Pithy quotes about islands and humanity are plentiful and sift their way through our brains such that we are always aware of the metaphor of the island, fearful of our own loneliness and despair, careful of misstep, lest our desire for excitement and remembrance lead us to a fate like Robinson Crusoe. Wait: is Robinson Crusoe still in our consciousness? Or do you imagine, instead, a furry-faced Tom Hanks finding solace and friendship in a volleyball?

But islands do not have to be desolate. They can abound with exotic fruits and hammocks. They can be spaces for rejuvination and hope. They can promise hot romance, or something like that. It just depends on your conception of island. For most of us, popular culture tells us that islands – no matter how remote – offer nothing short of exotic and erotic adventure. Think: Gilligan. Think: Lost. Think: Survivor.

Judith Schalansky’s Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I have Never Set Foot on and Never Will inverts romance and the exotic into a concise and beautiful little book. By beautiful, I mean it is stunning and simple. It is an atlas, yes, of fifty islands: each one more obscure than the one before, many are mere strips of coral that rise above the ocean, still breathing, another is calcified bird shit, most are untenable, unlivable, barren save for ice or volcanic debris, others house thousands. This atlas should be considered a novel, or, at the very minimum, a collection of stories – the narratives Schalansky tells are more brilliant than fiction, if only because they are real.

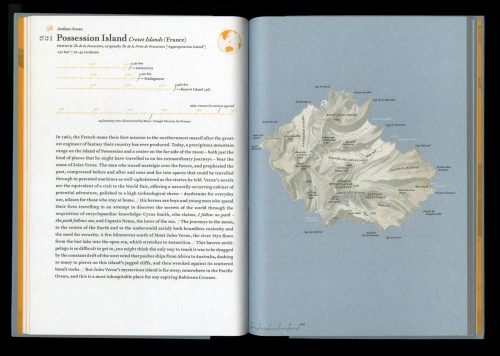

I’m not doing a very good job of describing the book though. Here is a sample page:

Each “chapter” is set up this way. On the left side, a description of the island: who “owns” it, distances to close landmarks, and a brief narrative about the island, whether it is a story of its inhabitants or its “discovery” or its vicious fauna. The right hand side offers an illustration of the island. It’s hard to say which part is more integral, probably because all these elements make this book what it is and the elimination (or addition) of just one piece would destroy the preciousness of this book.

My friend, Jeff Barbeau, lent me this book. Just for Geography Thursday. He is obsessed with Diego Garcia.

Me? I can’t stop thinking about Christmas Island. An island of a mere 135 square kilometers, Christmas Island has 1403 inhabitants. That’s not a big deal. What makes Christmas Island memorable is how roughly 120 million crabs converge on the island every November. They crawl out through the ground and make their way to the ocean to cast their spawn. The island becomes red. It is impossible to walk on a landscape of shifting crabs and their powerful pinchers.

It’s hard to say when the crazy ants appeared – what is certain is that a foreign traveler brought them – but by 1989, when the crabs made their annual trek to the ocean, this supercolony of yellow crazy ants emerged. Imagine 120 million red crabs. Imagine the number of ants it would take to eat through these crabs like acid. And not just like acid, no, they spray formic acid onto the crabs, which blind them, they lose their color, and within days, they are dead.

This is the story Schalansky relays. And I wonder: what about those 1403 inhabitants? Where do they go? Where can they hide? I imagine crabs and ants permeating walls, finding their way anywhere and everywhere.

So here’s a creative writing prompt: write me a story. Set it on Christmas Island. Who knows. Maybe some journal will make a special issue out of it. That’d be swell.

I may have written about Christmas Island for HTML Giant, but I’ve saved my favourite island for me, as my own writing project. It’s a secret, until it’s a book. Regardless of what my or your or anyone’s favourite island is, what is phenomenal about Schalansky’s book is that it has something for everyone. Inside this slim volume is an infinite muse. Why? Because it’s real. Because what is inside is more real than any imaginings can be, and that’s where it’s power resides. Had Schalansky written about 50 imaginary islands, it would be cool enough, sure, but because she composed an atlas of 50 real places, suspended in water, suspended in liquid space, places with real inhabitants and places really uninhabitable, I am left in awe, dreaming of these islands, some with barely enough land for my two small feet, others that house such lethal climates that my two small feet would dare not venture beyond this short reverie.

Tags: atlas of remote islands

: )

Also led to think here of Matthew Salesses’s Our Island of Epidemics, which does an amazing job of transforming one island into many by conferring this history upon it, abundance and loss alike, usually at once or in quick succession.

vipstores.net

loveshopping.us