Behind the Scenes

Chicks Dig Pink, Frilly Things and (Domestic) Porn

When you write a book with the title It’s A Man’s World, with the tagline “but it takes a woman to run it,” you have to have some sense that your book is going to be marketed in a certain way. I haven’t read the book in question, but the title certainly gives an impression. Maybe it’s just me but when I see that title, I think “chick lit.” I also enjoy “chick lit,” so that label is not a bad thing. That book’s author, Polly Courtney, recently had a very public reaction to how her book was being marketed as “chick-lit,” announcing she was leaving her publisher, Harper Collins, so her writing wouldn’t be pigeonholed. As writers, we often have to worry about whether or not our work will be pigeonholed based on some aspect of our identity. No one wants their creativity limited or misrepresented; pushing back against rigid, often unfair categories is a natural response for a creative person.

In her explanation for why she was leaving her publisher, Courtney distinguishes between women’s fiction, which she writes, and “chick lit,” which she very much does not. I gather that women’s fiction is serious while “chick lit” is not. She writes, “Don’t get me wrong; chick-lit is a worthy sub-genre and there is absolutely a place for it on the shelves. Some publishers, mine included, are very successful at marketing this genre to women. The problem comes when non-chick lit content is shoe-horned into a frilly “chick-lit” package. Everyone is then disappointed: the author, for seeing his or her work portrayed as such; the readers, for finding there is too much substance in the plot; and the passers-by, who might actually have enjoyed the contents but dismissed the book on the grounds of its frivolous cover.”

Depending on the content of the book in question, Courtney is correct in noting that disappointment is possible for everyone involved in the consumption of a book. At the same time, isn’t a cover is just a cover? Eventually, the writing speaks for itself and either readers will like the work or they won’t. Readers are fairly sophisticated these days, aren’t they? I would like to believe readers will, more often than not, have a good sense of what a book is or isn’t about no matter what is emblazoned across the cover. Unfortunately, such does not seem to be the case and certain books are burdened by covers that alienate certain audiences.

We do judge books by covers. That’s why books have covers instead of plain cover stock bearing only the book’s title and author. When we’re browsing in a bookstore, we need a reason to pick up a book and flip through its pages.

When we see books with pastel covers and shapely legs or perfume bottles or the female silhouette on the go, we are also given a certain impression. In a 2006 article about “chick lit,” for Print, Jami Attenberg wrote, “A cosmopolitan glass indicates a sexy edge and big mistakes in pursuit of happiness; a whimsical, cursive title alerts consumers that the narrator will eventually knock over a tray of glasses in a roomful of glaring partygoers. A high heel forecasts a neurotic, shopping-prone city dweller, while a bare foot promises a more personal, emotional tale (especially if the foot’s been intricately hennaed, thus tagging it as Indian-American chick lit—not to be confused with Asian-American, African-American, or Latina chick lit).” The covers of “chick lit,” and other women’s books are deliberately coded in certain ways and time and again we are shown that those codes can be extremely limiting and, at times, inaccurate. I don’t know that all the blame rests with publishers, though. We have to be responsible for the nature of our perceptions.

It is curious how publishers decide what should appear on the covers of books written by women. Few authors have control over their book cover. Most writers will get some say, but at the end of the day, the publisher makes the final decision about how a book is designed and marketed. More often than not, publishers assume women write books for women rather than for everyone and that men shouldn’t even be considered as a potential audience. That’s what’s certainly implied by the covers of many women’s books. We do know more women buy books than men and as such, publishers market books with that reality in mind. The way these books are marketed, though, positions most books written by women as lighter reading fare that doesn’t tackle the serious subjects men write about. Given most book covers, we ladies should probably just amuse ourselves with airy little novels about shopping and sex and perhaps, once in a while, the amusing trials of motherhood; we’d best leave the heavy book lifting to the menfolk.

Cathy Day is working on a great visual essay, “(Don’t) Judge A Book by Its Cover,” about the feminization of book covers. She started working on this project when she realized her women students were hesitant to write about certain subjects because they didn’t want a frilly pink cover slapped on their book. In her essay, Day shows how most women’s books use, “soft focus, photography and domestic objects,” drawing on the “domesticity porn” of women’s lifestyle magazines. It is startling to see how books from twenty or thirty years ago have drastically different covers today–covers that imply that every book a woman writes is frilly “chick lit.” The way the cover of My Antonia, for example, has been redesigned over the years, is particularly galling.

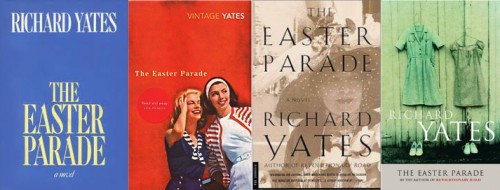

One of the more interesting parts of Day’s visual essay is when she shows how male writers are also subject to the feminization of their book covers, comparing Richard Yates’s The Easter Parade when it was first published and how the book looks today as if women need to be tricked into buying serious books by using the same design approach applied to “chick lit” and women’s fiction.

When I first read about Polly Courtney’s decision and her frustration with how her work is being marketed, I found her reaction strange. When a woman writer puts such effort into distancing herself from the stain and stigma of “chick lit,” I tend to think personal biases are clouding their judgment. Or, the decision was a well calculated move. If Courtney hadn’t made her announcement, I would have never heard of her book. I thought, “My publisher can put whatever they want on my book cover.” Then I remembered Day’s essay (you can find an excerpt of the project at She Writes). The issue is complicated. A book’s cover should reflect what the book is about. It’s unfair to try to force a woman’s book into a certain genre and set of codes simply because she is a writer with a vagina. It undermines us all.

What truly concerns me, though, is how much effort too many women writers (are forced to) put into explaining their work as “serious” and not “chick lit.” Women are still being placed in this awkward position where they never get a chance to talk about their writing because they have to worry about how they will be pigeonholed and misrepresented. That we feel the need to defend or explain our work is the problem, not that the “chick lit” genre exists or that our writing is unfairly pigeonholed when we tackle certain subjects.

This conversation about “chick lit,” versus other fiction genres is a recurring one. Earlier this year, Jennifer Weiner bristled when Jennifer Egan indirectly made some less than charitable comments about the genre. Last year, many women writers, and Jennifer Weiner and Jodi Picoult in particular, had strong reactions about the level of hype Jonathan Franzen received for Freedom in a melee that even got its own name–Franzenfreude. That conversation positioned literary fiction against the purportedly lighter “chick lit” fare. I understand why women writers feel defensive and a bit raw about the “chick lit” label and yet I often feel like we do ourselves more harm by obsessing over the term and whether or not it is applied to writing.

The term “chick lit” is inadequate but language, in general, is inadequate. There is a male equivalent, the equally unfortunately named “lad lit.” The genre doesn’t receive as much critical attention as “chick lit” but it exists despite persistent reports of its demise. “Lad lit” books are quite similar in tone to books labeled as “chick lit.” There is, however, far less outrage over the term “lad lit,” probably because men don’t have to fight to be taken seriously in the same ways women have to fight. When men write in this genre, the choice is generally deliberate, not forced upon them. Still, I wonder about the benefit of spending so much energy worrying about the term “chick lit” and what that term means and whether or not it is (mis)applied to our work. Does the label matter? That seems like the wrong conversation to be having.

Last week, an article in Entertainment Weekly began, “For some smart, young female novelists, having their books branded “chick lit” is the worst imaginable insult. ” Everything about this conversation is imbued with troubling rhetoric. That statement positions intelligence as the antithesis of “chick lit.” And is that really the worst insult that could be lobbied against a woman writer? To consider the label “chick lit” the worst imaginable insult is, at best, a failure of imagination and at worst, evidence of internalized sexism. That article goes on to note that there are women’s books that overcome the “chick lit” label. I’d love to see us get to a place where we don’t see such a label as an obstacle. So what if a book cover is pink or frilly or domestically pornographic? Why do these markers of femininity, accurate or not, have to be perceived negatively? Pink is my favorite color. There are several issues here–the way books are marketed and the way women writers are pigeonholed by gender instead of having their writing assed on its own merits are issues that deserve our attention. The far more serious problem is the sexism (or is it misogyny?) fueling this conversation, the sexism that makes women feel so defensive and that encourages people to dismiss or disrespect women’s books whether they are “chick lit” or women’s fiction or literary fiction. Until we recognize and address the sexism at work here, we’ll continue wearing ourselves out by dealing with symptoms rather than the disease.

Tags: chick lit, Harper Collins, Polly Courtney

It is definitely a little odd to complain about your writing being pigeonholed when the first words of your subtitle are “I write women’s fiction.”

Also, I hesitate to say this because I thinks ome of the issues you raise here are very vital, but in regards to this one author her own website…which I assume she has control over…is completely done in a stereotypical chick lit author style. Methinks this is all free marketing.

I think she started a new chapter in an important conversation but I also think she wants it both ways.

“…purportedly lighter “chick lit” fare.”

Purportedly? Really?

Yes, really. There are “chick lit” books that tackle serious subjects. People who claim that chick lit is any one thing including, “lighter fare,” aren’t well-read in the genre.

Oh, you meant actual subject matter? I took “lighter” to mean “not as well-written.” I’m pretty uninterested in a book’s subject, really. I care only about the telling.

I’m wondering– being a “serious reader”, shouldn’t the art itself supersede any assumptions I can make about it? Or shouldn’t I expect it to at least? If a book does get this SEX AND THE CITYish cover and marketing push, a zillion more people will theoretically read it. Wouldn’t someone notice if it’s actually a great book? I feel like you could put the Kardashian sisters on a Lynne Tillman book and I’d still eventually find it.

I’m not saying this weird marketing thing isn’t awful, mind you. They’re turning off as many people as they turn on.

Another side to the coin though: there’s a market for this marketing. That’s a huge problem, too.

[…] covers, chick lit, and women always exhausting themselves to prove they’re serious writers. I wrote about it on HTMLGIANT. I can summarize my thoughts in one sentence: We are really fucked so long as anything considered […]

I have two issues with Courtney’s argument here:

1- I’m not sure if I see a clear distinction between what she claims is “chick-lit” and what she claims is “women’s literature”. She claims that reading might be disappointed to learn that there’s too much “substance” in her plots, but from the synopsis of her new book it seems as if she’s relying on chick-lit tropes and plot points.

That said, I do think women’s lit exists. I’d define it as well-written prose that explores the complex, complicated issues that are solely specific to the gender (childbirth, motherhood, feminine maturity, social expectations); I’ve always thought of chick-lit as exploitative of modern culture and society’s gender roles in a very surface-level manner (Snooki). Since Courtney’s previous book was about an all-girl rock band’s climb to “the top” and is described as “a fast-moving story about friendship, resilience, and revelation,” can we just agree to call a spade a spade?

2- I don’t really like being this mean, but all of her previous book covers look like shit. I’m really interested to know what she’d think would be a better cover for a book about a 29 year-old female magazine editor whose tasked with managing an all-male staff.

But I think you raised a really great point, Roxane, and maybe my last point proves that we (or at least I) have to be more responsible. What I’m curious about, though, is whether you mean as consumers or as authors/editors/writer-jerks. Marketing teams are always going to look at trends and try to find a way to tap into what subconsciously appeals to us–it is, of course, their job to convince us buy their products. So what’s the solution here?

I think I feel pretty much the same way you do about this so I don’t have a whole lot to add except on a sort of related but maybe tangential point.

One thing that’s frustrating for me is the way I feel shut off from a lot of fiction by this marketing. There’s a cowardly part of me that doesn’t want to buy something that is “for girls,” and then there is also the honest, self-interested part of me that says, “Well, if they don’t think I would like this, if they didn’t mean it for me, they are probably right.” It’s a safe approach generally but sometimes it must be cutting me off from things I could love. A lot of writers I do like have had their books released in editions with chick-litted covers, which suggests other writers I might like are having the same experience, but I don’t know I would like them because I never saw them another way — I never had the chance.

Part of this is my internalization of misogyny, certainly — why should I care if something is “for girls? Why should that make it bad? — but also I think it reflects some genuinely shitty marketing on the part of these publishers. I have to think they are smart enough to find a way to invite women to read books without going the full chick lit. Actually that fourth Richard Yates cover strikes me as a decent stab at it — I’m not alienated by that. Probably the best way to invite women to read books without closing men out would be to take the books seriously, to love them genuinely, and to promote whatever pleasures they have to offer without diminishing those pleasures. Maybe they should publish women, and men who are comfortable with women, and let women know they are valued. The whole chick-lit thing — not the genre itself so much as the genre of marketing — seems like a way to avoid the effort of valuing writers and readers.

It’s a really good question to ask and think about, the way you presented it here is provocative. I think the deeper question is one of genre, yeah. It’s as though works written by women that are about friendship, work, romance and social nuances and have a sense of humor (hello how many works written by men make humor out of neurosis?) need to be tightly defined so that the wrong people don’t feel they need to read them.

One good example of really good “chick-lit” is “A Girl’s Guide to Hunting and Fishing” by Melissa Bank. The main characters in this book are writers and elements of NYC literary culture (as far as publishing houses, magazines, and lore) make its way in there.

This novel avoided the trappings of other “chick lit” covers perhaps because of the title? Feel there was some irony in that title. [http://www.amazon.com/Girls-Guide-Hunting-Fishing/dp/0140293248/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1317222991&sr=1-1]

Maybe the solution is for “chick-lit” writers to publish bigger. Thinking way way way more words and pages. Drop a 1000 page block into the world and then people will take you seriously.

Thinking, George Eliot’s “Middlemarch” has a very deft lightness to its style and a warm humor that permeates everything in it, yet is complex and explores serious (read: impersonal) themes. Despite its cute, picturesque drawing on its June 2011 cover, it is a political novel. [http://www.amazon.com/Middlemarch-George-Eliot/dp/1613820550/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1317222335&sr=1-1]

A good example of “lad lit” is “Bright Lights, Big City” by Jay McInerney. You can read this one in a few hours, it goes so fast (an admirable thing). However, there’s really not much depth to this novel.

http://www.amazon.com/Bright-Lights-Big-City-McInerney/dp/0394726413/ref=cm_rdp_product

Maybe someone can do a post on heralded novels that have depth, but are kind of dull or plodding to read? This seems like another way to approach a potential discussion going on here.

another way to read this is her three book deal is completed and harper wasn’t interested in a new deal, so she is going back to self-publishing.

I could have sworn that the name for the male-themed analogue to chick lit was “dick lit.”

My undergraduate thesis for Jaimy Gordon’s class at Western Michigan was written on this back in 2004. It’s been a problem for such a long time and is only getting worse. Google Pam Houston’s “Cowboys Are My Weakness” in image search for some shocking results. That book, if you haven’t read it, contains a lot of writing that is bold and tough and often about masculine adventures–grueling rafting trips, for instance. Many thanks for this post!

I really like chick lit.

1. This may have already been noted, but the tagline “but it takes a woman to run it” was actually the publisher’s idea, not necessarily Courtney’s; the title itself, I believe, is the author’s. 2. I do stand behind her, ultimately, in her choice, but that probably has more to do with my personal aversion to most of the books commonly known as ‘chick lit’ than anything else. I think of that as kind of a fatal brush for a female author to be tarred with. 3. I really like your point about the public image of most chick lit being just as much our fault, as readers. The publishers market these books this way for a reason, after all. And I realize that, given this, my last point is a problem. 4. That ‘lad lit’ article was very interesting as well, particularly the assertion that books marketed exclusively to men in that way, as in designed not to appeal to women at all, don’t tend to sell. 5. Booty Nomad, hahahaha.

Yes, I meant subject matter. There is, indeed, a market for this marketing or it wouldn’t exist. I’d love to start a conversation about that problem too. There’s a lot going on here.

Re: your second point, yeah, when I saw her previous covers, which very much seem like “chick lit” covers but not that well done, I wondered what she was thinking. Given the book’s plot, the cover seemed fairly appropriate. It might have been neat to do a cover with a woman on one end of a conference room table and a bunch of men in suits on the other end doing a tug of war but really, there aren’t that many options given the plot as I understand it. As for the solution, I firmly believe it starts by first not considering anything coded as feminine negatively, and then finding more intelligent, intuitive ways to market books. I do want to have a conversation about solutions because I think it’s important that we move forward with a problem-solving mindset or this issue will never change.

Do you have specific novels that are heralded and deep but dull and plodding?

I found Don Quixote (in English) – unquestionably “heralded” – to be “deep”, often “dull”, and mostly “plodding”. I think Vanity Fair is “deep”, “dull”, and “plodding”, as is The Prelude (the latter shimmering between “deep” and ‘shallow’).

One can admire and even approve of things that bore one in most moods. It’s less a matter of taste than of a tempermental condition for the possibility of taste.

If the packaging of books is taken away from marketers and left to, in this case, the women who write the books, then – whatever patterns emerge from the choices those women make – at least the covers will have been authored by the authors of the stories within. If some of those patterns are misogynistic, the thin edge of an address to that malignancy would be in the hands of those both suffering from and responsible (in this small way) for reproducing an institutionalized misogyny.

It is a circularity: to what extent does marketing generate its audience, and to what extent does an audience determine ‘success’ in marketing (by choosing from an array)?

Hey, not really or I would have to think about it. I was gonna say, “it’s a matter of taste” but then I read the comment below and wonder there could be more to it.

I’m less interested in works themselves being labelled in these terms as I am in the holism that would result in discussions of literature when they receive this treatment.

The distinction and varied merits can be a difficult thing to identify because sometimes when something is deep it sincerely does more than make up for a dull writing style or voice. DQ could be a good example of this (personally I wasn’t able to finish it, but was never able to admit to myself that it was dull. Even now I have trouble).

At the same time, writing can surface-riveting but be consumed too easily, like junk food, leaving little remaining. These are just qualities I have noticed and as with anything they can be used like tools.

I will say that I have noticed that writing that has a lots of thoughts

in its, dense thoughts, can feel more clogged to read than something

that has a balance of senses, feelings or varieties of meaninglessness.

But even that is hard to say cos sometimes thick prose is just operating at a

more abstract level, where it belongs. An example of that would be Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.”

In any case this all makes for interesting discussion.

I don’t think it’s quite right to say women writers resisting the label “chick lit” is internalized sexism. That’s part of it, sure, but I think what’s actually happening is a lot more complex. I don’t know that there’s a “marketable” name for all those Tyler Perry movies, but when serious artists like Spike Lee resist them, no one accuses him of internalized racism. In fact, part of what Lee resists about the Perry movies is that they reflect what Lee sees as *Perry’s* internalized racism. The internalized sexism label might be more accurately applied to women writers who said stuff like “I only write about men,” or “I don’t like to read about women characters.” To resist chick lit is not to resist women’s experiences but a *parody* of women’s experiences. I’ve often thought about a post I saw here within the last year or so–a male writer who said he’d bought Lorrie Moore’s A Gate at the Stairs, but “probably would never read it.” The cover of that book is in no way representative of all chick lit’s stock images; still, a male writer thought he might get bored when he read it. I’ve seen Moore called “domestic,” a grossly unfair label in my view, but the name-calling itself leaves me wondering just what in the hell women writers–writers of fiction, in particular, and writers who consider themselves serious artists–have to do to inch their way toward having their work called “universal” rather than “for women.” Go to war-? Then it’s the “woman goes to war novel.” Maybe they’re not calling us scribbling women anymore, but they might as well be. Maybe it’s the whole culture that’s a victim of internalized sexism. Internalized, externalized: I see it all the time.

I think it’s painting with broad strokes to say chick lit is a parody of women’s experiences. Just like with any genre there are interesting, thoughtful titles and those that are less so. I also don’t think the Spike Lee/Tyler Perry analogy works quite as well because of that. Tyler Perry isn’t a genre, he’s one creator and because of that it’s a lot easier to critique what he makes as a somewhat cohesive body. I think Roxane’s point comes from the fact that chick lit is a genre that not only is not afraid to come across as feminine, but flaunts it’s femininity by way of book covers and titles that scream THIS BOOK IS WRITTEN BY A WOMAN. I do think that at times that delves into parody (especially in terms of the marketing), but difficult to see anyone’s wholesale trashing of the genre as being a reaction to quality of writing. More likely it’s a reaction to the covers and the titles and their idea of the books, and that idea is that these books are hyper-feminine in a very mainstream way. Then again, I don’t know that I can blame people who have that reaction, because I generally shy away from titles that seem hyper-masculine. I tried to read a Tom Clancy book in high school once and that was pretty much the end of that for me.

I really don’t think you can make an analogy between chick lit and Tyler Perry films. Tyler Perry films are exploitative in a way that I simply don’t see in chick lit. I don’t find chick lit to be even remotely parodi and to characterize it as such seems inaccurate. I’d say that chick lit would be more akin to fantasy or wish fulfillment, but parody? No.

I guess it depends whose fantasy you’re talking about–certainly not mine. I think it’s painting in broad strokes to say those covers are “not afraid to come across as feminine,” when they seem to me deeply afraid to come across as fully human. Whether we blame that problem on the marketing people, the writers, or the readers doesn’t matter so much to me as does the gendered specificity itself; it seems to me there’s something deeply wrong with a culture that categorizes artistry on the basis of something so flimsy as what people wear and whom they want to sleep with. I’ve never actually seen a Tyler Perry film, but what I can glean from what you see on television and the internet suggests to me he’s more a businessman than an artist, which is not to say he lacks artistic aspirations. The same is true about women who volunteer for the chic-lit brigade; I’m sure–in fact I know–many of them are very good writers, and, for whatever reason, their subject-matter strikes marketers and/or consumers as specific to the experiences of roughly half the human race. It bothers me to think that something I thought was going to be a mere “post-feminist flash in pan” has become so mainstream people feel the need to defend it—as if the mere objection to the culture that creates chic-lit might threaten to rob us all of five seconds of high-heeled bliss. I for one would be fine without it.

Well, fantasy isn’t universal. Books don’t have to speak universally, do they? I think it’s sad that women want to distance themselves from feminine coding because our culture tells us that the feminine is weaker, less intelligent. I find them to be very human, nakedly human in fact, because they reveal something about us, perhaps something flawed, but definitely something true and no, not in a universal way, but those covers do speak to some women. Also, are you basically suggesting that women writers who write chick lit are “asking for it,” when their work isn’t well received or critically acclaimed? Certainly some women write chick lit as a marketing ploy but some, many, write these stories because that’s what they want to write. Tyler Perry is… terrible. He is terrible in a dark and disturbing way that chick lit is not. You’d have to see the movies to understand. Finally, I believe all literature should be defended, whether we’d be fine without it or not, even if I don’t like it.

I just don’t want to have to put on a clown suit for people to think I’m funny. If all those high heels and trays of champagne glasses are “coded” feminine, all I’m asking is why not change the code-? I–and people who think like me–can’t do it by ourselves, and every time someone markets or buys one of those “stock feminine” books the code becomes more firmly entrenched, and the rest of us have to try all that much harder to defy it. The writer’s position, on the other hand, is one I sympathize with–whether she’s writing genre fiction because “she wants to” or because she “wants to make money” or because she’s somehow fallen into a marketer’s trap is anybody’s guess; I’m just painfully aware every time I go to the bookstore I find more and more evidence the culture-at-large and what’s marketed as “women’s culture” in no way speaks to my own experiences. But that’s why we write, I suppose, and writers ought to take at least some responsibility for telling the truth about–and not simple reinforcing–the culture’s ills.

Rejecting feminine coding because of its stereotypical assumptions is problematic if the individual doing the rejecting actually believes that those assumptions are true. But if one rejects feminine coding–or any other kind–out of an awareness that those assumptions are abundantly false and an unwillingness to perpetuate anything about them, I don’t see anything sad about that, especially if the coding in question has been hanging around for too long already. I’m thinking of those periods when various social movements have advanced successfully by the reclaiming or celebration of codes associated with negative stereotypes–“Black is Beautiful” comes to mind, as does “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” as slogans associated with political reclamations that seemed to be at least temporarily very powerful–but in the case of the femininity stereotypes, I just don’t see it working all that well, for reasons that are difficult to pin down. Whatever the cause for the relative ineffectiveness of stereotype “reclamation” for women, I think that after several decades of efforts in that vein have hit the wall, as they do seem to have done, about all it illustrates to maintain the same old same old symbolism, pink, high heels, whatever, is a failure of imagination and a fearfulness about being perceived as unfeminine–which would be a manifestation of sexism itself, no?

Well–along the lines of what I posted to Roxane–the problem for me here is that women are taught to fear NOT seeming feminine; femininity is a policing mechanism for the conformity of women to a norm that is as limiting to them as the assumptions of masculinity are for men. So this “flaunting” is every bit as likely, if not a heck of a lot more so, to be signaling somebody’s insecurity–if not the writer’s, the publisher’s–as it is to be saying something positive about the feminine.

The feminine code is much broader than book covers would have us believe, and sadly our culture does not allow for that reality. Nonetheless, I don’t believe that certain aspects of the feminine code should be dismissed out of hand. Those codes are not the problem. It is how they are used against women and how they are used to constrain women that are the problem and I see that as a different (though certainly related) issue. Indeed it is difficult for many women to find their experiences mirrored in what they see in bookstores. That’s certainly one of the reasons I write, to add a different perspective to women’s experiences. I think it’s good, in some ways, that I can find experiences that don’t mirror my own. I don’t always need my reality reflected back at me. The problem is, of course, that oftentimes we don’t find our experiences in fiction not because there is so much diversity but, rather, because there is not enough diversity in expressions of what constitutes women’s experiences.

You make excellent points and I agree with much of what you say. Femininity isn’t any one set of codes and we are indeed having to fight the rigidity of femininity. That said, those assumptions about femininity aren’t always false. The phrase about throwing the baby out with the bathwater comes to mind.

I agree with that, but I think it’s also important to break down the notion that the only way a woman can be taken seriously is to tone down their femininity.

Though, as always, Roxane managed to express my feelings on the subject better than I did in her comment below.

I honestly think the solution is the one that the most successfully female writers of all time have used: publish under a name that could be mistaken for a man’s.

Harper Lee

J. K. Rowling

A. S. Byatt

ZZ Packer

George Elliot

Carson McCullers

A. M. Homes

P. D. James

and more

It does seem like a parody though, because the styling and image are so non-specific to the characters (and, coincidentally to the lives of all the women I know personally). Chick Lit covers are deadening in part because they’re all so interchangeably similar – – a very narrow idea of how it is to dress up or go out to meet your boyfriend / lover / date, even if I do, yes, love to dress up to go out.

That said, if the book reads like a magazine, then it makes sense for the cover to look like a page torn out of Cosmo or Elle. But if the book reads like Lorrie Morre, then the cover should reflect that.

Most important of all, good books should be objects of beauty. And chick lit covers are pretty fuckin ugly.

But do you think that the covers themselves feel like parody? Even if the books’ content may not be?

I think it depends. Clearly, some covers do become parodic (in the same way that when Hollywood hits on a successful idea, they release ten movies of the same ilk like disaster movies or the friends with benefits theme, etc). That said, it’s far too easy to make sweeping generalizations about this genre. People hear “chick lit,” and kind of lose their minds. They judge all chick lit as equal and such simply isn’t the case.

I like what you have to say. Makes me think about how we’re now defending the ability to appear universally Stepford Wife-ish, as if it’s a radical pro-girl stance. (Though I also agree with Roxane, in that we ought to celebrate appearing as girly as we like. But I don’t think the two points are really in opposition if they’re done honestly.)

Have you read Female Chauvinist Pigs, by Ariel Levy – – so funny and so good and a quick one-afternoon read that distills so many weird things about today. I can’t recommend it highly enough.It’s like we’ve kept the spirit of reclamation, but we’re using it to star in Mad Men.

S. E. Hinton. –but in what way is ‘passing’ a “solution” – other than as a capitulation?

Feminist Chauvinist Pigs was an interesting book. I loved some parts of it and didn’t love others but on the whole, I really like the ideas she worked through in that book. I actually wanted her to go into more depth than she did.

That’s not the solution. That’s capitulation. At best, it’s temporary and still doesn’t address the underlying problem. Sure we can do that until things get better, so to speak, but we still need to work at addressing the larger problem, or as I note, focusing on the disease and not the symptoms, focusing on a cure, not treatment.

Well, I honestly think that the author should be as close to invisible as possible. As malleable as the work. Let only the story speak.

And this is one way (? the only way ?) that readers glance at a name, think nothing, and then read the words of the work.

Initials are genuinely gender neutral. But your story will be very specifically yours.

Most people know J. K. Rowling or A. M. Homes are ladies. But magically they aren’t pigeonholed as ladies. And J. K. for sure is not temporary. She’s one of the richest / most successful woman who ever lived.

Yeah, I could have read like three more of them. But it’s so easy to recommend a book that you can read in an afternoon, and I really like that. I feel I’ve sold a lot more to people who wouldn’t really be open to a big fat one. And I think she did that on purpose.

It’s interesting, though, to talk pretty specifically about the covers. The contents of Polly Courtney’s books are the same, whether they’re sporting covers that signal “award-worthy good book” or “Cosmo-esque beach read.”

There’s another thing, too: in bookstores, the better the cover the better the book’s visibility, because staffers will turn that sucker faceout every time.

But yes, I agree: chick lit makes people loose their minds. Wouldn’t it be nice if it were just one category choice out of many for the author, and not a corset?

It is interesting and I’m happy (eager even) to talk about book covers. I think, as I noted elsewhere in this thread, that Courtney is really playing both sides against each other. Part of me definitely believes that if the book is good enough, it can overcome the cover. The oddest thing about this issue is that the cover is just a bad book cover, not because of the high heels or the legs or any of that but because…it’s not a great picture and the colors are ugly etc. I look at that cover and think, “stock photography.” That cover is not even that chick lit esque, you know, and that makes her argument all the more frustrating and reinforces my opinion that while this is an important issue to talk about, she’s kicking a hornet’s nest to drum up publicity.

It would be very nice if it were just one category. I hope some day it will be.

That’s a fair point and goal: to de-identify the author so the work can emerge without identity-based preconceptions.

But what you’re pointing out is not a partial erasure from the perspective of exerting the strength to discard preconceptions – ‘I don’t need people to know me, just to read me’ – , but rather, from an acceptance of the wisdom of catering to a stupid preconception.

As a stop-gap: okay; books’re more likely to get into condescending hands, perhaps transformatively.

–but as a standard to be conformed to, and so re-inforced, for the sake of expedience? for how long??

[…] thoughtful article about chick lit by Roxane Gay over at […]

I don’t know for how long, and I do see your point – – but there is a truth here: it works. And it also gets to something else, as well: the age, class, ethnicity and experience of the characters & story, the verisimilitude, are taken as a given when readers see the author’s abbreviated name and think nothing.

I guess what I hope for is not an acceptance of a stupid preconception, but an utter refusal of that preconception. I’m not interested in what you think of ladies. And if my name goes both ways, you know nothing. …Until I get famous.

But the truth is, these days I think I’d like to publish each story under its own pseudonym. Real Self is so embarrassing, isn’t she?

[…] thoughtful article about chick lit by Roxane Gay over at […]

[…] let us start with Roxanne Gay, who tries to scrabble together an overview of a question that recently rippled through the […]

[…] job. That we wonder what it means when a girl relates to a science fiction book and question the validity of feminized book covers speaks to the hazy categorizations of genre versus gender that remain engrained even in book […]