Random

Death By Subtitle: How Extravagantly Fallacious Subtitles Are Ruining Books

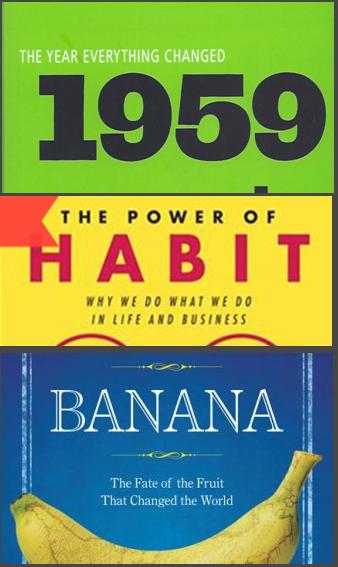

1959: The Year Everything Changed

Habit: Why We Do What We Do In Life

Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World

And now there’s Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How The World Become Modern, a book which, while very good, doesn’t live up to its subtitle. None of these books do. They can’t. Their subtitles are overly ambitious, promising that everything the reader has ever wondered about will be explicated in grand, enriching, yet academic detail over the course of the next 300 pages. Except this doesn’t happen and reader disappointment ensues. These books are all overpowered by their subtitles.

Greenblatt’s The Swerve is the history of a Latin poem, On the Nature of Things by Lucretius, which was lost ages ago and found in 1417. While Greenblatt’s love for this poem is clear and while he extols its greatness, he never comes close to explaining how the world becomes modern.

There are a few half-hearted attempts to justify the subtitle and a Malcolm Gladwell-esque idea that in history there are swerves, moments where everything suddenly shifts. (The key to having a Macolm Gladwell-esque idea involves capitalizing a noun then making it seem extremely important; luckily, Greenblatt has the dignity to avoid random noun capitalization.) Really, though, this book is the wonderfully well-researched history of Lucretius’s poem. It doesn’t have a lot to do with the entire world or momentous modernity. But if you’ve been keeping up with publishing trends, you probably already knew that.

There’s a tendency in publishing today to affix grandiose subtitles to every non-fiction book that exists. The formula goes a little something like this:

“Cool Phrase [colon] Promise that book will A.) Change Your Life, B.) Show How America Changed, or C.) Explain Everything.”

Here are some more examples:

The Devil in the White City: A Saga of Magic and Murder at the Fair that Changed America (2004)

The Eighty-Dollar Champion: Snowman, the Horse That Inspired a Nation (2012)

Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Learn (2012)

Subtitle grandiosity is a relatively new thing, meant to make books obvious so they can be easily pitched and marketed. There’s a logic to it. Theoretically, subtitles should make it easier for readers to select books. Instead of having to skim an article or book jacket flap, all we have to do is read the subtitle. Supposedly, then, we’ll know what the book is about. However, these subtitles are ridiculously misleading. For instance, Greenblatt’s book isn’t about the entire world. It’s about a single poem. The subtitle misrepresents the book.

The same way snazzy online article titles often don’t describe the articles they’re attached to, book subtitles don’t actually tell you anything about the book. They’re attention grabbers, nothing more. These subtitles are like annoying, dweeby, failed superheroes who wave their arms and scream at us, “Look at me, please! I can do anything you want! Please pay attention over here!”

And even when they’re not extravagantly fallacious, these grandiose subtitles become pompous after analyzing great book titles from the past.

Did Rachel Carson need a subtitle so it’d be easier for readers to understand her? Should George Orwell have tossed a couple of colons into the titles of his works? Would subtitles typical of today have improved these fine writers’ books or made them worse? Let’s take a look by using the subtitle formula on some non-fiction classics.

Silent Spring: How Humans Are Killing Mother Nature And Why It’s Too Late To Stop It

Homage to Catalonia: Life, Love, Death, and Politics During the Spanish Civil War, Which Changed The World

This Boy’s Life: The Inspiring Memoir About Growing Up and Overcoming an Abusive Childhood in the Down-and-Out Northwest

Alfred Kazin’s Journals: The Thoughts and Feelings of a Man Who Understood America Better than Anyone Else Ever

So honestly?

All those books sound bad.

Titles affect how we read and enjoy books. They’re the first words we encounter, even before the author’s note, introduction, or prologue. And if we wouldn’t accept such stupidity and silliness inside books, if reviewers would chastise Greenblatt for making grandiose claims in his actual text, why is it okay to do so on the dust jacket?

An anecdote: A poet once said that the final poem for a book of poetry was the title. This is because titles are part of books’ overall aesthetics. They should provide a sense of unity and honor the actual text. Authors and agents have an obligation to produce the best books possible and having such moronic and misleading subtitles hurts books in the long run. The false promises, pomposity, and silliness of these subtitles erode the reader’s trust and are insulting, as though we’ll only buy books about How America Changed Forever or How Our Lives Will Never Be the Same Again. Intelligent, enjoyable works like Greenblatt’s The Swerve and Kaplan’s 1959 get turned into bloviations, marketed to us using the same claims as self-help books and other charlatan prose.

While this ridiculous subtitling is usually a decision made by editors and marketers who simply want to increase sales—The Swerve, which spent weeks on the NYT bestseller list, is doing pretty good for a book that’s the history of a Latin poem—there needs to be some accountability. There needs to somebody at the publishing houses who’s got a modicum of modesty and after reading the book says, “Maybe this subtitle is a bit BS, even for us.”

Hopefully in the non-fiction mentioned above, the subtitles were tacked on at the end, once the books had been already written. However, there is the worry that, in this subtitle-crazy culture, authors will now write with grandiose subtitles in mind. They’ll feel obligated by commercial pressures to write books about Changing Your Life and about America! and about the History of the Entire World from Neanderthals to Jesus to George Jetson.

Instead of writing a quiet, moving study of a man and museum like Lawrence Weschler did in Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonders or instead of providing incisive insights into the legal system like Janet Malcolm did with The Crime of Sheila McGough, authors will feel pressured to write books that explain America, your life, the world, and everything that’s ever happened.

The long-term worry is that talented writers will alter their subject matter and approach, forcing themselves to make silly claims and absurd overstatements as part of an attempt to make their books more saleable. Research will be jerryrigged to lead to some tedious and unnecessary grand conclusions. Lots of nouns will become capitalized. It will be the Malcolm Gladwell-ing of American non-fiction.

So while the occasional subtitle can be fun and helpful, the subtitle glut we’re experiencing now is bad for books. And this isn’t even getting into the super-long subtitles, like Moby Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them, or the fact that now lots of novels have silly subtitle-ish qualifiers, so there’s Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War and Two Women: A Novel of Friendship.

While it’s fun to imagine parodies (In Cold Blood: A Really Violent Incident Involving Shotguns and a Nice Family Who All Got Got, Which Happened in the Back Country Some Time Ago and the Following Story Was Later Turned Into a Biopic Centered Around the Idea That One of the Killers Sort of Fell in Love with the Author, Who Ended Up Becoming an Immodest Pill Swallower and Famously Wrote, “I’m an alcoholic. I’m a drug addict. I’m homosexual. I’m a genius,” Thus Changing America Forever), it’s all a lot to take. So for the next couple months-ish let’s give ourselves a break and declare a moratorium on subtitles, alright?

***

Alex Kalamaroff is 25 years old. He lives in Cambridge and works for Boston Public Schools.

fed up and probably gonna take it anymore: tl;dr, HTML giant, and the rise of 0 comment blog culture

hahaha — [alternate tl;dr] witness the subtitle of the TL article you DR

{I shouldn’t post this so soon… or at all… aw, what the heck.}

i wish the above jpeg was a single book.

ZZZZIPP LIKES THE ‘MOBY DUCK’ SUBTITLE MORE THAN THE ACTUAL TITLE AND BETTER THAN THE OTHERS ANYWAY

DO REALLY GOOD BOOKS RETAIN SUBTITLES

LIKE GULLIVER’S TRAVELS OR LIKE ROBINSON CRUSOE OR WHATEVER OR LIKE TRISTRAM SHANDY

MAYBE ALL THESE TITLES ARE A SIGN THAT THE BOOK INDUSTRY IS HYPER COMPETITIVE DID YOU THINK OF THAT

I am currently reading Moby-Duck for a nonfiction class at my college. The author Donovan Hohn is coming to my college next week to give a “reading/convocation.” I was recently asked by some of my professors to hang promotional posters for the event all around campus. The book’s subtitle is so long that, on the posters, it has been abbreviated to The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea. To me, the rest of it doesn’t even seem necessary. In fact, the entire subtitle itself is just unnecessary, as most subtitles are.

Great post. The basic idea here–preciousness– could also apply to many fiction titles today. Instead of a quiet or simple title like “Winesburg, Ohio” ” or “Lost in The City,” you get these ridiculously overwrought titles that often begin with “What/How/Why/Where/We + verb, Because, In + insert place”, etc, followed by either lengthy declaratives or overwrought details that try to hard to establish the book’s profundity.

tinyurl.com/8rezfs7

3