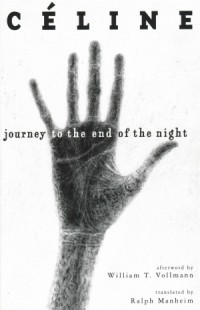

Journey to the End of the Night

Journey to the End of the Night

by Louis-Ferdinand Céline

New Directions, 2006

464 pages / $17.95 buy from New Directions

1. Will Self compared Joyce’s life before Ulysses to Céline’s experience in the war before writing Journey, in his exquisite discussion of the book upon some anniversary publication in The New York Times. I think I read that review about halfway through the novel and it complimented the thing quite well, gave a necessary contemporary slant on the whole thing.

2. Though remembered—much like Knut Hamsun—for his anti-Semitism (later in life) before his talents as an author after so many years gone by, a return to Céline and this novel in particular has occurred among authors and intellectuals almost every decade since its publication in 1932.

3. A new sort of manic transcription of the author’s experiences through his protagonist Ferdinand Bardamu jettisons the reader from war-torn France into the jungles of colonial Africa (my absolute favorite portion of any picaresque I’ve ever read) to post WWI America and back to France without missing a beat and yet the effect is akin to a hammer pounding against your chest.

4. I’ve read the book on three occasions, the last of which I suppose I felt ready enough and barreled through it in a couple of days and felt the aforementioned chest pounding that I’ve never experienced reading another book.

5. Its second translator, Ralph Manheim, also translated Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

6. Every time I remember that this is Céline’s first novel a little part of me that used to believe in writing as a career dies, then runs itself over in some hellish ghost tank, and dies again.

7. Famous for his use of three dots (“…”) in the sprawling paragraphs of his books, Céline—to me—has created a new and perfectly original way of de-Salinger-izing your first bildungsroman and turning it into a strange fucked up masterpiece.

8. Here we have the antihero, and the antihero’s doppelganger (in so many words) Robinson, who comes out of nowhere after any number of times to keep the protagonist company while he evades work, wanders around like a lunatic, and speculates about the desperate stupidity of mankind.

9. Bardamu’s a fan of kids, however; this being one of the few hopeful characteristics of the man. He believes in them, the promise of a good future, that maybe—just maybe—they won’t wind up shit like every adult he sees around.

10. The simplest characterization of this book is to say that it’s a picaresque, which is valid, but feels like the largest slight inflicted upon a great work of literature since everyone said all that shit that one time about your favorite whoever the hell; so I don’t want to do that. I want to call it a bible for people with less-than-hope but more-than-pettiness who hope to suck the congealed blood from the wounds of a better life forgone in the name of money, or democracy, or the nuclear family; and those who read it needing that companionship, needing that sense that all is not lost just yet, you’ll find it here.

11. The first time I read the book as quickly as I now feel it should be read (several days, give or take) I quickly followed it up with Exley’s trilogy and essentially had everything I believed about literature shoved through a meat grinder until on the other side there lay sprawling bloodied puzzle pieces that I’ve been putting back together ever since.

12. Bukowski liked him, which feels like a major deterrent. I guess I kind of resent the Bukowski phase I had when I was a teenager but remembering that he turned me on to Fante and Céline helps a great deal. Still though, I hate thinking about Bukowski when I read this fucking guy.

13. Bardamu makes appearances in other Céline novels, perhaps most importantly in two follow-ups to Journey called Death on the Installment Plan (basically, if you like this book, and want to spend a few hundred more pages with its creator, you’ll enjoy Death, you may find yourself laughing harder as well and breezing through pages easier than with Journey but the merit still resides with his first book, in my opinion) and Guignol’s Band, a much shorter book than the first two that brings things to a nice level of completion by packing every inherent punch Céline mastered while deftly discussing his distaste with the reception of his previous works.

14. I once read somewhere about a man reading this book on a single train ride and disembarking the train feeling nauseous and like his life had essentially been shoved inside a blender (I’m paraphrasing) and perhaps because of this the last time I read it I finished pacing around under those heated lights at a Chicago El station.

15. ALSO! I always make a point of listening to “End of the Night,” by The Doors a shitload when I’m reading this book because apparently Jim Morrison was a huge fan and having that context to listen to one of their lesser-loved ballads really does the fucking trick.

16. Most of the pictures of Céline towards the end involve him and cats; which brings up any number of questions relating to the intellectual and cats (Hemingway, Cortazar, this fucking guy) but I don’t have a cat so it never goes beyond the bringing up of the questions.

17. The passages depicting Bardamu as a doctor working in a shitty-ass Paris suburb really make my skin fucking crawl. I suspect there’s an attempt at much of this book making the general public’s skin fucking crawl but for me this is really the only time it happens. All we’ve heard about Paris during this time and Henry Miller and the clap and tuberculosis and these cramped apartments and this miserable bastard attempting to heal people but not really giving a shit. Very fucking irksome.

18. The closest contemporary comparison I care to think about is with the Gaspar Noe film I Stand Alone wherein an older French man spends much of the time walking around talking to himself about everyone around him being a bunch of cowards and assholes and although Bardamu leaves France for a great deal of the book I still fondly recall one when watching/reading the other and vise versa and it makes for a solid moment or two.

19. As I understand it, some asshole made a film using this as the title and maybe there’s some correlation but still that seems pretty fucking bogus.

20. Also, according to Wikipedia, some group called AntiBoredom invented a game using the novel’s title wherein a group of people races wearing ribbons trying to tag each other and shit. I like this more than the idea of a filmmaker using the title, but that’s really all I care to say about the matter.

21. THIS IS INTERESTING! The Mekons have an album using the book’s title! Jonathan Franzen loves The Mekons and made this really fucking stupid promotional video for them saying “they’re the band for you!” so this is totally preferable to Bukowski talking about Céline. Jesus. Fuck. I’m never going to listen to The Mekons or see that film or play that weird game. People are weird. People suck. Nope. Never mind.

22. William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg visited Céline toward the end of his life and apparently he was a muttering asshole which seems about right and who the hell cares?

23. Every single time I read this novel I reread this passage over any other around 24 times. It’s right about when Bardamu is coming out into the streets of New York and it blows my mind.

Raising my eyes to the ramparts, I felt a kind of reverse vertigo, because there were really too many windows and so much alike whichever way you looked that it turned my stomach.

Flimsily clad, chilled to the bone, I made for the darkest crevice I could find in that giant façade, hoping that the people would hardly notice me in their midst. My embarrassment was quite superfluous. I had nothing to fear. In the street I had chose, really the narrowest of all, no wider than a good-sized brook in our part of the world and extraordinarily dirty, damp and dark at the bottom, there were so many other people, big and little, thin and fat, that they carried me along with them like a shadow.

24. If you’re going to write a book about your own experiences your focus needs either to be on compiling a wild-enough slew of experiences or cultivating an interesting-enough writing style to carry you through taking another shit or going on a date you don’t-like-so-much, and here Céline has masterfully accomplished both in a way that will likely be remembered for 10,000 years.

25. For a brief time reading this book I feel consumed with such a deeply-rooted love for Céline or the prose or the story or whatever the fuck that everything else (literature) suddenly strikes me as offensive. I hate the fact that I ever once read and loved Mailer, for all I care to do is dig deeper and ever deeper into this goddamn lunacy, and then I finish, falling asleep.

Tags: 25 Points, Journey to the End of the Night, Louis-Ferdinand Celine, New Directions

[…] 4. I’ve read the book on three occasions, the last of which I suppose I felt ready enough and barreled through it in a couple of days and felt the aforementioned chest pounding that I’ve never experienced reading another book.” Read the rest HERE. […]

On Celine’s anti-semitism and the unpublished “manuscripts” (sic): http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/jan/14/uncovering-celine/

Thanks for posting this, very interesting. I tend to ignore most anything that happened much after Death on Credit/the Installment Plan because of this shit, but every now and again I feel like that’s a grotesque denial of what a psychopath Celine was, so I’ll read up and get disgusted. He wrote some phenomenal books, and gave new depth to misanthropy, etc., but all the same, what the fuck. Then I remember every diversion in Reader’s Block listing the vast array of anti-semites as far back as Voltaire and realize there was fucked political/cultural thinking in most of the world’s best loved authors.