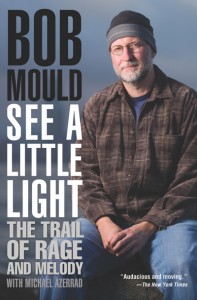

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

by Bob Mould with Michael Azerrad

Little, Brown and Company, June 2011

416 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

Why would anyone expect the ex-member of a famous rock band—those fertile dens of back-stabbing, girlfriend stealing, passive-aggressiveness and all around hurt feelings—to offer a healthy recounting of his time in said band? It’s like asking a combat veteran to empathize with the people who shot at him.

Yet, for those rock artists we truly admire, we crave that kind retelling. They’ve blown our minds so many times in the past with their transcendent work. If we’re disappointed they can’t deal with their issues enough to tell their band’s story in a fully-realized way, it’s only because we’ve learned to expect that much from them.

I skipped reading Bob Mould’s autobiography See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody (Little, Brown) after hearing Mould was less than resolved about his time in the formative post punk band Hüsker Dü, and in particular with his relationship with drummer/songwriter Grant Hart. I was a big Hüsker fan in the eighties and nineties, and I’d identified closely with Mould’s rage on classic albums like Flip Your Wig, Zen Arcade and Warehouse: Songs and Stories. I’d fallen away from his work around the time of his last album as the frontman of the band Sugar, and steadily found myself less interested in him as the years passed. The singer was so associated with the blood-curdling screams he’d let loose during his Hüsker years, I preferred to think of him as conquering his fury, moving on to better things, getting over it. Yet here was Mould, supposedly getting thorny about Hart and bassist Greg Norton in book form. Not interested.

But those who skip See a Little Light for these reasons will miss much of a story that few but Mould can tell: of Hüsker’s beginnings and ascendency, of the nascent eighties hardcore subculture in America that would lay the groundwork for the massive grunge movement in the nineties, not to mention refreshingly candid insights into Mould himself, one of his generation’s most conflicted icons.

Mould didn’t get riddled with rage by happenstance. His upbringing in rural upstate New York with an alcoholic, abusive father was plenty turbulent, and discovering his homosexuality in adolescence only further alienated him from those he grew up with. Most harrowing to me was when Mould was eighteen and for the first time away at college in St. Paul, Minnesota, trying to find his place in a confusing world. Not only were they stringing up homosexuals like deer back in his hometown, but, Mould writes, “the weekly phone calls with my family were difficult enough, especially the ones where my father threatened to sever my financial support or escalate his violence toward my mother.” I can only imagine a young, scared Mould desperately needing to make urban Minnesota work for him, knowing he had no home to go back to.

Luckily, he found barefoot drummer Grant Hart working at a record store, and with Grant’s friend Greg Norton the three formed a band that answered so many questions for the author. Mould fully embraced Hüsker, the perfect, frenetic container for his specific talents. He writes,

I could get anything done, maybe because I got myself so worked up about being the best. I had an incredible power of persuasion. If I got a thought in my head, I could make it happen—to a fault. I think that power came down to a mixture of testosterone, cheap speed, alcohol, and a lot of ambition. I could get people to change what they were thinking.

Such chemically-fueled ambition couldn’t last, and it wasn’t long before Mould’s need to control his band got the better of him. A telling point happens when, during the sessions leading up to the recording of New Day Rising, Mould vetoes one of Hart’s proposed songs, a first for the band. Mould writes, “At the time, I just wasn’t putting it together. I only meant to point out something. I think it really hurt him, and I think he viewed me as an adversary from then on.”

Still, Mould couldn’t loosen the reins, not only doing the brunt of the songwriting but also acting as band manager. He writes, “it wasn’t about needing to have power. I wanted to steer everything, but everything was Hüsker Dü and the fate of Hüsker Dü. It was taking what we had and making sure it was presented properly. I wanted the band to be as successful as possible, and every day I fought for that success.” No doubt Mould’s drive was a big reason for the band’s ascension, but it’s also not hard to imagine it being instrumental in its demise.

Moulddoesn’t quite make that connection in See a Little Light, leaving the impression he has yet to bring his story full circle within himself. Early lines about Mould’s adolescence like “I don’t think my drinking was a direct manifestation of misery. Despite the turbulent home life, I wasn’t a particularly unhappy kid” are clearly contradicted in later chapters. The Sugar chapters—where Mould takes the opportunity to show how much more commercially successful that band was compared to Hüsker Dü—often read like attempts to downplay his earlier band’s relevance. Mould mentions running into Hart and Norton once each during his Sugars days, and can’t resist attempting to make the other two look silly in the recounting. You can feel him detach from his narrative to prove his points, and the only point proven is that Mould hasn’t yet come to terms with all of it. Surely not a crime, but his story suffers.

We wonder what our role model’s next phase might be because we wonder what our next phases might be. We don’t want Mould to be angry anymore because we don’t want to be angry anymore. What a gift a fully realized memoir like See A Little Light would be to those who wish Bob only the best, and yearn for their own inner peace. In the end, like Hüsker Dü’s truncated career, this story burns to get there but doesn’t quite make it.

***

Art Edwards: Badge, the third installment in Art Edwards’s ten-rock-novel series, was a finalist in the Pacific Northwest Writers Association’s Literary Contest for 2011. His first novel, Stuck Outside of Phoenix, was made into a feature film. His shorter work has appeared in The Writer and Salon, among many others.

Tags: Bob Mould, See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody