Until recently, there was only one memoir, that isn’t even a memoir, I truly loved—an essay by Cheryl Strayed called The Love of My Life which originally appeared in The Sun. I read that essay often because it is unbearably intimate, the writing is impeccable, and the essay, the memoir, the writing speaks to something greater than the story being told.

I don’t read a lot of memoir which is kind of strange because I am nosy. I love reading personal blogs and I’m fairly obsessed with reality TV where I can witness unbearably intimate moments in people’s lives even if they (and I) are fully aware the subjects are choosing which intimate moments to expose. Memoir is much the same way. Like reality TV, a memoir doesn’t provide the reader with unfettered access to a writer’s life. That access is measured; it is controlled. We may learn private, intimate things about someone’s life but only because they want us to know those things. There’s a deceptive quality to the honesty of memoir.

Even though I find similarities between memoirs and one of my favorite indulgences, I have long stayed away from reading memoirs because I haven’t quite understood what compels people to divulge their secrets. It’s one thing to dress the truth up as fiction, but to share the truth as truth is another matter entirely, one that confounds me.

I have no idea how to review a memoir because you’re not only reviewing the writing or how someone conveys their recollections of some aspect of their life, you’re also, in some ways reviewing the life lived. That makes me uncomfortable. Who am I to judge? Who am I to traipse through a writer’s memories. They’ve chosen to expose themselves, yes, but have they chosen to have that exposure dissected?

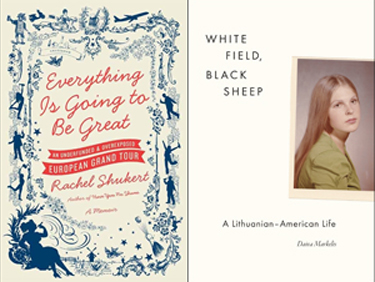

I first learned of Rachel Shukert when I read an excerpt of her new memoir Everything is Going to Be Great on Salon. The excerpt itself was interesting enough that I wanted to read the entire book. I consulted Dr. Google and learned she has written two memoirs and is close to my age and I thought, “How curious.” I am always fascinated by young memoirists. What could they possibly have to write about? I received a copy of Shukert’s book, quickly read it and for the most part, I really enjoyed it. That was more than a month ago and since then I’ve struggled with figuring out how to write about the book and how to write about memoir.

Around the same time I read Everything Is Going to Be Great, I also read another memoir, White Field, Black Sheep: A Lithuanian Life by Daiva Markelis. I was somewhat hesitant to read Daiva’s memoir because she is also a new colleague at my new job (yes, yes, I’m talking about someone I know; tar and feather me). If I didn’t like the book, I didn’t know her well enough to know what to say. Also, sometimes when someone says, “I’ve written a memoir,” the story doesn’t end well. If I didn’t like the book, it would make things awkward. This story, fortunately does end well. White Field, Black Sheep is a very different book by a very different woman but one I also enjoyed, one that moved me inexplicably and, at times, to tears.

I was thinking and writing about memoir the other day and I said it’s not that I don’t trust my own memories but rather that I don’t trust others with my memories. As I’ve thought about how to write about these two memoirs, I’ve thought about how memoir writers have to trust their readers with their memories. That’s a big thing to me. I imagine it requires a great deal of courage for anyone to write a memoir, to say this is my life without knowing how readers will respond.

I have a good memory but I don’t. I can tell you that for the most part I had a happy childhood. I remember certain incidents like the time when my youngest brother, then a baby, grabbed the ice cream off the cone my middle brother was holding and shoved that cold ball of vanilla into his mouth and laughed his baby ass off. Years later, there would be revenge and I remember that too. I can look at certain pictures and feel a vague sense I have been in a given place before. Beyond that, though, I do not have precise recollections of many moments in my life. I did not keep a diary. I can’t tell you about what happened in the fourth grade. Another reason I have avoided memoirs, I think, is because I don’t understand how memoirist are able to remember so much of their lives with such clarity and then are able to talk about their lives with such poignancy. I envy that ability.

When James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces was revealed to be fiction, I wasn’t outraged. I didn’t waste any energy on the matter. I didn’t care. He lied or was made to lie. Whatever. Writers lie and some of us are better at lying than others. At the same time, there must have been an impact for memoirists who came after Frey—in the wake of his mendacity all the memories of memoirists would surely be interrogated as fruit from the poisoned tree. As I read both of these books, I never gave a thought to the veracity of the writing. The more I read, the more I realized the truth of the stories being told is not the point.

Everything Is Going to Be Great is a memoir of Shukert’s adventures in Europe after graduating from college. At first glance, the most notable aspect of the memoir is the self-deprecating humor with which Shukert recalls a series of truly dismal experiences across the great continent—an unpaid role in an experimental play, constant brushes with poverty, a dental crisis without health insurance or much money in a foreign country, ill-advised affairs with inappropriate men, and visiting Austria without being able to escape the country’s Nazi past. The levity is tempered with moments of gravity and Shukert negotiates that balance quite well. The way she expressed her anxieties while in Austria was very affecting and by the end of the book, I had a real respect for her self awareness.

One of the finest moments of self-awareness is when Shukert writes, “My escapades never really felt real until I had told someone about them. I needed other people to prove to myself that I existed.” She goes on to note she knows her attitude isn’t healthy but I suspect most of us have felt that way, have felt that to exist, we must expose. By the measure of this memoir, Rachel Shukert exists quite vividly.

In addition to the misadventures, most of them drunken and sex-fueled, Everything Is Going to Be Great is a memoir about a young woman finding herself without being so trite as to be a memoir about a young woman finding herself. The more of the memoir I read, the more I wanted to know what happened next and because I love a happy ending, the more I wanted to have some kind of reassurance that everything ended up being great. There was a real tension as the story, such as it were, unfolded and there came a point, in Amsterdam, where Shukert is engaged in an adulterous affair with a man she thinks she loves enough to will his real relationship away. I thought this is how we come to the end, but it wasn’t. After the denouement of that relationship, there was more to the story, a happy ending where Shukert met a nice Jewish boy in Amsterdam and brought him back to New York with her and I felt a real satisfaction to know that there had been a purpose for the purgatory.

One of the least discussed aspects of this book is how it revealed, only as great writing can, the complex relationships between mothers and daughters. The most compelling parts of Everything Is Going to Be Great were not the awkward sexual encounters or the self-conscious accounting of debauchery. The most compelling moments were exchanged between a mother in Nebraska doing her best to love a complicated daughter tormenting herself across Europe. For me, the story of Shukert and her mother, was the true heart of this memoir. Toward the end of the book, Shukert’s parents are visiting her in Amsterdam. They go out to dinner with her boyfriend Pete, the man with a real girlfriend and after Pete assures her mother he loves Rachel, there is a moment when Shukert is looking at her mother. She writes, “Slowly, I raised my eyes toward hers expecting to see a bemused gleam of triumph. There was none. She looked like she was about to cry.” It’s a very subtle moment, but one that perfectly captured the depth of the relationship between mother and daughter. Given the decadence of so much of the book, these subtle, stripped down emotional moments made the memoir far more nuanced and elegant than I first realized.

The only part of Everything Is Going to Be Great I did not care for was a series of tongue in cheek interludes—humorous tips about various aspects of life as an ex-pat in Europe. The interludes felt a bit indulgent and overly performative and I started to get frustrated when I came upon them because I wanted to stay immersed in the story. I eventually stopped reading them so I wouldn’t get mad. These interludes detracted from really engaging, passionate writing about those awkward years after college when most of us have no idea what the hell we’re doing and how fortunately, we can, with a little luck, survive those years. That’s why I ended up loving Shukert’s memoir–because like the Strayed essay I mentioned at the beginning of this post, it aspired to something beyond itself. The Strayed essay was painfully revealing but it was also graceful and spoke to love, betrayal and grief in ways I could relate to. Shukert’s memoir on the surface seems like a humorous accounting of a European adventure gone awry but to say that’s all the book is about would be to do it a disservice. In reading about her experiences, I was able to recognize parts of myself. I was able to feel something. I don’t know a lot about memoirs but I am starting to believe that the best memoirs not only allow the writer to share some part of themselves, they allow the reader to share some part of themselves too.

So often, writing is a love letter. White Field, Black Sheep is a love letter to a mother and father and to a life lived or as the second half of the title book says, a Lithuanian-American life lived. White Field, Black Sheep details Daiva Markelis’s childhood growing up in a Lithuanian neighborhood, as the daughter of Lithuanian immigrants in Cicero, Illinois. This memoir affected me far more profoundly than I could have ever imagined because I too am the child of immigrants. Nearly every experience Markelis shares is one I too have experienced—parents speaking to you in their native language in public and butchering English, often willfully, speaking one language at home and another at school, a complete disavowal of processed foods, a cross country vacation to better appreciate America, watching parents try to hold on to the past while reaching for the future. The immigrant story is often the same story no matter where the homeland. Once again, I was able to read about someone else’s life and find myself.

The memoir has a really interesting cadence and structure to it. Stories from past and present are merged into a circular narrative without a beginning or end. In the early chapters, much of the tone is nostalgic and truthfully it took me a while to feel invested or engaged. The writing was good but I didn’t feel.That early writing evokes a sense of time and place as Markelis details the landmarks of her childhood, the world as she would understand it for many years. There is an almost idyllic quality to how Markelis describes much of her childhood but a sly humor emerges. Markelis’s dry observations made me laugh even during moments when laughter felt inappropriate. One such moment is at her mother’s funeral where a childhood friend, Arvid, now a priest, will lead the service. “My fear is that Arvid will monpolize the time with yet another episode of the Father Arvid Show, that he will recreate the neighborhood of our youth, painting detailed portraits of what it was like living next to the Markelis family before finally getting to the virtues of my mother. But his eulogy is fairly short, at least in Arvid Time.”

I appreciated the way Markelis shared a moment from her childhood then drew a map to a moment in her life as an adult. At one point, she talks about her first husband’s love of cooking and how he said her mother never taught her anything because she didn’t cook as well as he wanted. She writes:

“This is not, strictly speaking, true. My mother taught me how to make birds, graceful cranes, from little pieces of paper. She taught me how to recite form memory, with perfect Lithuanian precision, all twelve verses of the children’s classic Meskukas Rudnosiukas when I was only three. She taught me to avoid heavy, sweet smelling cologne— “You don’t want people fainting all around you”—and to stand up straight because, “Tall women have more fun.”

Such maps, if you will, are woven throughout the narrative. They are subtle but they reveal so much about a failed marriage, a deep bond with a mother, and the memories children hold on to and are shaped by. More than once I thought, “this is so very graceful.” It is impressive how much of a life Markelis manages to write into her memoir without explicitly writing the whole of her life into her memoir.

Given that I know Daiva, there were times when I felt privy to secrets to which I had no right. In the latter half of the book, Markelis discusses her alcoholism as well as her father’s. This is not the main focus, but in reading about these experiences the unbearable intimacy of memoir became almost too unbearable. It’s one thing to want to know about the lives of strangers, but do we want to know, truly know, the people we know?

I don’t know where the boundaries of memoir begin and end. We can write about ourselves but do we have the right to write about the people in our lives? Markelis is frank, funny and downright charming throughout the memoir and seemingly fearless in what she shares. And yet, there were curious omissions. For example, we don’t know much about her sister nor do we learn much about her first husband. We are left to imagine the histories she shares with these people because although she exposes a great deal of herself, there are some things, she has chosen not to expose. Access is measured; it is controlled.

It is the end of the memoir where the writing became something greater than itself— dense and poetic and surprisingly moving. In the last chapters, I found the greatness I was looking for in the early going and it was so unexpected, I nearly dropped the book as I read. Starting with the chapter, The Alphabet of Silence, the writing soars. I hate to use that phrase but I cannot think of a better way to describe the shift in tone and the heights reached by the prose. Ii’s almost as if it’s a completely different memoir, one even more revealing and honest than the one preceding it. There is a wisdom to the writing as Markelis writes of her father and his unfinished dreams and the ways in which she got to know him as he corresponded with her while she lived abroad, and later, through an essay he himself wrote about his own father. She writes of her mother, dying from cancer and juxtaposes making arrangements at the funeral home and deciding whether or not her mother should wear underwear in her coffin with a beautiful last line, “I will see my mother in the brittle shadows of winter birds.” Before that though, Markelis details her mother’s last week. The revelations are unbearable and they are intimate but these revelations also taught me why we read memoir.

Tags: Amsterdam, Chicago, Daiva Markelis, memoir, Rachel Shukert

Really lovely review, Roxane. You made me want to go buy Ms. Markelis’s book– that last line is a knockout.

Cheryl’s essay is one of the most moving pieces of nonfiction I’ve read (I know her through an acquaintance– what a kind and generous writer, with her time, and in her vision).

Excellent reviews, Roxane. At their close, I had goosebumps.

The Book of Embraces, by Eduardo Galeano, is a splendid rose window of memoir. If a person is the buoyed-apparent part of a familyberg, then the excellent Running in the Family, by Michael Ondaatje, is an excellent memoir.

[In the blocked quote from Markelis, how to recite from memory?]

Ms. Gay,

I am a memoirist. Not only did your article make me want to read the memoirs you wrote about; but it made me appreciate more what I choose to write and why I choose to write it. You have picked up on the subtle nuances of memoir. When you wrote of feeling satisfaction that there was “a purpose for the purgatory,” I realized that for me anyway, that is part of the purpose of writing memoir – to discover the purpose for the purgatory. That line will give me a goal to reach for in satisfying my readers.

[…] 3)Rachel Shukert! Reviewed here. […]

It takeddd

It takes real courage to write memoir. It is a made up truth–in that it’s an account of a subjective experience–but it’s a made up truth that the author has to stand behind and say, “Yes, this is what I did. This is how I handled this event in my life.” Some people do get turned off by this sort of honesty, but I have found some of the best, most important and effecting work I’ve ever read was memoir.

Also — this web form is gving me fits!

And thanks for the reminder to put White Field, Black Sheep and Ms Shukert’s work on my Amazon wish list so Santa knows what to bring me.