Craft Notes

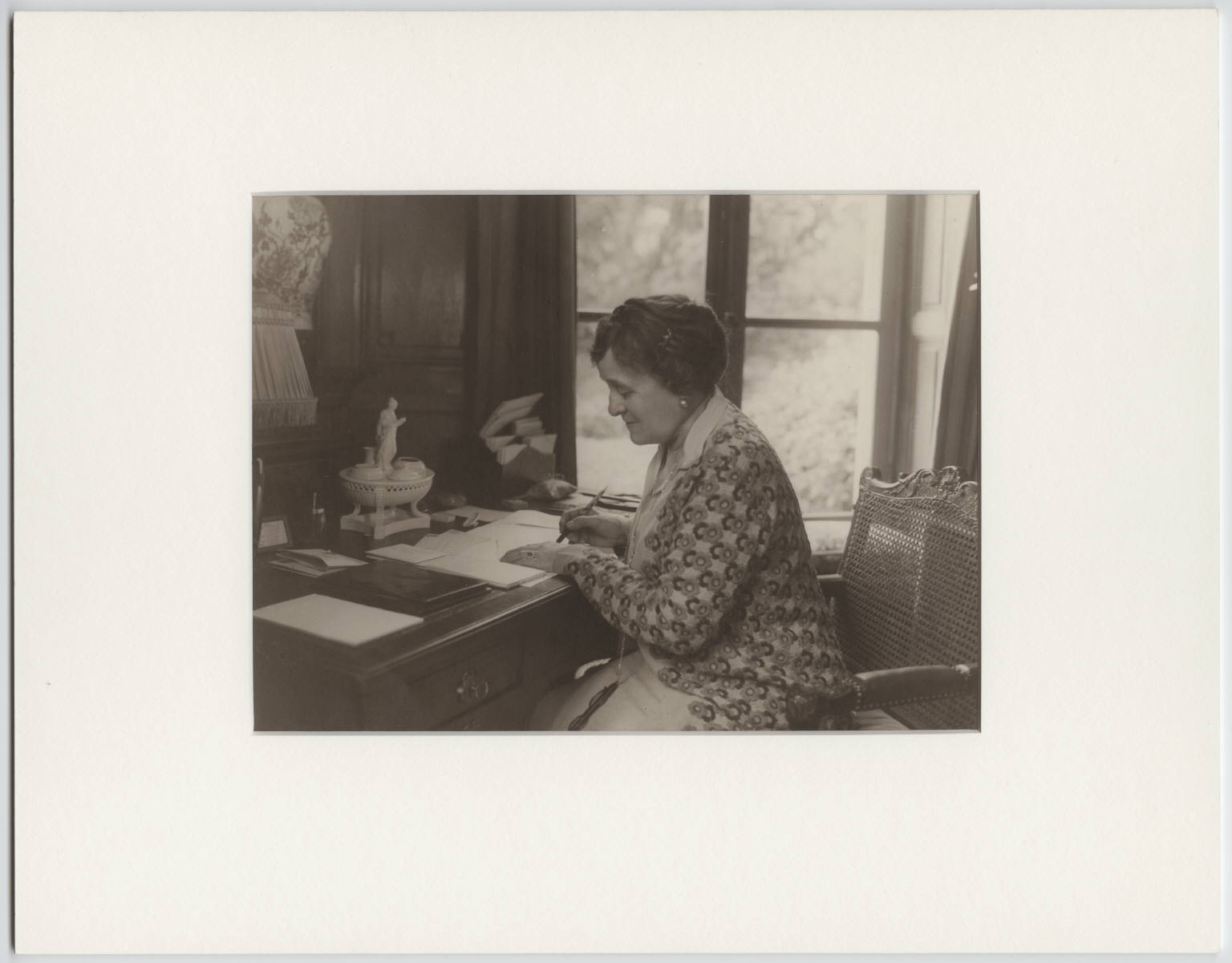

Class Is in Session With Professor Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton is one of my favorite writers. Her stories are timeless and elegant and if I had to be trapped somewhere with only one writer’s books for the rest of my life, I’d probably choose the complete works of Edith Wharton.

I’ve been thinking about Edith a great deal lately because I’ve been having a lot of self-doubt about my writing for a number of reasons, few of them rational, all of them frustrating. The Internet is great but it’s also terrible because you know, all the time, what everyone else is doing and it’s easy to lose sight of writing itself as what matters most. It’s not hard to fall into the trap of losing confidence in what you do as a writer and/or trying to keep up with the literary Joneses by writing outside of your comfort zone to respond to the literary zeitgeiest. The older I get, the more I realize that while you can and should grow and challenge yourself as a writer, you can only be who you are. Sometimes, like many writers, I lose sight of that. I recently consoled myself with Age of Innocence and Wharton’s amazing short story, “Copy: A Dialogue.” Then I read Wharton’s The Writing of Fiction, a slim but rich volume of writing on writing. Wharton’s insights are sharp, timeless, and truly invaluable.

I had no way of knowing but this book was exactly what I needed to remind me about what I should be doing with my writing. I particularly appreciated her counsel on novels that are focused and character driven. Edith totally set me straight.

I also realized many of the conversations we have about contemporary letters are the same conversations that were had when the book was published in 1924. Wharton offers opinions on writing education, genre fiction, literary realism, “magazine stories,” the short story, novels, the work of the critic, character versus plot, readability (hello, Winterson), structure, the nature of art, and so much more. She’s unafraid to offer opinions on how things should be done and her arguments are always compelling. I don’t know why it took me so long to read this book but it is required reading. In addition to the valuable advice, the book is so elegant and witty. I laughed out loud over and over.

Wharton demonstrates a fluent understanding of both her contemporaries and her predecessors and she offers strong opinions—Jane Austen, impeccable, Thomas Hardy, not so much. She really doesn’t care for Hardy. She holds the French and Russians in high esteem and the last chapter is dedicated to the charms of Proust. Balzac, Thackeray, George Eliot and Tolstoy should be read repeatedly. This book showed how the work of the fiction writer is not only to create fiction but also to consume fiction and be able to hold forth on matters of craft. Not for nothing, Edith was also an interior designer. Old girl could arrange a room.

I could have easily transcribed the entire book but I selected the choicest bits (in a book where everything is choice) for your delectation.

On a the challenges facing fiction:

The distrust of technique and the fear of being unoriginal—both symptoms of a certain lack of creative abundance—are in truth leading to pure anarchy in fiction, and one is almost tempted to say that in certain schools formlessness is now regarded as the first condition of form.

Another unsettling element in modern art is that common symptom of immaturity, the dread of doing what has been done before; for though one of the instincts of youth is imitation, another equally imperious, is that of fiercely guarding against it.

True originality consists not in a new manner but in a new vision.

On teaching fiction and young writers:

One is sometimes tempted to think that the generation which has invented the ‘fiction course’ is getting the fiction it deserves. At any rate. it is fostering in its young writers the conviction that art is neither long nor arduous, and perhaps blinding them to the fact that notoriety and mediocrity are often interchangeable terms.

On the necessity of experience:

As to experience, intellectual and moral, the creative imagination can make a little go a long way, provided it remains long enough in the mind and is sufficiently brooded upon. One good heart-break will furnish the poet with many songs and the novelist with a considerable number of novels. But they must have hearts that can break.

On balancing vision and talent:

Perhaps more failures than one is aware of are due to this particular lack of proportion between the powers of vision and expression. At any rate, it is the cause of some painful struggles and arid dissatisfactions; and the only remedy is resolutely to abandon the larger field for the smaller field, to narrow one’s vision to one’s pencil, and do the small thing closely and deeply rather than the big thing loosely and superficially.

On defining form and style:

Form might perhaps, for present purposes, be defined as the order, in time and importance, in which the incidents of the narrative are grouped; and style as the way in which they are presented, not only in the narrower sense of language but also, and rather, as they are grasped and coloured by their medium, the narrator’s mind, and given back in his words. It is the quality of the medium which gives these incidents their quality; style, in this sense, is the most personal ingredient in the combination of things out of which any work of art is made.

Last week, I wrote about writing that matters and a commenter asked, “What is writing that matters?” Edith takes up this question quite reliably:

It is useless to box your reader’s ear unless you have a salamander to show him. If the heart of your little blaze is not animated by a living, moving something no shouting and shaking will fix the anecdote in your reader’s memory. The salamander stands for that fundamental significance that made the story worth telling.

There are subjects trivial in appearance, and subjects trivial to the core; and the novelist ought to be able to discern at a glance between the two, and know in which case it is worth while to set about sinking his shaft.

A good subject, then, must contain in itself something that sheds a light on our moral experience. If it is incapable of this expansion, this vital tradition, it remains, however showy a surface it presents, a mere irrelevant happening, a meaningless scrap of fact torn out of its context.

On plausibility and the short story:

The greater the improbability to be overcome the more studied must be the approach, the more perfectly maintained the air of naturalness, the easy assumption that things are always likely to happen in that way.

It is never the genii who are unreal, but only their unconvinced historian’s description of them.

The moment the reader loses faith in the author’s sureness of foot the chasm of improbability gapes. Improbability in itself, then, is never a danger, but the appearance of improbability is…

On horror:

Quiet iteration is far more racking than diversified assaults; the expected is more frightful than the unforeseen.

On the unrealistic protagonist:

They [protagonists] are his [the writer’s] in the sense of tending to do and say what he would do, or imagines he would do, in given circumstances, and being mere projections of his own personality they lack the substance and relief of the minor characters, whom he views coolly and objectively, in all their human weakness and inconsequence.

On the novel versus the short story:

The chief technical difference between the short story and the novel may therefore be summed up by saying that situation is the main concern of the short story, character of the novel; and it follows that the effect produced by the short story depends almost entirely on its form, or presentation.

On technique and style in the short form:

By all means let the writer of short stories reduce the technical trick to its minimum—as the cleverest actresses put on the least paint; but let him always bear in mind that the surviving minimum is the only bridge between the reader’s imagination and his.

On this point repetition and insistence are excusable: the shorter the story, the more stripped of detail and “cleared for action,” the more it depends for its effect not only on the choice of what is kept when the superfluous has been jettisoned, but on the order in which these essentials are seth forth.

Most beginners crowd into their work twice as much material of this sort as it needs.

True economy consists in the drawing out of one’s subject of every drop of significance it can give, true expenditure in devoting time, meditation and patient labour to the process of extraction and representation.

On structure:

Of the short story, on the contrary, it might be said that the writer’s first care should be to know how to make a beginning. That an inadequate or unreal ending diminishes the short tale in value as much as the novel need hardly be added, since it is proved with depressing regularity by the machine-made “magazine story” to which one or the other half a dozen “standardized” endings is automatically adjusted at the four-thousand-five-hundredth word of whatsoever has been narrated.

About no part of a novel should there be a clearer sense of inevitability than about its end; any hesitation, any failure to gather up all the threads, shows that the author has not let his subject mature in his mind. A novelist who does not know when his story is finished, but goes on stringing episode to episode after it is over, not only weakens the effect of the conclusion, but robs of significance all that has gone before.

On dialogue:

Narrative, with all its suppleness and variety, its range from great orchestral effects to the frail vibration of a single string, should furnish the substance of the novel; dialogue, that precious adjunct, should never be more than an adjunct, and one to be used as skillfully and sparingly as the drop of condiment which flavours a whole dish.

The use of dialogue in fiction seems to be one of the few things about which a fairly definite rule may be laid down. It should be reserved for the culminating moments, and regarded as the spray into which the great wave of narrative breaks in curving toward the watcher on the shore.

The object of dialogue is to gather up the loose strands of passion and emotion running through the tale; and the attempt to entangle these threads in desultory chatter about the weather or the village pump proves only that the narrator has not known how to do the necessary work of selection. All the novelist’s art is brought into play by such tests. His characters must talk as they would in reality, and yet everything not relevant to his tale must be eliminated.

On the necessary length of a novel:

The length of a novel, more surely even than any of its other qualities, needs to be determined by the subject. The novelist should not concern himself beforehand with the abstract question of length, should not decide in advance whether he is going to write a long or a short novel; but in the act of composition he must never cease to bear in mind that one should aways be able to say of a novel: “It might have been longer,” never: “It need not have been so long.” Length, naturally, is not so much a matter of pages as of the mass and quality of what they contain. It is obvious that a mediocre book is always too long, and that a great one usually seems too short.

On rules for writing:

General rules in art are useful chiefly as a lamp in a mine, or a handrail down a black stairway; they are necessary for the sake of the guidance they give, but it is a mistake, once they are formulated, to be too much in awe of them.

If no art can be quite pent-up in the rules deduced from it, neither can it fully realize itself unless those who practice it attempt to take its measure and reason out its processes.

On pigeonholing writers:

The very critics who extol the versatility of the artists of the Renaissance rebuke the same quality in their own contemporaries; and their eagerness to stake out each novelist’s territory, and to confine him to it for life, recalls the story of the verger in an English cathedral, who, finding a stranger kneeling in the sacred edifice between services, tapped him on the shoulder with the indulgent admonition: “Sorry, sir, but we can’t have any praying here at this hour.”

Class dismissed.

Tags: Edith Wharton

“More than that, I realized that many of the conversations we have about contemporary letters were the same conversations being had when the book was published in 1924.”

Yes. Very true.

An interesting follow-up to this post would be how writers like Wharton, Eliot, and Austen are often unfairly stereotyped as “boring and uptight” by contemporary writers. Nothing could be further from the truth.

“House of Mirth” is my favorite Wharton novel. Please, someone tell me what’s “boring” or uptight about Lily Bart?

Good, refreshing post.

Thanks. People who consider writers like Wharton, Eliot, and Austen (what a triumvirate), boring and uptight, don’t… know how to read.

(sorry for the tangent…nerd alert)…

I think contemporary writers often assume they can’t learn style/form from reading “classic” writers.

My humble, personal take: sometimes, reading older work is freeing for the writer, who take bits and pieces to apply to his own work. The writer also begins to understand contemporary style better, because he can see its evolution and is no longer reading contemporary work in a vacuum.

Fran Lebowitz makes great points in this video about how Austen (and you could probably include Wharton here too) is popular because she’s so often misread:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujjJlT9cCts

I often use a related video from the same series from Cornel West in my classes–it gets students excited about literature that they’re often suspicious of from jump:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHZGqnI8Gow

[…] Professor Edith Wharton teaches class at HTML Giant. […]

i don’t think “notoriety” is interchangeable with “mediocrity”; rather, i think a notorious writer is more often distinctive/”good” in a way that is unfamiliar and thereby threatening and confusing to many, causing them to dismiss it or to eventually come to see it. the difference between an aesthetic achievement and a disruption-in-the-literary-community is somewhat blurred to me; i’m thinking an “interesting”/”good” artist is a threat to the lit community status quo; their work is a challenge, not necessarily in terms of complexity/comprehension, but in terms of its status/perceived impact/perceived import as a work of art in a community of readers and writers. it seems like many of those we now consider great writers were once notorious, controversial, much-argued-over, and sometimes even banned in their day. as a writer i would consider it a good sign if some people were to hate my writing and/or dismiss it.

some of these rules of wharton’s don’t seem helpful to me unless one wants to write like wharton. if i was to ever find myself a teacher of writing or writing about the craft of writing in an essay, i wouldn’t give limiting rules to a writer, especially rules that have no logical basis and/or have been broken by many many revered writers. in a classroom setting, i would predict–with no evidence–that the students in whom i’d be most interested would be students who wouldn’t want me to give them arbitrary-personal-bias masquerading as sage writing wisdom; and so, wanting to please those students, i wouldn’t do that.

Edith’s rules are a great place to start. She herself acknowledges that rules are a guide, not a Bible. I’d also say her rules in no way dictate that writers should write the way she writes. I get wanting to rebel and be controversial and not finding Edith’s ideas useful. I shall continue to find Edith’s counsel extraordinary.

Easier said than done. Teachers in the arts have to take positions at some point. You can’t run always a class as some timid facilitator.

“[I]nterchangable” is qualified by Wharton as “often”.

–so one could argue whether “notoriety” for the sake of “notoriety” happens more “often” than “notoriety” rises naturally around a genuinely “new” voice that challenges simply because there’s something really novel about it – Wharton’s view – , or that the opposite order happens “more often” – yours – . Certainly there have been some (many?) artists who’ve gone from ‘rank outsider; practically an art criminal’ to ‘canonical; an example imposed on young artists of what not to rebel against’.

–but more of these “controversial”-then-“great” artists than “controversial”-then-untalented-and-forgotten artists?? . . .

Anyway, I think what’s important is to rescue the kernel of usefulness from Wharton’s perhaps-stuffy conservatism: the effort to impose scandal is “often” indisciplined (at the expense of clarity and force) to the point of preventing that effort from making accurate or even entertaining criticism of what it would scandalize, much less a pleasurable or genuinely challenging experience for an audience.

“Notoriety” which is almost only self-gratifyingly notorious–I think that’s what Wharton is warning against, in perhaps a genteel get-off-my-lawn tone.

The word “often” is important in the quote you’re referring to: Wharton isn’t stating that a notorious or controversial work is, by definition, mediocre. Instead, I would suggest she’s implying that artists who perceive themselves to be controversial, or revolutionary, or “threat(s) to the lit community status quo” are often not nearly as dangerous or forward-thinking or unique as their hype.

Obviously, countless great works were controversial in their time, we could limit ourselves to Grove Press alone and list a dozen titles fitting that description. “Notoriety,” however, is extra-literary. It’s a posture. I agree that it’s a good sign if a certain proportion of readers dislike a work, that’s an indication the writer stuck their neck out and took some risks. It’s a bad sign, however, if the author assumes that a negative read is automatically the result of the reader not-getting it or being too set in their ways or being afraid of edgy material. Most omnivorous readers are down for everything – up until the point they begin to suspect the author is wasting their time.

Also, when an author tackles the subject of writing, I’m not sure they’re actually trying to put together a “how-to” manual; rather than “rules,” I read these entries as “reflections.” While some of Wharton’s opinions relate more to her own tradition, I don’t think they’re meant to be proscriptive in any way.

Why is the “unrealistic protagonist” quotation doubly quotation-marked? Was Wharton quoting someone else?

No. I just clicked the block quote button twice accidentally.

Okay, seriously, how are we coming with the flashing “deadgod’s typing something” light that Alan proposed?

One “rule” that would attract some resistance – at least from a reader! – is one that you’ve quoted her calling “fairly definite”: that dialogue “should be reserved for the culminating moments”.

I like the image of dialogue being “spray into which the great mass of narrative breaks” – on the reefs and strands of decision and conflict – , but there are plenty of other effective uses of dialogue.

–as well, of course, as the case of fiction which is deliberately inutile or disruptive of ‘usefulness’ as a criterion or mode of reception. ‘Experimenting’ with rules as rules (as opposed to questioning particular rules as effective rules) might be something Wharton doesn’t accept as “art” or simply doesn’t care about.

That may be but I hate dialogue so her thoughts on dialogue may well be my favorite of her reflections.

She has thoughts on experimentation and she does accept it as art. I had to limit myself or I would have transcribed the entire book.

You hate reading dialogue or writing it? Expert dialogue is a tremendous joy to read (for me), because it intensifies or nails or whatevers a fictive immersion in the world of that action, those characters. –but it can be a bitch actually to say – by writing it – what people are saying in one’s story. . . . You hate both?

ha ha ha giddyap slow poke

I do not care for either. When it is well done, I recognize the merit and there are some lovely dialogic moments in fiction but in general, I don’t care for dialogue as a reader or writer to the point of hatred.

That hype and/or self-hype in the manner of “notoriety” might be obscuring a lack of danger or freshness – that such obfuscation is “often” a reason for hype and/or self-hype – is a good way to put it.

Wow. Can’t wrap my head around this.

You don’t need to defend your reasoning, but you’re kind of like a painter who hates green.

I have no intention of defending my reasoning. Thank goodness I have so many other colors available in my palette.

amazing, as always.

This is all really fantastic, but this is “hell yes,” fist-pump worthy: “One good heart-break will furnish the poet with many songs and the novelist with a considerable number of novels. But they must have hearts that can break.”

Fabulous stuff. I must read The Writing of Fiction ASAP.

If you’re writing fiction there aren’t THAT many colors in the palette. There’s dialogue and there’s exposition. That’s pretty much it.

What I don’t get is that you write character-based fiction and dialogue is the tool most advantageous for character work.. Dialogue brings out character faster and more effectively than exposition ever could. It tends to take the story in unexpected directions. it does wonders for pacing and gives the reader a break. Makes you come across as, I don’t know, stubborn?

I use dialogue all the time. I just dont like it. Jesus.

Ironically, the phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” was originally in reference to Wharton’s family (born Edith Newbold Jones).

Wharton doesn’t mean “notoriety” in the sense of being scandalous or controversial. She simply means fame.

I recently learned that and I find it to be such a delightful piece of trivia.

**NERD ALERT***

Did you know that the real-life Joneses that everyone was trying to keep up with were actually the family of Edith Wharton (born Edith Newbold Jones)? Edith Wharton was, quite literally, THE literary Jones.

I realize you may have known that already, that you may have included that clever reference to the “literary Joneses” because you knew that, but I had to say it, just in case…

I did know and inserted that reference to be clever hahaha. I like to amuse myself. It is still worth being said again. Edith is everywhere.

Oh, I see now, someone else beat me to this comment. Darn. ;-)

That’s probably so; almost the next thing she says is to refer to “writers indifferent to popular success“, and the paragraph ends up returning to a meditation on “‘Inspiration'”, on how generally to coax a spark to kindle a substantial flame (and not simply in the case of being adventurous or naughty).

‘Scandalous, controversial’ has been a strong sense of “notorious” for as long as ‘notable generally’ has been meant (both recorded mid-16th c., according to the OED); “notoriety” was an explosive synonym to choose for mere ‘fame’! –and it was an interesting turn for the conversation to take.

–

What do you think about fame and mediocrity being “often interchangeable”?

Painters CAN hate green.

I’ll have to look at this book again because I’ve read almost everything of hers including The Decoration of Houses. Wharton has had a huge impact on my career as an author. Of my twenty-one books, three

have EW connections: The Edith Wharton Murders; a book studying shame

in her life and fiction, Edith Wharton’s Prisoners of Shame; and a reply

to The House of Mirth: Rosedale in Love.

[…] Reader and trying to figure out how ready I am for NaNoWriMo. Oh, and I’ll leave with this: Class is in Session with Professor Wharton. Category: NaNoWriMo, Writing Tags: edith wharton, on writing, stephen king, writing […]

[…] Roxane Gay shares her thoughts about why Edith Wharton’s wisdom is timeless. This entry was written by crtriantos, posted […]

This was wonderful! Thanks you for posting this.

[…] for Vol. 1 Brooklyn and Jason Norman interviewed me about Tiny Hardcore for LitStack. I shared some science on Edith […]

[…] Class Is in Session with Professor Edith Wharton – Writing tips from the classic author, many of which are as helpful and pertinent today as they were when she wrote them. […]

[…] as an example. I can fanatically invest in Edith Wharton’s ideas about writing, as reproduced here by Roxanne Gay: find them helpful, insightful, inspiring. But Wharton herself warned against […]

Loved this little exchange and the “Jesus” at the very end. Sorry to break in! But I so empathize with Roxane coming from a different viewpoint: the foreign writer (English not my first language). As a reader I’ve never liked dialogue in any language. As a writer, it has taken me years to not be scared of it—now, like Roxane “I use dialogue all the time. I just don’t like it.” But when I use it, I use it sparingly (hence I feel enormously gratified by Wharton’s comment) and try to make it disappear in the story, to turn it into something quite different from “speech”. Looking at the novels of Thomas Mann (cp. “Magic Mountain”) or Dostoyevsky (cp. “The Idiot”) is quite instructive in this context because their novels contain a lot of dialogue that does not feel that way to the reader: someone is always talking, but this is not speech or dialogue, it’s voice. — In general terms thank you for bringing this book by Edith Wharton to my attention: I’m really enjoying it enormously.

[…] have a “female problem“? I’m not sure but he best back up off my girl Edith. We KNOW how I feel about Edith. More on this soon but in the interim, Victoria Patterson at the Los Angeles Review of Books, has […]

[…] is so crisp and precise. Reading her makes me want to be a better writer. Last October, I read a great compilation of lines from Edith about writing, and this was one of my favorites: Perhaps more failures than one is aware of are due to this […]

how to get free gems for dragon city

Class Is in Session With Professor Edith Wharton | HTMLGIANT

[…] to start a Literary Magazine Club and we sure tried to make a go of it. I wrote about my homegirl Edith Wharton, sentimental women’s writing, interviewed or reviewed talented writers, gave space other […]

[…] (h/t: Roxane Gay) […]