I start out endeavoring to write about those things I know; those authors I know; those films I know; those artists I know, because the chance of publishing something online and the rest of the world instantly knowing more about it than me simply isn’t weighed in my favor, so I want to start with something I know. Obscurity can work in my favor here. Choosing to review, say, Self Portrait by Man Ray will prove far less disputable than another slant on the terrifying depths of the sentences in Infinite Jest; so I may be wise to look to those lesser-discussed works on my bookshelf considering derision isn’t something I enjoy. Furthermore, and aside from obscurity or the arcane, I’m going to want to focus on the personal elements of the topic as opposed to those more general observations ever-present in every other publication on earth. This isn’t a critique of Mad Men for The New Yorker, this isn’t my attempt to reconcile the efforts of Frank Ocean as measured against the palpitations of James Brown, this is something different, and personality shouldn’t hide away at this most pivotal moment in my life as a hack critic postulating endlessly with cheap literary fiction tricks.

I start out endeavoring to write about those things I know; those authors I know; those films I know; those artists I know, because the chance of publishing something online and the rest of the world instantly knowing more about it than me simply isn’t weighed in my favor, so I want to start with something I know. Obscurity can work in my favor here. Choosing to review, say, Self Portrait by Man Ray will prove far less disputable than another slant on the terrifying depths of the sentences in Infinite Jest; so I may be wise to look to those lesser-discussed works on my bookshelf considering derision isn’t something I enjoy. Furthermore, and aside from obscurity or the arcane, I’m going to want to focus on the personal elements of the topic as opposed to those more general observations ever-present in every other publication on earth. This isn’t a critique of Mad Men for The New Yorker, this isn’t my attempt to reconcile the efforts of Frank Ocean as measured against the palpitations of James Brown, this is something different, and personality shouldn’t hide away at this most pivotal moment in my life as a hack critic postulating endlessly with cheap literary fiction tricks.

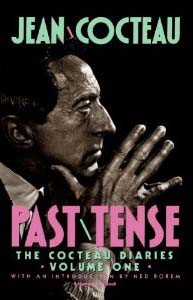

I choose the selection of books on my shelf by Jean Cocteau, but mostly just the journals Past Tense as they were the most affecting and accessible amid copies of The Imposter or Opium or The Holy Terrors—though these feature drawings by Cocteau I dog-eared and revisit frequently. I’d like to discuss the effects of his films on me or his literature as a whole and I recall in the first volume of Past Tense much of his time is taken up either with theater productions or the making of one of his films (part of the Orphic trilogy, if memory serves though it could’ve been La Villa Santo-Sospir). But really I want to focus on the merits of his journals themselves and the narrative depths achieved in a relatively simple manner but with such savvy that I’ve become convinced a part of my life might be devoted to such journaling, though I hardly measure myself as equivalent with Cocteau.

The experience reminds me of reading the notable journals of May Sarton; brief, artful things describing both the internal considerations of an artist nearing the end of his life and the actual creation of paintings, films, and theater productions—a selling point, I’d think, for anyone even moderately intrigued by Cocteau the man. His descriptions of home life, of say reading Dumas or Proust for the umpteenth time leave you breathless and in turn wanting more, wanting to reread certain things yourself and share the experiences with this elusive and vexing figurehead of art; this French devil who flew so deftly under the surface his entire life as to be acknowledged as a great visionary by known artists but in the public treated simply as a staple and artist, with little consideration given beyond that.

Perhaps the most invigorating moments within these two volumes for me are those devoted to Cocteau’s take on poetry and the process of creating verse for the poet himself. I recently printed out several translations of Cocteau’s poems (difficult to find in English) as party to an academic paper analyzing them and this accompaniment proved so fruitful that when I begin to wonder about the prospect of creating my own little treatise on the tomes incorporating a stanza or seven doesn’t seem a bad idea.

I’ll include them here, preceded by several quotes from the journals themselves related to poetry/creativity, for your immense and undying orgiastic pleasure:

“September 18 – 1951

It’s not enough to stand fast morally; one must stand fast physically.

Did the Virgin for Italy (drawing).

Yesterday saw Alexandre Alexandre [“*A journalist moving in film circles.”] for Munich.

We leave for Paris at four.”

And moving forward:

“September 28 – 1951

At my age, it’s easy. You no longer climb up the slope; enough to let yourself slide down, with all your weight. For the young, it’s not so easy: you have to climb up the slope with all your weight.”

Now to make the pivotal segue into his poetic works without batting an eye, then read said poetic passages with one eye closed because I’ve an horrendous stigmatism:

And as I (the audience member/writer/reader) become flummoxed to death by his strange meanderings from the old intellectual world and Taxi Klum Zero plays on the TV screen in front of me as I assemble notes, I find one more passage that’ll bring the work to its completion, as its quoted on the back of Past Tense Vol. 1:

There’s a yearning here that I think anyone who’s experienced that sort of marginalized acknowledgment for their efforts can appreciate. Reading these collections personifies that marginalization while giving the absolute perfect remedy for a long night that will not let you rest; and yet it isn’t due to dryness, boredom, or emptiness that these passages let the eyes finally shut, but that you find yourself reading somebody now treated as an important figure in the arts who at one time experienced that same sensation of deep insularity all the while having been acknowledged, published, produced, etc.

To discuss the relative merits of Cocteau himself strikes me as nearly impossible. His art, through the centuries, has proven to speak for itself and aside from these books I can’t find a great deal of boasting by the man related to creativity. I want him to boast, however, for after seeing his films and reading his work I understand (every single time) that there’s something at play here that transcends mere sentence structure and gets to the heart of a different take on life accompanied by romantic images and statuesque men and women coming to life and symbolism wrapped tightly in doves and madness and blood and poetry and it gives me quite the rush before I decide I’m simply an idiot trying to stand in defense of a book or series of books that those already interested should’ve purchased and read through and those slightly interested in have already Googled and are either ordering or reading the next offering to find their newest idol. Modern times is tuff.

***

Grant Maierhofer is the author of The Persistence of Crows and the weekly column A Cabana of the Mind for Delphian Inc., his unrelated work can be found at GrantMaierhofer.Org. He lives in Wisconsin and is currently at work revising a second novel for publication next fall.

Tags: cocteau

[…] Cocteau, the shelf, the lunacy @ HTMLGIANT […]

thanks. he is heroic.

thank you Joseph. yes.