Your Attraction to Sharp Machines

Your Attraction to Sharp Machines

by Matthew Mahaney

BatCat Press, May 2013

53 pages / $20 Buy from BatCat Press

A woman from the audience asks: ‘Why are there so few women on this panel? Why are there so few women in this whole week’s program? Why were there so few women among the Beat writers?’ and [Gregory] Corso, suddenly utterly serious, leans forward and says: “There were women, they were there, I knew them, their families put them in institutions, they were given electric shock. In the ’50s if you were male you could be a rebel, but if you were female your families had you locked up. There were cases, I knew them, someday someone will write about them.”

—from Stephen Scobie’s account of the Naropa Institute tribute to Allen Ginsberg, July 1994

“her exhalation

tion”

—Jon Woodward, “Huge Dragonflies,” Uncanny Valley

The back of Matthew Mahaney’s book, Your Attraction to Sharp Machines (AMAZINGLY assembled by hands at BatCat Press) is a silver and black Rorschach image (unique to this copy, #48 of 75) spread across a burlap-ish fabric. I stare and decide it looks like an insect head coming towards me. I think of what it means that this is the shape I chose to chisel the blob into, that this is what this mutable part emerging from the ether is to me. A PhD student is sharing the severely air conditioned portion of the TA office with me. He squints at it, moving around his glasses for a second, and says, “Isn’t it duck feet?” I look at it again and shrug.

E.T.A. Hoffman’s famous short story, “The Sandman,” is built mostly by letters sent between disoriented characters. The letters all dizzily revolve around the horror of attempting to see WHAT and WHO thrives on not being seen or perceived beyond a modestly eerie feeling that “something is off” (the Bogey-men / the Sandman / cyborgs / automatons). Nathaniel, the main character, can’t address his correspondence to the right person, he can’t understand (through his telescope) that he’s entertaining cheating on his fiancee, Clara, with a doll1 (untouchably named Olimpia), and he is haunted by either a man or a male figure of his imagination (the Sandman), who may be stealing the eyes of children at night and selling expensive / haunted Italian eyewear during the day. It is a story about the kickback / the recoil that occurs when there is an un-trusting of the senses / your instincts and their skill set. (“You’re only human,” someone says, to comfort you when you get it wrong.) It is a story that makes us wonder about what our criteria for a human being IS exactly (particularly when we’re talking about women). Most importantly, Hoffman’s disturbing tale questions the confidence we have our in our ability to recognize the difference between person and our most ancient illusions and our newest machines as they meet inside unfolding human events.2

Something I’m getting at is that “The Sandman” plays into a very important part of poetry (and Mahaney’s book): how quickly things can become de-familiarized and what can and does happen to a piece of consciousness when it experiences or expresses that (in the real world and in the more malleable and forgiving forestworld of the ‘poem”).

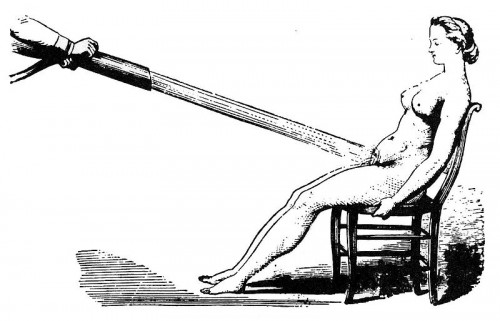

A USEFUL GRAPH // The Illustrated Uncanny Valley

Poetry knows, in deeper oceans than most forms of writing, the pain that is inevitably linked, both to seeing and to articulating what has been seen. An unnamed narrator of “The Sandman” comes out between the letters to say this on the matter:

When it becomes difficult or overwhelming to decipher and decode what and who is happening in front of you through bites of language, the consequences are mostly Innocuous with a capital I until they aren’t. (Poetry is always potentially toying with this line. Yes, there are birds in my throat. Sometimes I am amazed I do not find actual feathers in my toothbrush when I brush at night.) Towards the end of Hoffman’s story, when Nathaniel suddenly sees one of Olimpia’s eyes rolling around the floor like somebody’s dropped blueberry, he starts trying to kill people until he’s dragged off to an asylum.

Nathaniel’s abandoned, but his decidedly more rational fiancee, Clara, probably goes on to become one of those Women Laughing Alone With Salad.

Serious question. Do you, reader or writer or person with an imagination prone to break its bridle and every sensitive bone in your body, wonder if you would have been placed in some kind of institution (military (if you are male), mental, marriage, sanitorium) were it not that many years ago? I really do. Have you read Kate Zambreno’s Heroines? Zambreno recounts how a number of writers’ talented and vivacious wives, girlfriends, and muses are locked up in various institutions with the same thought you’d grant a rumpled dinner napkin. Christian Hawkey’s Ventrakl? Both George Trakl and his sister, Grete, were in and out of various institutions for their mental instabilities. Trakl’s difficulties were heavily exacerbated by his WWI service and substance addiction. One of the women Gregory Corso is talking about is Elise Cowen, a close friend and ex-lover of Allen Ginsberg who was most certainly writing during the Beat era. When I right click a photo of Corso to save it, the computer lets me know that the photo has simply been named, “beatgirl.png.” I make a face. No doubt any neon smile of a weatherman would predict bad things for me in a different time and place. The last part of what Corso says (In 1994!) should distress more of us. “Someday someone will write about them.”

Elise Cowen

Mahaney’s book has the feel of wondering backwards towards a time and place (It is murky which time and place specifically. It shares something with Jesse Ball novels in that way.) when it was dangerous for women (In this case, for a woman named Elizabeth3) to discuss ideas and feelings that couldn’t co-exist with what was deemed acceptable4 for their regularly imprisoned bodies and minds to inhabit. “She failed and chewed / when I asked what she meant. / The nurse said she’d been whispering to herself. / I have no room for a second skin” (24, The Institution). Your Attraction to Sharp Machines physically (!) unfolds into three sections, which are secured in three pockets, “Pages from the Sister’s Diary,” “The Institution,” and “Letters from Jonah Bell.” Three different perspectives, A sister (a double and potentially ‘healthy’ version of Elizabeth. Note that the Uncanny Valley graph attaches the word ‘healthy’ to 100% or total familiarity.), a doctor in an asylum of a kind, and a would-be or might-be lover called Jonah Bell (the only named person besides Elizabeth in Mahaney’s book), throb against one another to create a choked picture, a chronicled knowledge of a peculiar femghost, who is still considered human, but in a way that is both repulsive and a curiosity to the majority of those who surround her.

Like Nathaniel in Hoffman’s story, Elizabeth cannot be “trusted” to tell us what she sees.

Elizabeth pulled a curve of broken glassfrom her pocket. She knelt

and dragged it through the dirt. My name

then hers. She drew a face like mine

above my name. Her hair

blocked my view

but when she stood there

was another face next to mine.

A wrong face. The wrong teeth”

(4, Pages from Sister’s Diary).

The job of seeing Elizabeth and seeing for Elizabeth falls to the ‘authorities’ Mahaney gives us. However, Mahaney is aware in a way the speakers themselves seem not to be of how removed and flawed their accounts are. Though, Elizabeth perhaps is the only one that does realize how far they are from accessing her. She takes an extra step further away from those who are caring for her by donning, here and there, an extremely tight-fitting mask (there’s mention of a beekeeping veil5 as well) of some kind. “I cannot look / her in the mask” (11, Pages from the Sister’s Diary). Letters, diaries, a medical professional’s personal notes, are all, of course, ripe and ready to be fucked by subjective feelings and desire and handwriting and protocol.

The tension of this situation is radically captured by Mahaney via the sounds of these lines being framed into poetry. I find this aspect of how the book’s poetry functions to be rather stunning considering that Elizabeth has been blinded in her eyes and in the rest of her body from the world, forced into a controlled environment where her senses can be constantly monitored and corrected. The world has been blinded to her full sensory experience of it as well. “The patient said it seemed as / though she both couldn’t and shouldn’t talk” (12, The Institution). “Dear Elizabeth, I have finally stopped trying to trace / the shape of your voice” (53, Letters from Jonah Bell). How does she reach us then but through the consistent rattling and almost violent emergence of sharply edged sound beyond the sound of words? Vibrations can penetrate a wall. I had the unnerving feeling of being consistently and beautifully chewed on, snapped into bits by the angles of these lovely rooms. “Dear Elizabeth, I sometimes think of you as a new kind / of noise…Your tone is ankle crack, / is wrung from treetops cased in week old ice. If only your metal stems could inspect my skin” (36, Letters from Jonah Bell). Elizabeth seeps out of everywhere and nowhere.

The book is also permeated with doubles or pairing, with instances in which the three voices charged with telling us about Elizabeth unravel one another, and like Hoffman’s story also became famously known for (Freud wrote an essay which heavily delves into the story called “The Uncanny”/ “Das Unheimliche”), Your Attraction to Sharp Machines is entangled with the strange and violent relationship Psychoanalysis has with ‘hysterical’ women. Both Elizabeth’s sister and her potential lover, Jonah Bell, serve as doubles. Elizabeth’s sister, who gives pages of her diary to the doctor, is uneasy with Elizabeth’s behavior and insistence on acting out. “Her sister…reports that the patient of talks of love and marriage in a bold manner, though she declined to peruse / the notes we have made regarding similar sentiments expressed / during our sessions” (23, The Institution). Though she is the opposing, more appropriate model of the feminine set against Elizabeth, she appears to be as curious about the emotions and intensity behind Elizabeth’s behavior as she is fearful of it. The only meaningful relationship she appears to have is with Elizabeth.

Eats every last one.She licks her fingers through

the hole in her mask

then bares

the back of her neck. My face

pulses. Flickers.

It feels like fire”

(8, Pages from Sister’s Diary).

Helene Cixous, who writes about doubles in her essay on Freud’s “The Uncanny”/ “Das Unheimliche,” allows a reading of the siamese coupling of these women as one which allows neither one of them to fully express or explore themselves. Cixous says,

“The double thus absorbs the unrealized eventualities of our destiny which the imagination refuses to let go. It produces, particularly in the reading, the ghostly figure of nonfulfillment and repression, and not the double as counterpart or reflection, but rather the doll that is neither dead nor alive” (540).

They are both the doll, both the de-boned ghost. “I cannot / run and I need to be able to run,” (11, Pages from Sister’s Diary) says the sister. The fact that the sister’s voice and narration again appear between the doctor’s notes in “The Institution” to further extrapolate on how Elizabeth processes and reacts to her living within the sterilized space also heavily hints at the confining of the sister whether or not she is actually locked up in the asylum with Elizabeth.

Jonah Bell, on the other hand, we have a character / narrator / double who speaks as intensely, as poetically as Elizabeth does when we hear her voice through others / the way her voice INFECTS others unbeknownst to them / absolutely beknownst to Mahaney. Bell is the only character who is as equally unafraid of strangeness and the force of awe as Elizabeth is.

“I rub myself with ice, ice and honey every night but then I’m up, wake up, and my bones are wrapped in cotton” (13, The Institution).

“Dear Elizabeth, some mornings I’m convinced I’ve remembered / all the wrong things. If dead moths keep accumulating in the windowsill, does that mean another month of buildings obscured by fog?” (52, Letters from Jonah Bell)

Bell is the most intimate with Elizabeth, writing letters that speak to her only / which replicate, as closely as any writing can, both conversation and touching. He also speaks often of meetings with her and from the sister’s voice (She is uneasy and afraid of him, just as she is Elizabeth) within the doctor’s notes, we know he visits her “every second Sunday” (26, The Institution). In the letters, Bell states that he disagrees with or is wary of the doctors assumptions of Elizabeth. “The doctors never diagnosed your / inability to swallow salt, your attraction to sharp machines” (31, Letters from Jonah Bell). “…the doctors make mistakes every other week. They write bursitis when they mean tumors, mistake depression for insomnia” (32, Letters from Jonah Bell). Bell suggests, loosely, that he has his own struggles with being healthy. “The mongrels make their muzzle sounds as the pills in my cupboard turn to little piles of powder” (48, Letters from Jonah Bell). However, the fact that he is able to visit Elizabeth in the asylum suggests that he is not confined in the way she is, despite the fact that he says, “I read your chart and found out we’re the same” (32, Letters to Jonah Bell). He may find her amazing. He may fully see the connection they share. However, Elizabeth, as an imprisoned woman positioned and doubled next to his status as a free male figure is husked, scooped out. His eyes are tender, but they are still not hers and that is a loss the reader must acknowledge.

Last of all, we have the doctor, who speaks to us as voice of the culture at large. Elizabeth speaks to the doctor in sexually explicit ways, in the ways a sexual object does. “I don’t like cleaning kitchens. I want to play the piano and get the keys all dirty” (14, The Institution). She speaks to him and she is Anna O, Dora, Zelda Fitzgerald, Joan of Arc, Elise Cowen, the madwoman in Mr. Rochester’s attic, a doll you should fear will come alive at night.

A Treatment for Hysteria or Let Me Give You This Orgasm via Firehose and Then Call You a Whore.

“Today the patient complained of the cross she has to bear. / A cross of flowers, a sweet cross even if there is a good deal of filth in / it…I don’t know / if it’s necessary tell you if I ever sat on a man’s lap” (22, The Institution). The absence of a specific time and place to grab onto in Your Attraction to Sharp Machines, as well as the interesting lack of actual, detailed physical description of anyone in the book (Is Elizabeth beautiful? Can you help but see her in big eyes and wild hair? ), also allows us to play with how close or far away some of our current culture’s beliefs might be from the book. Is there much of a difference between the way we look at female cyborgs and human females? When we are ‘creeped out’ by either of them, are our reactions similar? “This thing is not acting human enough for me.” When I hear the passion of Gregory Corso’s answer to the woman in the audience suddenly change, maybe unknowingly, and dribble down to that feeble indifference, (“Someday someone will write about them.”) I become a hollow pit. When I think of what Mahaney’s Elizabeth can’t tell me, despite all of the wonderful, lines and rich language that oscillate and swivel and burst around her, I become a hollow pit. Indifference, like the open mouthed shred between insanity and sanity, like the impossible play between the strange and the familiar that poetry crushes into absolute joy for me every day my blood moves, is innocuous right up until it’s not.

***

1 “I’m your dolly / stuffed with extra baggage” – “Go Home,” Lucius.

2 “The system was breaking down. The one who had wandered alone past so many happenings and events began to feel, backing up along the primal vein that led to his center, the beginning of a hiccup that would, if left to gather, explode the center to the extremities of life” (53, “The System,” Three Poems, John Ashbery).

3 “My name is Elizabeth / My life is shit and piss” – Elizabeth on the Bathroom Floor, The Eels

4 “But I ain’t so sho that ere a man has the right to say what is crazy and what ain’t. It’s like there was a fellow in every man that’s done a-past the sanity or the insanity, that watches the sane and the insane doings of that man with the same horror and the same astonishment.” -515, “Cash,” As I Lay Dying, William Faulkner

5 like Madame Psychosis / The Prettiest Girl of All Time / Joelle van Dyne in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest.

***

Carrie Lorig is the author of the chabooks NODS. (2013, Magic Helicopter Press) and Nancy and the Dutch (2013, NAP) with Nick Sturm. She is in the MFA program at the University of Minnesota and co-curates the Our Flow is Hard reading series.

Tags: Carrie Lorig, Matthew Mahaney, Your Attraction to Sharp Machines

i would have been in several asylums, and with no salad, that’s fr sure. thnx fr this carrie!

tinyurl.com/lr69xbu.

tinyurl.com/lr69xbu

v