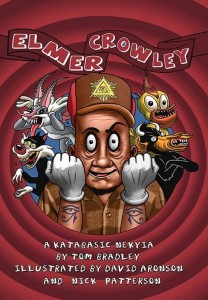

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia

by Tom Bradley

Illustrations by David Aronson and Nick Patterson

Mandrake of Oxford Press, 2014

134 pages / $14.99 Buy from Amazon or Mandrake of Oxford

Aleister Crowley is thinking about Germany’s late chancellor:

…my magickal child… who queefed out of my psychic vagina at an unguarded moment…[who] flopped from my left auditory meatus like a menstrual clot with incipient toothbrush mustache…

His mind wanders, logically enough, to Esoteric Hitlerism, the foetal religion presently aborning in Chile. He would like to drop by Santiago and have a chat, perhaps to “glean some intelligence from the gauchos.”

But it’s too late. No more time for the transoceanic jaunts that have varied his long life and kept boredom at bay. The Great Beast 666 happens to be on his death bed. Chapter One is over, and he dies.

Chapter Two begins as follows:

So, let’s sort this out, shall we?

In those seven words you have the essence of this particular historical figure: unkillable inquisitiveness, unshakable aplomb in the sort of psychic circumstances that drove so many of his apprentices and fellow magi insane. Of Crowley’s many fictionalizations, this novel gets best into his head. Erudite, prideful, lascivious, funniest man of his time, and the mightiest spiritual spelunker–he speaks and shouts from these pages as clearly as he did in his Autohagiography, which is paradoxical, given the irreal setting of Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia.

Now that his mortal coil has been shuffled off, Crowley doesn’t know quite what to expect. He has mastered the world’s ancient funerary texts as thoroughly as anyone who ever lived, but fundamental questions remain. Will he be privileged to climb the sevenfold heavens promised by the Gnostics? Will his eyes be offered a luminous series of Tibetan liminalities, clear and smoke-colored?

Apparently not.

Something else materializes and looms up, rather more architectural. It appears the Egyptians came closer than anyone to getting it right.

Crowley’s ghost has been deposited in the Hall of the Divine Kings, as described in the Nilotic Book of the Dead. Of course, our hubristic Baphomet assumes that he’s about to be greeted as a peer by the immortal gods, “the soles of whose sandals are higher than ten thousand obelisks stacked end-to-end.”

But, no, they brush him off like a midge. He’s expected to supplicate like any run-of-the-mill dead person, to have his demerit counterpoised in the balance against a feather. Godhood denied, our high adept has been doomed to reenter the tedious cycle of rebirth. Injured pride, disappointed expectations, the prospect of boredom–these have never sat well with Thelema’s Prophet-Seer-Revelator. He’s about to start behaving badly. (A signal for us to stand well back and shield our eyes and ears.)

If he must return to the rigmarole of existence, it will be on his own terms. Exercising his prerogative as a magus of the highest accomplishment, Aleister Crowley will pick and choose his next carcass. He cold-shoulders the Divine Kings and calls forth Baubo, the headless Greek comedienne-demoness. Her job is to whisper filthy jokes to the peregrinating monad, to get it into a “meaty mood” before it gets stuffed, yet again, among female intestines.

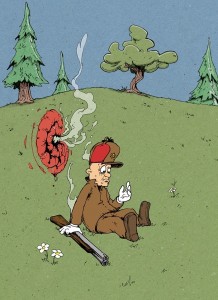

His fans and devotees will recall that Aleister Crowley’s speech was famously impedimented. Like a certain other bald, pudgy celebrity who will remain semi-nameless, he made his “R” sound like “W.” (A tied tongue is one of the natal indices of a buddha, as he proudly points out more than once.) Is it any wonder that a key phoneme of the magickal evocation should go mispronounced?

He accidentally summons a being who, in David Aronson’s accompanying illustration, looks familiar enough–but evidently not to Crowley. Considering himself to be laying eyes on the genuine Baubo for the first time, he enlists her embryogenetic assistance. Happy to cooperate, this pseudo-Baubo zips him into his new carcass (by no means the one he would have chosen) and sucks him into the inferno where he is doomed to wander for the rest of the pagination. At no point does Crowley realize the true identity of the Virgil he has conjured.

How is such misrecognition possible? In the life that just ended, didn’t our protagonist ever stumble, perhaps in a heroin stupor, through the door of a cinema in Soho, or Bombay, or Cairo, or New Orleans, and be subjected to an animated short subject featuring this baby-talking canary? How can we, the mere uninitiate, see what the great Seer can’t?

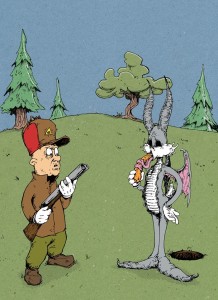

Think of all the things Aleister Crowley has ogled that would have scorched our exoteric orbits. In the Algerian Sahara he braved the Abyss and achieved full conversance with his Guardian Angel. In Egypt he personally received the evangel of the New Harpocratic Aeon in which we presently live and die. And yet, plopped like a newborn into Tom Bradley’s latest novel, the poor soul can only stare in unfocused puzzlement at his new self. He squints at the “series of obese white slugs writhing jointlessly on the ends of [his] arms.” Nick Patterson’s illustration, on the opposite page, plainly shows no slugs, but just funny fingers fitted out with the sort of white gloves that come standard issue in Looney Tunes Land.

It’s 1947, before the onset of television and Saturday morning kiddy-narcotizing hour. Cartoons are still made to be shown between feature movies in theaters, to audiences that include grownups. The art is done by hand, and full orchestral music is composed for each moment. In other words, the Mega Therion is sent into Merry Melodies Hell when it’s still worthy of receiving the magnificent likes of him.

It’s 1947, before the onset of television and Saturday morning kiddy-narcotizing hour. Cartoons are still made to be shown between feature movies in theaters, to audiences that include grownups. The art is done by hand, and full orchestral music is composed for each moment. In other words, the Mega Therion is sent into Merry Melodies Hell when it’s still worthy of receiving the magnificent likes of him.

As befits a neonate, Crowley’s senses don’t work well. For some chapters he must “proceed from a skewed seat of sensation” and “grope along with a tactility hardly worthy of the name.” But, thanks to the graphic perspicuity of Bradley’s illustrators, we the readers suffer no such handicap. As our ears listen to the protagonist narrating his myopic descent into the underworld, our eyes are privileged to enjoy a gnosis beyond his ken. We’re given a wordless wisdom unavailable to “the most gargantuan magus of post-Renaissance times.”

Here is revealed the fascinating and unprecedented relation of word to image in this book. Tom Bradley has long been known for repeatedly performing, at will, almost offhandedly, a task one would have thought impossible, perhaps magickal, in these latter jaded days: the invention of new genres. Andrei Codrescu hailed his quasi-nonfiction opus Fission Among the Fanatics as “the first appearance of a genre so strange we are turning away from naming it…” In the field of meta-scholarship, the late Carol Novack described his Epigonesia as “that rarity of rarities: a new genre, something like a superficially nonfictional Pale Fire, taking place in real time as the primary text alternately rides roughshod over, and is sapped and subverted by, the critical apparatus.” More recently, in his books Family Romance and We’ll See Who Seduces Whom, Bradley has yanked new kinks into the synaesthetic art of ekphrasis. He “accepted the challenge posed by stacks of preexisting art” and wrote a novel and an epic poem, respectively, around them.

Now he’s bulldozed into another new neighborhood. In Elmer Crowley, a katabasic nekyia, the artwork is given epistemological precedence over the text, which is deeply strange. Yet, even as that unique protocol is laid down for the first time in the history of book production, it breaches its own decorum. Ever deeper generic layers are exposed, like the grotesque frescoes of some Neronic bathhouse leering under a Vatican street crew’s jackhammer.

The Great Beast might not be able to puzzle out the exoteric designation of Looney Tunes Land, but he has no problem engaging the horrific anima that informs it. In his dysesthesia, forced to apprehend essences behind epiphenomena, Crowley shrewdly interprets everything in terms of the Egyptian and Tibetan Books of the Dead, the Greek Eleusinian mysteries, the Theravada school, Iamblichus’ brand of Neoplatonism, John Dee’s Enochian ceremonial, and all the other occultural traditions of which he is a past master. (Significantly, to his irritation, and eventual undoing, Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophy also keeps rearing its disapproving head.)

Accustomed to dealing with protean elementary wraiths and their camouflages, Crowley’s magickal mind sets about penetrating this world’s celluloid shell, intuiting the true demonic source of illumination behind it. And that intuition soaks straight into Nick Patterson and David Aronson’s pens, pigments and papers, to surprise our expectations when the next familiar character makes an entrance. Crowley describes a gray and white blur, with a—

…lascivious tuft of cottony fibers attached to what would, in the subphylum Vertebrata, be its sacroiliac… It seems to be mouthing a roughly penis-shaped item, some kind of vegetable, probably identifiable by its color. The visible spectrum’s mutilated in an indefinable way, so that I can’t commit myself as to it being a turnip or cucumber or eggplant…. A pair of roughly penile protuberances rise from the apex of what I assume, from its paramount position, to be the skull. I hesitate to call them horns, as neither seems particularly rigid.

But, steel yourself, turn the page and be enlightened. The scwewy wabbit who turned our childhoods’ Saturday mornings into orgies of giant sucking mouth-kisses and dynamite sticks down the trousers, has bat wings on his shoulders. Squid-tentacle suction cups encrust the inner surfaces of his ears. His eye sockets gape with the blackness of the bottomless pit. Crowley’s spiritual acuity has identified the chaotic grotesquery that, we only now realize, has always simmered under the technicolor surface of Leon Schlesinger’s cosmos. It turns out that Bugs is, and always has been, since his first appearance in 1940, none other than Choronzon. He’s the horrendous Keeper of the Abyss that comprises, of course, his “wabbit hole.”

And down into that hole the Great Beast 666 plunges. We follow him to the sub-basement of Hades, where “beasties and mutants of every unknown species are rehearsing a pageant, a loony Eleusinian anti-mystery.” Their formulary comprises the scatological doggerel he once dedicated to one of his more coprophagically inclined Scarlet Women. The Wickedest Man in the World turns out to be something of a prophet in these parts—

And down into that hole the Great Beast 666 plunges. We follow him to the sub-basement of Hades, where “beasties and mutants of every unknown species are rehearsing a pageant, a loony Eleusinian anti-mystery.” Their formulary comprises the scatological doggerel he once dedicated to one of his more coprophagically inclined Scarlet Women. The Wickedest Man in the World turns out to be something of a prophet in these parts—

All the miniature therianthropes and gryphons, the mutant beasties and mooncalves and woodland nematodes look up from their pious devotionals. They do a synchronized double take in the broadest Hollywood style, and throng me as if I were Christ running his skiff aground at Galilee’s water treatment facility. Asperging in all directions what passes for sex sauce, they wail in woe, they hymn in high ecstasy, they puff me up and empurple me like Pentheus in the Bacchantes.

“I tot I taw Aleister! I di-i-id, I did taw Aleister! Oooh, looky-looky everybody! Look who’s he-e-e-ere!”

Anyone who has found himself suddenly plunged into unknown surroundings (and who with any gumption hasn’t?) will instinctively try to make sense by recourse to past experience. Grasping for orientation, Crowley solicits the aid of a gallery of historical personages. Like Dante before him, he will see his contemporaries in Hell.

It’s only logical that Leon Schlesinger, creator of Looney Tunes, should be spending eternity in this abyss. In life, he, too, suffered from a speech impediment: the kind that sprays saliva with S-sounds. So, of course, he greets Crowley morphed into the person of Daffy Duck. Theodor Morell, Hitler’s personal Doktor Gutes Gefühl, who died at the same time as Crowley, is seen administering gigantic syringes of methamphetamine to all the little monsters. Due to a clerical error in the Divine Hall of Judgment, his soul has been stuffed into a hippo’s carcass.

As for Dr. Morell’s master, a.k.a. Crowley’s “magickal child—

Der Fuhrer and Emperor Hirohito are attempting to perform the expected soixante-neuf. But, though their salivary glands are cooperating, there is some difficulty. Symbolic retribution has burdened them with duck bills (though they could be platypuses as easily as mallards). Their matching toothbrush mustachios being extended far into space by these cartilaginous mouth parts, the former Axis leaders are hard pressed to achieve intimacy with what, upon scrutiny, proves to be this universe’s most horrifying and widespread characteristic: featureless crotches.

Porky Pig turns the generic tables, crosses the blood-brain-reality barrier, and makes a cameo appearance as the devil who, in real life, made steak tartare of Crowley’s pectorals at a Theosophical soiree in 1910. It’s an orgy scene full of unspeakable depravity and monstrosity, taken from Crowley’s own horror fiction.

Porky Pig turns the generic tables, crosses the blood-brain-reality barrier, and makes a cameo appearance as the devil who, in real life, made steak tartare of Crowley’s pectorals at a Theosophical soiree in 1910. It’s an orgy scene full of unspeakable depravity and monstrosity, taken from Crowley’s own horror fiction.

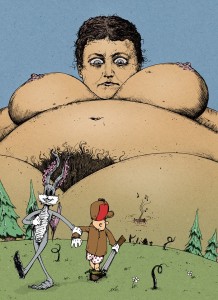

Meanwhile, a colossal nude Madame Blavatsky turns out to be the mountain upon which all this hellaciousness has been taking place–

And, speaking of Blavatsky, I won’t spoil the ending, except to say that the prophet of Crowleyanity comes to learn that the cosmos runs according to a Theosophical rather than Thelemic dispensation. The news is not good for practical occultists, because their spirits are doomed by Blavatskianity to be ground to sub-atoms on Kama-Loka’s adamantine floor. Under the astral grindstone, a sequel is rendered impossible, even in a genre that permits reincarnation–the ultimate sequel bait.

And, speaking of Blavatsky, I won’t spoil the ending, except to say that the prophet of Crowleyanity comes to learn that the cosmos runs according to a Theosophical rather than Thelemic dispensation. The news is not good for practical occultists, because their spirits are doomed by Blavatskianity to be ground to sub-atoms on Kama-Loka’s adamantine floor. Under the astral grindstone, a sequel is rendered impossible, even in a genre that permits reincarnation–the ultimate sequel bait.

The book ends affectingly with the man’s actual last words:

I’m perplexed.

Sometimes I hate myself.

***

Barry Katz is a wandering Jew from Jaffa, where, as a kid on a kibbutz, he picked green grapefruits.

Tags: Barry Katz, Elmer Crowley, Tom Bradley

A nekyia, νέκυια, is “a rite by which ghosts were called up and questioned” (LSJ).

A katabasis, κατάβασις, is a ‘going down, descent’, from the verb καταβαίνω, “to step down, go or come down” (LSJ). Physically ‘descending’ into a cavern to participate in (still-)secret rites was indeed the first part proper of being initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries of Demeter at Eleusis (the modern Elefsina, an industrial seaside suburb of Athens).

That last verb is also the first word of Plato’s Republic: Κατέβην […], “I went down yesterday to Peiraeus with Glaucon son of Ariston to worship the goddess, and at the same time […].”

Going down to worship a goddess (or god) makes a nice two-tongued pun.

Excellent point, deadgod. The double entendre is appropriate to the Mega Therion–though he doesn’t get much chance to go down in this book, because everyone is cursed with a “featureless crotch.”

Barbie and Ken… yikes. That’s some curse.

…actually, Bugs and Daffy. And Porky and Tweety,

Barbie and Ken/ Bugs and Daffy/ “featureless crotch”

reminds me of a joke i once heard

wanna hear a joke i once heard??

yes

amazing

thanks!

Q: what’s the last thing they give Tickle-Me Elmo before he leaves the toy factory?

A: two test tickles

And for self defense he’s issued a seam ripper.

The great Charlotte Rodgers, author of P is for Prostitute: a Modern Primer, has written a fine review of our katabasic nekyia:

“…this book is twisted, fantastical and genius. It captures the feel of Crowley with his bawdy, politically incorrect irreverence, his arrogance and his committed magickal spirituality and awareness…”

http://charlottejane2002.wordpress.com/2014/06/10/review-of-elmer-crowley-a-katabasic-nekyia-by-tom-bradley-illustrated-by-david-aronson-and-nick-patterson/

Now at the 73,000 hit-per-day Disinformation:

http://disinfo.com/2014/06/tom-bradleys-elmer-crowley/

In this excerpt poor Crowley receives a revelation of his public persona’s appalling future:

“They print my picture on the slip covers of their gramophone disks and vainly take my name in verses that could be scribbled on a privy wall in snot by a dog-faced demon. I, who poured my blood and breath into so many volumes of the greatest poetry the British Isles have ever produced, am being conjured, rousted from my eternal repose with little more than a chimpanzee’s mouth flatulence…”

(Is that Led Zeppelin in the illustration?)

http://antiquechildren.com/comics/tombradley.html

“…the author has a high knowledge of esoteric symbolism and Crowley’s works…Reading Elmer Crowley is like reading Crowley’s inner dialogue at 3am, after an intensive journey into his own inner abyss. It is therefore, a magickal working that Crowley himself would be proud of.”

Fine rave by Gwendolyn von Taunton in The Prometheus Review–

http://www.theprometheusreview.com/93-reasons-to-read-elmer-crowley.html

[…] –Barry Katz, HTMLGIANT […]

[…] —Barry Katz, HTMLGIANT […]