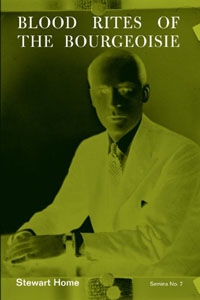

Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie

Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie

by Stewart Home

Book Works, 2010

120 pages / $19.99 Buy from Amazon

&

The New Poetics

by Mathew Timmons

Les Figues Press 2010

112 pages / $15.00 Buy from Les Figues

If you’re anything like me, you’re probably keen on the emergent discourse surrounding our current atemporal, altermodern new media status. Facebook, Flickr, Google, iPad, iPod, Myspace, Youtube, etc, etc: its all grist for contemporary philosophers, and writers too have attempted to capitalize on the ubiquity of Twitter feeds and Facebook updates – with mixed results. Zen literary terrorist Stewart Home and Los Angeles-based poet Mathew Timmons are both authors of recent books that are candidates for an emergent atemporal literature (for lack of a better term); what Home and Timmons have managed to do is to avoid the trap of the ever-expanding rotting mounds and heaps of aspiring internet-based fiction, and needless to say – that trap is the perennial lure of narrative storytelling.

It’s not so much that the urge to tell traditional narratives is dead or undesirable; it is more a question of convincingly reflecting registering the atemporal social reality in the developed world (presumably developing countries like South Sudan and North Korea are still telling themselves stories when they’re not dying of famine or scrambling for clean water). As futurist Bruce Sterling [1] puts it, practically no one immersed in our present new media network culture knows how to tell a proper “story.” The skill sets and the ideological impetus to even tell stories are simply not there. It’s just gone, Sterling tells us, and it isn’t coming back; to the degree that we have anything like a collective sense of progress or classical teleology – it’s been so ruptured by wiki-particles and hyperlinks, so shattered by search engines and BlackBerrys, so devoured by the global mass entertainment industry, that even the semblances to what was once a “story” are thoroughly unrecognizable as they are simply treated as “special effects” and juxtapositioned with other RPG fables from our pre-digital, pre-dial up modem past.

How, then, should we proceed from our current cultural impasse? Enter Stewart Home’s para-literary technique of recycling cyberwaste and appropriating penis enlargement spam emails by replacing generic references to women with the names of famous female artists. What?! Thus “Make Her Tremble With Pleasure!” becomes “Make Miriam Schapiro Tremble With Pleasure!” “Give Your Girlfriend the Best Orgasms Ever!” transforms into “Give Judy Chicago the Best Orgasms Ever!” Home’s book is rife with such examples, including an index listing abandoned porn quotes, and consequently Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie is one of the most idiosyncratic examples of how the internet and today’s resulting network culture is the purest exemplification of what Lacan called the lamella. Lacan, in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis describes it this way:

The lamella is something extra-flat, which moves like the amoeba. . . . But it goes everywhere. . . . it survives any division, and scissiparous intervention. . . . Well! This is not very reassuring. But suppose it comes and envelops your face while you are quietly asleep . . . I can’t see how we would not join battle with a being capable of these properties. But it would not be a very convenient battle. This lamella, this organ, whose characteristic is not to exist, but which is nevertheless an organ . . . is the libido, qua pure life instinct, that is to say, immortal life, irrepressible life, life that has need of no organ, simplified, indestructible life. It is precisely what is subtracted from the living being by virtue of the fact that it is subject to the cycle of sexed reproduction.

Of course, many authors before Stewart Home have successfully shown that the internet is “something extra-flat;” after all, the web is always experienced on flat monitors, flat screens, flat windows; even augmented reality is virtually always flat. And prior authors too have shown that network culture itself can go simultaneously “everywhere” and nowhere, and survive “any division, and scissiparous intervention”; for all practical intents the net is indeed an “irrepressible life” that has “need of no organ.” Home, however, complicates this lamella a step further by showing how social media itself is “precisely what is subtracted from the living being by virtue of the fact that it is subject to the cycle of sexed reproduction.” It is precisely against this background that Home’s art-infused penis enlargement adverts gains a certain charm and menace (no matter how you chop them up, they multiply and sprout back up like over-sexed zombie smurfs). An attempt to subtract and delete these one-liners from our increasingly amorphous data cloud would only prove Home’s point: consumer society stimulates in us envy and unrealizable desires that are intrinsically tied “to the cycle of sexed reproduction.”

Note the subtlety. The Lacan quote I previously excerpted is not claiming that the lamella is something totally alien and separate from human experience, quite the contrary. The lamella is intimately linked with the cycle of sexed reproduction; in other words, there is something in us – let’s call it our libidinal organ, that is “immortal” but is nevertheless grounded in the cycle of sexed reproduction. The paradox here though is that if we were to violently remove this inhuman alien amoeba, all it would do is make us less human – not more. Lacan further complicates the picture by suggesting we ought to nonetheless battle this terrifying being; after all, “suppose it comes and envelopes your face while you are quietly sleeping.”

How are we to oppose this super-libidinal lamella that is our new media environ that threatens to swallow everything and dissolve all identities? In The New Poetics Timmons opts to use a search engine and an algorithm as a kind of strainer or distiller to accumulate just exactly what is new in our new media. The final list that Timmons ends up with contains over 100 pages of “The New,” each packet of new-ness adding to our increasingly efficient communal prosthetic memory. Here is a short sample of the project (in alphabetic order): The New Criticism / The New Cultural Productivity / The New Culture / The New Dawn / The New Day / The New Deal / The New Death / The New Debility. Though a fair number of “The New” are without footnote, a chosen few are supplemented with edited text. For example, under The New Emotion:

The New Emotion is a collection of movement: Automatic Mechanical Self-Winding Movement. The key concept of The New Emotion is a multimodal presentation by a lifelike agent of emotion expression. The computing industry of the 1990s enabled significantly higher image quality, boosting diagnostic accuracy with less radiation exposure, giving us The New Emotion.

Like Home, Timmons is very keen on transcoding data from one medium to another, the rhizomatic subversion of postmodern culture by recycling and repurposing cybertrash. Paradoxically the overwhelming sense one gets from actually sitting down and reading The New Poetics is a sense of movement. Perhaps Timmons has serendipitously come up with something novel by terming The New Emotion as “Automatic Mechanical Self-Winding Movement,” his edited texts translate into a sensation of wandering geographies and neighboring psychogeographies.

It is important to note that one thought that absolutely did not occur to me as I was reading Blood Rites and New Poetics was: O, gee – why am I not reading this on a Kindle or an iPad? Admittedly, I have my share of tech-savvy friends who are genuinely mystified by my attachment to books, especially books that are published by non-mainstream arts-oriented groups like Book Works and Les Figues. The New Logic: Why pay money and wait on snailmail for these rotting, outdated, arcane, analog relics of the industrial past when I can just download it on my wireless broadband network for free? A few thoughts on this topic: Firstly, are we aware to what degree our ideas about technology are time-based? Forty years from now the iPad and Kindle will look about as arcane and obsolete as the Walkman or 8-track; already, my cousins are using their iPads as frisbees as they and my parents have grown bored of both it and the Wii. As for the frailty of the book as a technology – I own books that are 40 years old; my Kindle, on the other hand, because of a hard stop at a freeway on ramp, has been replaced.

To avoid any misunderstandings, I’m not arguing here that Blood Rites and New Poetics shouldn’t be open-sourced, perhaps they should; nor am I arguing that the book is somehow superior to new media. It’s just that having both projects as physical books recognizes a certain sensibility that history is more or less a literary project. And let’s face it: we’ve lost the thread of history. If modernity lasted from some time in the 1920s to the late 1960s and postmodernity lasted from the early 1970s to some time in the 1990s, our current atemporal state shouldn’t last for more than a few decades. We can call it post-postmodernity, altermodernity, the Electronic Baroque era, pre-Singularity, pre-post humanity – whatever we decide to call it, we can at least agree that it’s atemporal. We’re neither here nor there, neither at the end of history nor at the return of history. We appear to be stuck in a holding pattern, in just another transitional state – but a transition into what? From mayhem to chaos, and back again?

It is precisely in the face of such unfamiliar terrain that it helps to have certain books to reorient the disoriented. Isn’t this precisely how Timmons’ book functions? The New Poetics as an aid to organize and structure reality for us in a playful, albeit earnest, manner. Will The New Poetics prevent another 9/11 or financial meltdown? Will it mitigate another oil disaster or reverse global warming? Stop catastrophic earthquakes and subsequent tsunamis? Probably not. Nonetheless, Timmons’ efforts can help us sort of get our heads around the sheer massive-ness and messiness of it all; just the process of listing and juxtapositioning “The New” in alphabetic order has the power to reveal the quotidian in “The New.” The New Poetics certainly induces us to gain a sense of the intrinsic oldness in the new; after all, every future is someone else’s past, every past is someone else’s future. Whether or not the Singularity happens in the next 30 years or another 100 years, it will likely be helpful to keep a sense of perspective when confronted with the new. Dream as we might no one gets a clean slate.

Not to end this review on such a lugubrious note, it dawned on me as I was reading Blood Rites – with all the shit that’s recently hit the fan, let’s remind ourselves that we’re still living in a surprisingly exciting time in human history. For the longest time, History was a book that only the nation-state was actively writing, and the only literate institutions with the means of production to generate History were religious orders and states. Until very recently it was hardly strange to think of History as the metaphysical knowledge of the human race in its totality! How far we have come. Today practically anyone who has the means, motive, and opportunity can inhabit the role of a historian. For Stewart Home too, history is a minor history that can be in the unconventional form of an Appendix: Stewart Home Replies to an Enquiry from Guardian Newspaper Blogger Jane Perrone Concerning the Claim that he is the Real Author of the Belle de Jour Blog and Book. You see? Why not document your literary feuds & cultural activities and write an anti-novel like Stewart Home? – and, in the process, reveal MoMA’s Neoist Show for what it is: a false representation of the New made up of old post-Neoist material from the 1990s. Surprise! Surprise! It’s all a groove sensation! Grist for new media historians! Mister Trippy has once again tripped up the master narrative. Let’s join him! Everyone’s invited!

Tags: Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie, Book Works, Les Figues Press, Mathew Timmons, Maxi Kim, Stewart Home, The New Poetics

[…] Today is the launch day for our newly formatted reviews section at HTMLGiant, which you can see kicked off below with Maxi Kim’s review of Stewart Home & Matthew Timmons. […]

wow … what a stimulating article.

truly made me excited to be here, now. 2011.

My fave sentence from Timmons: “The New Motherfuckers has been cancelled.” His book made my Third Factory list this year. Again, Les Figues! Les Figues!

Well done. I understood about half, but that’s fine. As a kid I received a subscription to the New Yorker. It baffled me (the magazine). But I read and read (now 5, 10 years later) and started to understand 70, 80% of Nyorker, then eventually I felt I understood it all. I feel like you keep posting these type of things I will learn to come along. Thanks for it.

Funny, Mr. Leapsloth. Glad I’m not the only one. I grew up on Dylan Thomas and William Blake and Harper’s magazine. It took me years to get to meaning, though I loved the sounds and images and glimpses of understanding “something else.”

I’m deeply interested in the subject matter discussed above. I’m not sure I approach it at all in a similar way.

Lacan calls emphatic two-dimensionality (“something extra-flat”) the “libido”: an “organ” generative of “life” without-which-not but always already extruded by living beings – “subtracted” immediately by their “living” itself – due to its contrariety to death. –perhaps not “grounded in the cycle of sexed reproduction” so much as the or a condition for the possibility of that circularity.

(Well, okay, if the “libido” is the contextual constituent for “life”, then maybe it’s the or a condition for the possibility of anything at all. Maybe “libido” is a way of grasping that ‘something happens’.)

–but how is this “libido”, this “extra-flat”ness, more there in “the internet” than it is there in ‘Homer’? ‘Homer’ is a social medium – all media are social media – that is thoroughly hyperlinked. “Libido” seems to me to be “extra-flat” wherever language happens.

–and how is “the internet” or some part of it – a Twitter stream, say – actually “atemporal”?

These novelty claims: glamorous and glamorizing, and who doesn’t want to be glamorous?, but: what.

Much more people are on the net than on ‘Homer’ – network culture is

objectively more libidinal. Additionally, ‘Homer’ as a social medium

interfaces with a very small, generally academic and literate, clique.

The internet, on the other hand, is flat across six out of seven of the

world’s continents – always awake, never asleep.

For further clarification on the term “atemporal” atleast hear out the glamorous Bruce Sterling before you dismiss the term as mere novelty: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85joFsc1FSM

Here’s another great Bruce Sterling video on atemporality: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ne3ZFmzMOU4&feature=list_related&playnext=1&list=SPEBA42DF7953D8D87

And in response to deadgod’s claim that ‘Homer’ is hyperlinked – I see what your getting at. Yes, ‘Homer’ exists within a social context and yes, there’s alot of social references to a broader world in ‘Homer’ – but that doesn’t make it hyperlinked. What you get from ‘Homer’ and what you get from googling ‘Homer’ are two vastly different experiences; I wouldn’t claim that one experience is better than the other – but they’re simply not equivalent. It would be like comparing cars and horse drawn carriages, or manual typewriters and iBook laptops. You’re really comparing apples and oranges.

From – let’s roughly say – 900 to 650 BC, ‘Homer’ as a social medium included every Greek speaker in the most extra-flat, libidinal way. For several hundred subsequent (‘classical’ and ‘Hellenistic’) years of Greek-speaking civilization, ‘Homer’ as a social medium penetrated every literary and plastic artistic with a high degree of libidinosity. That historical horizon is what I was referring to with “‘Homer’ is a social medium[.]”; perhaps I should have resisted the temporally adventurous historical-present tense. So far, Facebook and Twitter are certainly not “objectively more libidinal” or extra-flat than was ‘Homer’ in the Homeric (later Iron Age) and post-Homeric Greek-speaking worlds.

By “novelty claims”, I did not mean that the claim of, for two examples, ‘atemporality’ and ‘the dissolution of all identities’ are themselves “novelt[ies]”; I meant that the claims for “the internet” are specifically novel in history – the history of claims made of social media – but generally not so uncommon: the claims of total human, social, or material change–claims of apocalypse. I think these claims mean to be, and sometimes are, glamorous.

In questioning, I dismissed nothing. I agree that dismissing something hardly encountered is a Badly Foolish Thing.

*artistic object

cross-posted (above)

I mean something ‘thicker’ by suggesting that ‘Homer’ is hyperlink-saturated (in a way that that connectivity is essential to the experience of ‘Homer’ in the worlds I’m thinking (fictively, yes) of).

To extend the metaphruit, I think that you’re comparing cars and carriages and saying that, now, we’re threatening to negate or abolish extension itself.

Let me watch those Sterling vids tonight; they’re a bit long.

I see your point – well-stated.

In terms of why our time is “atemporal” – as you’ll see from the Bruce Sterling video, his argument is not that our current historical period is timeless, or somehow eternally outside of time. His point is actually quite modest: unlike the prior Greek-speaking civilization, our English-speaking civilization doesn’t have a ‘Homer’ – in other words, we don’t share anything that resembles a common origin story; and we don’t have a firm teleology or shared narrative as to where we’re going, we as a civilization are more or less without a firm “cognitive mapping.” According to Sterling that’s why we’re in this weird atemporal state, and the internet isn’t really of much help in attempting to create stability in the narrative.

I wonder if you’d agree with him.

And to avoid any misunderstandings – atemporality isn’t necessarily a particularly good thing. From an atemporal perspective the Homeric world was arguably a better place; sure, they had their problems – but atleast they could kind of get their heads around it.

Of course, not everyone thinks we’re in an atemporal state. According to Zizek there are four grand ideological teleological narratives that people are still buying into (even with the chaotic ubiquity of the web): 1. Religious Fundamentalism, 2. New Age Spiritualism, 3. Technological Post-Humanism, 4. Secular Ecologism.

But I don’t know. As much as I like Zizek I think he’s wrong; the fact that we have four ‘Homers’ and that there are so many variations within each narrative – and so many cross-pollinations happening within these mutated teleologies only confirms in my mind that we really have lost the thread of history.

And I suppose the real reason I buy into Sterling’s argument is because I see it in my students; one student is into medievalist role-playing games, another is heavily invested in Mexican Catholicism, I have another student whose whole identity is mediated by riot grrrl albums from the early 90s, everyone’s just kind of in their own thread without an overarching grand narrative.

I do agree that Master Narrative is, today, fragmented into ninja-star kaleidoscopy – or that fragmented/fragmenting perspective stands, today, over against even the compelling mastery of this or that narrative.

For me, it’s not a matter so much of diverse identity packages, as with the, what, surfaces of your students. Rather, there are (at least) several narratives that reveal the organization of (or organize) each of those packages pretty well: inward disarticulation (Nietzsche), critique of political economy (Marx), dialectical entwinement of universal and particular (Aristotle), diversity of force constituting unity of substance (Spinoza), skepticism of skepticism (Kant), federal union (James Madison)–choose any one or any number of your own!

Is there a Theory of Everything that would illumine the unity and coherence of all successful Master Narratives (to the extent that each is successful)? — Not to my small mind.

Need no Master Narrative of master narratives be a destructive thing?

–and: still not sure what’s atemporal about all this competition to understand.

Maxi– wonderful review. Would love to get in touch as I’m currently going through ONE BREAK, A THOUSAND BLOWS and immensely enjoying it.