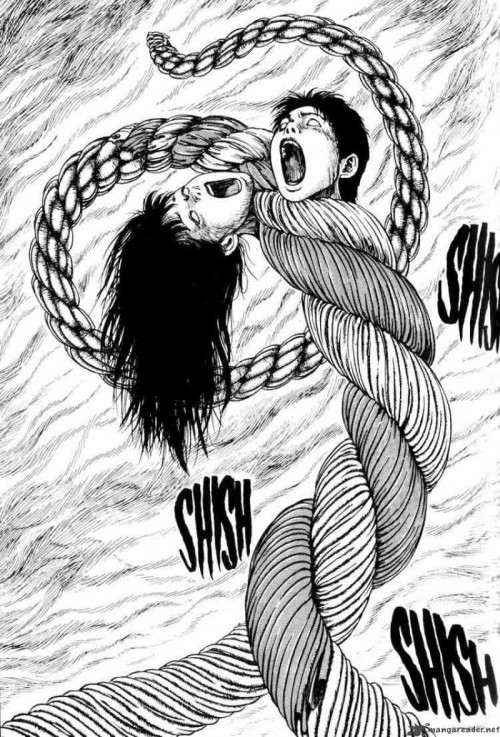

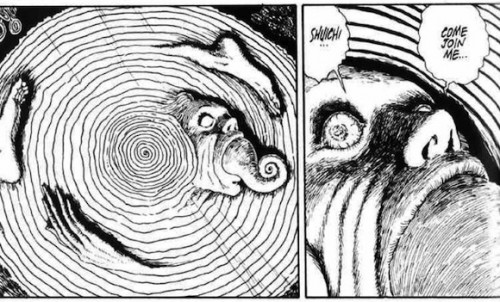

Strange Intruders Uzumaki

Uzumaki The new hardcover edition from VIZ Media is a welcome upgrade over the paperback volumes. In this larger format book, Junji’s Ito’s starkly beautiful black and white artwork looks better than ever. Although the film adaptation of Uzumaki captured the general strangeness of the work, this is a story that’s best told in black and white. The images are horrific but naturalistic, and there’s a subtlety to the characters in both the art and dialogue that makes them more sympathetic and relatable than the characters in most of the manga I’ve read. Arguably Junji Ito’s crowning achievement, and without a single dull page in the mix, it’s 600+ pages of terror and beauty. My wife and I each keep a shelf of books we’d take with us in the event of a zombie apocalypse. These are the books that mean the most to us, the ones we couldn’t bear to part with. This edition of Uzumaki in hardcover instantly earned a place on my zombie apocalypse shelf.

The new hardcover edition from VIZ Media is a welcome upgrade over the paperback volumes. In this larger format book, Junji’s Ito’s starkly beautiful black and white artwork looks better than ever. Although the film adaptation of Uzumaki captured the general strangeness of the work, this is a story that’s best told in black and white. The images are horrific but naturalistic, and there’s a subtlety to the characters in both the art and dialogue that makes them more sympathetic and relatable than the characters in most of the manga I’ve read. Arguably Junji Ito’s crowning achievement, and without a single dull page in the mix, it’s 600+ pages of terror and beauty. My wife and I each keep a shelf of books we’d take with us in the event of a zombie apocalypse. These are the books that mean the most to us, the ones we couldn’t bear to part with. This edition of Uzumaki in hardcover instantly earned a place on my zombie apocalypse shelf.

Damnation by Janice Lee

Damnation by Janice Lee Love Dog by Masha Tupitsyn

Love Dog by Masha Tupitsyn BTW: A Novel by Jarett Kobek

BTW: A Novel by Jarett Kobek Mandy, Charlie & Mary-Jane: A Novel by Stewart Home

Mandy, Charlie & Mary-Jane: A Novel by Stewart Home Antiepithalamia: & Other Poems of Regret & Resentment by John Tottenham

Antiepithalamia: & Other Poems of Regret & Resentment by John Tottenham Beneath the Liquid Skin

Beneath the Liquid Skin  PQRS

PQRS