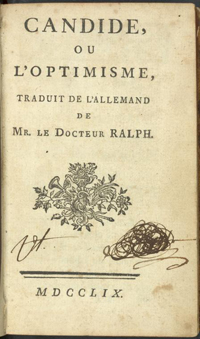

Candide

Candide

by Voltaire

Norton Critical Edition, 1991 / 224 pages Buy from Amazon ($11.56)

Penguin Classics, 1950 / 144 pages Buy from Amazon ($11)

I must have had g-rated goggles on when I first read Voltaire’s Candide because I didn’t remember how violently twisted the book got. Published as satire in 1759, it attacked Leibniz’s idea from his Monadology that this world was the best of all possible worlds. History intertwines with fiction in Candide as the backdrop of the Seven Years’ War and a deadly earthquake in Lisbon that killed more than fifty thousand people fueled Voltaire’s rage. The religious men of his age, the ‘optimists,’ tried to comfort people with the idea that everything, no matter how vile, happened for a greater good as it was driven by a higher power. Dr. Pangloss, Candide’s tutor and an obvious caricature of Leibniz, espouses this belief and Candide carries forward it as a conviction throughout much of the narrative. Voltaire drills in his rebuttal with the violent imagery of something straight out of a Takashi Miike film.

Take for example, Cunegonde, the love of Candide’s life, as she shares her tragic story:

As horrific as this sounds, shortly afterward, they meet an old woman who assures them her misfortunes outweigh theirs. She used to be a princess until her betrothed was poisoned through chocolate. She was then carried off as a slave:

Candide and Cunegonde are separated when they arrive in Buenos Ayres[sic], and the remainder of the novel is Candide’s attempt to rescue Cunegonde so they can marry and live happily ever after. If a reader picked up the book without knowing this was all a satirical effort, they might be horrified and mistake the detached tone of the narrative as some kind of depraved scientist or researcher noting the sufferings of humanity in bullet points.

Candide seems the work of a younger man filled with angst and rage against the evils of the world. But it was actually written in the second half of Voltaire’s life. Voltaire couldn’t even take credit for Candide when it was initially published for fear of imprisonment. He’d already been censured and arrested several times, having to endure harsh punishment for his writings. Every word had to count, which might in part explain the brevity with which so much information was packed in.

A closer examination of the text reveals the discipline of a detached commentator who lets the material speak for itself. Ever present is the ironic stance of a man who wants to give up, but can’t, clinging to the world he despairs of while mocking it. The closest Voltaire ever gets to offering an alternative is in his description of Eldorado, the legendary city of gold which Candide accidentally stumbles upon. There’s innumerable wealth, people are at peace, everyone treats each other with respect, and gold and diamonds are considered as worthless stones. Eldorado is literally the best of all possible worlds. But Candide isn’t satisfied:

Even if provided something like Heaven, man would abandon it in pursuit of his own glory. When Candide finally achieves his goal of consummating with Cunegonde many years later, he discovers his wife has lost all her beauty as she:

His only solace is farming and tilling the land, in line with man’s original Biblical purpose. Is this a facetious ending, or one which has a glimmer of sincerity? Does Voltaire really believe man can only be happy when he goes back to his role as caretaker of the garden, or is this ending just as tongue-in-cheek as the proclamations of Pangloss? Even at the end, after Pangloss miraculously comes back to life (there are plenty of these unrealistic twists and turns), Candide asks:

‘Now, my dear Pangloss… Tell me this. When you had been hanged, dissected, and beaten unmercifully, and while you were rowing at your bench, did you still think that everything in this world is for the best?’

‘I still hold my original views,’ replied Pangloss, ‘for I am still a philosopher. It would not be proper for me to recant, especially as Leibnitz cannot be wrong; and besides, the pre-established harmony, together with the plenum and the materia subtilis, is the most beautiful thing in the world.’

Subtlety isn’t a trademark of the book and its mockery of the bildungsroman leads it to ridiculous heights. But would Candide be as effective if one took it on its own, divested of its commentary on Leibniz and optimism? Is the literary merit of Candide the strength of Voltaire’s argument, or the strength of the tale described within its pages?

Putting aside the fact that Leibniz’s philosophy is more complicated than the way it is presented within the book, Voltaire succeeds in showing us that his was a pretty horrible world. Life was rough, disease and war were rampant, law and order were frequently absent. Leibniz’s opinion, along with that optimistic view of religion, gets demolished. Optimism doesn’t stand a chance. But on that stance, it seems even the Bible would agree, as in the case of the book of Job who loses everything in horrific circumstances (children and servants are killed, he loses his wealth, even his body becomes afflicted). His friends arrive and take on the role of the Optimists and they engage in poetic diatribes to prove there is a reason behind everything. Job takes on the role of Voltaire, defying the explanations made by his friends. At the end of the book, it’s the friends who are chastised by God, not Job.

If a reader divested the book of its religious commentary, Candide unfortunately gets lost in a bit of a repetitious cycle. The wanton destruction becomes more and more absurd, absolutely no one is happy, life is miserable. Voltaire’s point is made sufficient within the first ten chapters. As for Candide as a hero, he has two noticeable traits; his unwavering faith and his ability to kill people. But he’s not even faithful to Cunegonde, sleeping with the Marchioness at one point.

Where the book really succeeds are Voltaire’s ‘candid’ descriptions of his period, however exaggerated. They are caustically witty, as are his insights into human behavior. This is no light-hearted read, and his criticisms extend far beyond Leibniz to the Pope, governments, and even the arts. Nothing is off limits for Voltaire and a dark sense of humor pervades throughout. The unmatched flair for destruction also draws readers in with their wanton desire for seeing yet another wreck. Even the side characters, who reflect the extreme one-dimensionality of satirical symbols, drip in outrageous irony. Take the sailor who causes the death of a noble Anabaptist, then finds some money to get drunk after landing at the port:

A murderer not only gets away with his crime, but he sleeps with a prostitute afterwards. That sort of attention to lurid detail is what gives Candide its strange appeal, as is Voltaire’s condemnation of the behavior by rewarding it. And while it’s not as successful in transcending the message it is railing against, say in the manner of the Chinese classic, Journey to the West (Journey to the West criticized Taoism, as well as many other aspects of Chinese society, and still became known for its own literary merits), it’s still a fascinating glimpse into a carnival of all too real behavior. Bound back up with the argument it is clashing with, Candide becomes an even more hilariously disturbing romp that challenged the notions of the time and posited harsh truths the readers knew all too well but could not openly countenance. Optimism met its match in Voltaire, and ironically, both are indebted to each other for their continued survival. Almost three centuries later, we’re still enjoying the fruits of that battle.

***

Peter Tieryas Liu has a collection of short stories, Watering Heaven, coming out form Signal 8 Press in the fall of 2012. You can follow his writings at http://www.tieryasxu.com/watering-heaven/

Tags: Candide, Peter Tieryas Liu, Voltaire

[…] Check it out here! […]