Behind the Scenes

Making Games: Stumbling from Design to Debut

We had one semester to make a game.

The class was through the California Institute of the Arts’ Integrated Media department, which styles itself a meeting ground for complimentary métiers. It met each Monday morning in the school’s chilly bowels for a scant two hours – just enough time to write something on a chalk board, high-five or disagree, and then not see each other for a week. It’s a wonder we made anything at all, let alone debuted a prototype at a crowded convention called the Maker Faire three hundred miles north. What we brought is not what we intended – a partially miscarried hybrid of real and vestigial features – but game development, like any collaborative undertaking, isn’t a straight shot.

Our group was nigh-ideal: five graduate students and one talented BFA, no one from the same background. There was a programmer, a theater set designer, two breeds of visual artist, an ambient musician, and myself – the writer. Previous groups had gone the techy route, rigging RC cars with baby monitors, but we wanted to straddle multiple media – to build a game that played in physical spaces, drew from digital content, and answered to verbal interaction. By the end of our first class we had a draft.

“I’ve never seen a game come together so quickly!” the class’ instructor announced. “It’ll be great at the Maker Faire.”

That’s the thing, though – you can chart a voyage to the moon, but landing on the surface is another thing entirely. High-concept ambitions are irrelevant until you see them through.

Our design on paper was a monster, something you would murder if you found it in a lab. The hulking Franken-game included real-world installations, app-based digital avatars, RPG-esque progression, and heavy narrative content.

Sounds rad, right? Proposals often do.

The game’s basic idea was that Atlantis vanished from the world after losing texts from its library – that, without narrative, its culture lacked meaning, and “history rejected it as we’d reject a madman in the streets.” We envisioned players starting in a decorated tent called “The Locus,” downloading the iPhone app for character progression, and then visiting three different locations across the Faire to play verbal mini-games. The results of these contests would be the lost Atlantean texts, and returning them to The Locus would recover the missing city.

Beneath this grand ambition was the stark, essential fact that our mini-games were no fun to play. They didn’t work, really – felt tacked on and arbitrary – despite being the heart of the game. They were our core mechanic, everything else just window dressing, yet we took them for granted. Development happened backwards: our scope was so big-picture that the vital parts came last. We had a catalogue of features we enjoy but nothing to hold them up.

Weeks went by, and attendance got shaky. I began to doubt. People disagreed on what should be our emphasis, who the game was for, and what role story should play. The Maker Faire drew closer.

And then we turned it on.

Features started dropping like the heads of French nobility. The best of our mini-games became our core mechanic, restructuring from speech to cards. Atlantis swapped out for an original setting: The Library of Mythos, a prim and frantic despot in the throes of sabotage. Soon we were filming our opening cinematic, harvesting material for gameplay, and talking with printers.

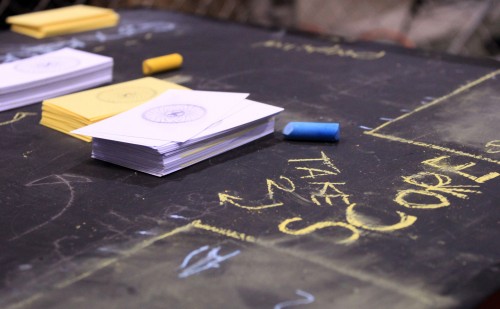

The game now worked as follows: players would draw cards containing language fragments – stems, words, or sentences, depending on the mode – and combine them to make new content. “Astr-” and “-ocracy,” for instance, could pair to form “star government,” while words and strings of text combined for longer stories. Summing the point values of cards determined victory.

It was a casual language game – nothing over-the-top, but highly modular with strong emergent content. The narrative supported gameplay but didn’t overwhelm it, establishing political stakes. We’d arrived somewhere new: Mythos, as we called it, was one solid idea without frilly accessories. Details needed polish, but the game’s basic concept – its vital core mechanic – carried all the weight.

Soon it was time to debut.

The Maker Faire – held yearly in San Mateo and New York City – is a giant congregation of DIY technology. Engineers, artists, game developers, and craftsmen of random trades meet to show their work, networking and selling to crowds. 3D printing was all the rage this year, robotics as popular as ever. One guy played guitar with tesla coils.

Think of it as the Burning Man of Silicon Valley. In fact, I’m pretty sure the dragon-truck with torches on its ramparts drove straight from the desert.

We arrived pre-crowd with all the other “makers.” Our game conveyed its story through a narrative cinematic, so we brought a big tent and a projector for our booth. The gameplay was still supposed to happen elsewhere in the Faire, making the booth only a starting point – a film screening facility to introduce new players. We thought it no big deal that the enclosure consumed roughly four-fifths of our allotted space; the awkward little channel left between muslin walls and chain link could hide all of our stuff.

Or, of course, host the entire game.

Crowds appeared and turned the Maker Faire to wilderness. It was immediately clear that dispersing to three locations would only dilute our presence, adding little meaning in return.

“Let’s keep gameplay here,” we agreed. “Nobody’s going to wander around to find our little stations – there’s too much here to see.”

Except, in our case, all they saw was our tent. The thing refused to ventilate, heating like an outhouse. The film’s ambient soundscape droned like a hipster rift in space-time. Our play area – just a few tables and some cushions – struggled now in what space it could find.

“NOBODY LOOK AT OUR AWFUL TENT,” I wanted to scream at passersby. “WE HAVE A GAME OVER HERE.”

Parents lifted the tent flaps with visible confusion, ushering their children along. Occasionally some brave mother would deposit her young inside, and we would get to watch three eight-year-olds blink at a lopsided screen. The film was just looping on its own, insanely. Nobody could hear the words. Almost immediately we abandoned the entire narrative, directing anyone with passing interest to the tables and the cards. “There’s a story, but ignore it. This game is actually fun.”

And it was.

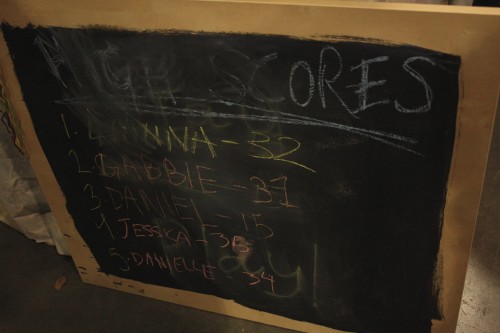

Kids around the twelve year mark had a blast inventing words, perfectly situated between grammatical stability and vocab exploration. I watched a father play his daughter – watched him watch her exploring English’s anatomy – and had to apologize when he tried to buy the game. The other modes of play – sentence and paragraph-creation – appealed to older groups by providing a constraint, by tossing them material to tell an easy story. Creativity loosens when you have something to work with.

So though we made mistakes, and that tent will haunt my dreams like a garbage spirit animal, the game that we produced held up. It wasn’t our original design – and certainly isn’t complete – but that may be the point: development continues through debut, constantly incorporating feedback. The Maker Faire was basically a giant public play-test, a chance for us to gauge a random spread of demographics. We learned where our game excelled and where it didn’t – in essence, seeing it for the first time.

***

James Pianka writes fiction, critical theory, and vocals for heavy music in Los Angeles, CA. He’s midway through his MFA in Writing (Integrated Media) at the California Institute of the Arts, and wants to take games to their storytelling potential.

James Pianka writes fiction, critical theory, and vocals for heavy music in Los Angeles, CA. He’s midway through his MFA in Writing (Integrated Media) at the California Institute of the Arts, and wants to take games to their storytelling potential.

Tags: James Pianka, Maker Faire, making games

this sounds like an awesome game! i invented a similar-ish card game to try to teach English vocab to mostly students from China with very little English experience during a summer camp class that the camp called “The History of the English Language for SAT Prep” (yeah, haha)… it was the only thing everybody unanimously liked about the class i think

and i love that core mechanic chart… would be fun to apply that to any given poem/story

how did you figure out the points values of the cards?

Completely arbitrary assignment. It was definitely the game’s worst feature, and the first get redesigned. We’re trying out something qualitative now.

sweet // seems like it would be cool if there were different modes and players could choose which mode to play in // like refer to Chart A for one set of point values or Chart B for a different set // seems like the assignment of point values is the most interestingly ideological part of the mechanic, weighing language against itself and highlighting the arbitrary nature of such weighing // like that hilarious/ridiculous/amazing poetry assessor from a few days ago // or anyone who played the game could DM up their own points system if they wanted to // thereby reflecting their feelings/beliefs about language

Thanks for posting this! I’m planning to write more here about how game design relates to writing.

Are you familiar with Mark Rosewater’s article “Ten Things Every Game Needs“? Might interest you.

Cheers,

Adam

[…] Pianka writes about the process of designing a game for debut at the Maker […]