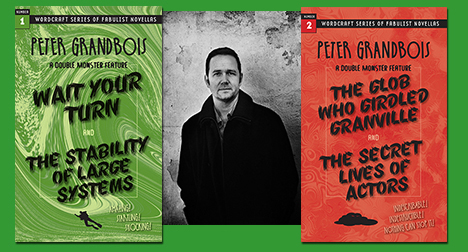

The Glob Who Girdled Grandville &

The Secret Lives of Actors

by Peter Grandbois

Wordcraft of Oregon, October 2014

There’s both a blessing and a persistent sense of cursed lack to ignorant reading, as when the reader has little or no foothold in the allusionary worlds that propel a given story, but, likewise, when the narrative doesn’t require any specific referential knowledge for engagement. Peter Grandbois’ “Double Monster Feature” of two, short novellas, The Glob Who Girdled Grandville and The Secret Lives of Actors, is such a collection, operating on a parodic platform while also completely rewriting this platform. Grandbois’ two main characters are B movie icons of the 50s—The Blob and The Thing—but rather than relegating these creatures to the shadowy sidelines, Grandbois explores them from the inside out, divulging their confusions, desires, and inchoate pathos. And even for those readers like myself, who are mostly unaware of the works’ cinematic histories, both stories unfold quite nicely on their own, doing so by cluing the reader via references to their filmic origins through tacky tropes and déjà vu moments of cliché, touching on our timeless and cheesy yearn for kitsch, for that passé sentimentality deeply ingrained in some collective pop-culture consciousness. Of course, and necessarily, Grandbois explodes these frameworks even as he builds upon them, breathing a new, complex literary life into both narratives, so that the thrill is one of uncanny insight and surprising tenderness.

A Rilke epigraph lifts the curtain on these features—“Oh, this is the animal that never was…,” which speaks to the troubled paradox of Grandbois’ project—humanizing the monster; as from The Glob:

Let us stand clear now and let the troubling story unfold, as we know it did from the newspaper accounts that came after. Of course, we don’t have all the details. We don’t need them. We know in our hearts what happened, what had to happen given the circumstances … Of course, even with our strong storyteller’s sense of empathy, we’ll never fully understand the mysterious life cycle of such a creature. All we really know is that he arrived here on a meteor, a mere babe of an amoeba fourteen short years before. His first experience of life one of hostility as that old man who discovered him poked him with a stick.

Grandbois’ two protagonists, as Rilke suggests, attempt to fashion the real through the unreal. Instead of letting his monsters remain ineffable, opaque, and struggling against nothing but impulse and base survival, Grandbois rescripts these creatures; even as their forms pervert physical paradigms, they are hyper-effable, all too finite, and this is their doomed struggle: the greatest monstrosity is being unable to grasp, only analytically mimic, human motivation and relationship. In The Secret Lives of Actors,

He walks out of the parking lot and down the street, unaware of where he’s going. Maybe she’s right, he thinks. Maybe I am the fraud. I’ll bet that bastard Hawks made me up for the movie. I’ll bet he invented the whole idea of a walking carrot … Who’s afraid of a giant vegetable, anyway? You can’t even love a vegetable because a vegetable can’t love … He wanders down Sycamore until he stumbles into the community garden … then he stops and sits among the carrots and green beans. “You’re right. I don’t belong here,” he whispers to himself. “I’m nothing but a Hollywood invention. Not even an interesting one. What would Nikki ever see in me, anyway? An actor who can’t feel. It’s like some sort of bad joke” … He spends the rest of the afternoon digging a hole for himself … Anything is better than this. This in between place. This place somewhere between life and death.

Both main characters lack nuance in form and content, but they are aware of this lack, as if any attempt at sincerity also surely destroys sincerity. And both main characters defy literary sense in laughable ways; they are as artificial as the “real worlds” they inhabit; however, to attempt to read them as metaphor produces no more answers than to take them within the logic of these worlds, for both creatures exist in the past and in the now, liminal animals of animated ekphrasis, contending with what it means to be aware of humanity, of memory, of some static history, while also pariahed, horrifically, from and by those temporal elements; The Glob:

Once safely back inside his new house, [he] barricades himself in the bathroom, takes off his disguise, and scrubs the area we might call his face. He stares into the mirror … He tries to remain fixed even as his body cocoons him. It is best we leave him like this for a month or so. The dark and violent churning of the soul is not a pretty sight. Look at him, now, collapsed upon the cold, tile floor. Something a glob would never willing do. Is that a fetal position he is curled into? It’s impossible to tell, but whatever it is, it’s unbecoming. Let us go. It’s the only decent thing to do, or so we tell ourselves. But you know the truth. You are starting to see through the veneer of our words already.

The first work, The Glob Who Girdled Grandville, does an excellent job preparing the reader (by blatantly incorporating the reader into the narrative) for the experience of the second work, because The Secret Lives of Actors—at least on initial impression—doesn’t seem to stand up to the narrative skill and poetic power of The Glob. Where The Glob is a haunting critique of domesticity and divorce—not the conventional manifestations of these states, but their ungraspable and inevitably reductive power—The Secret Lives of Actors reads as much less intricate, much more caricatured. Then again, if after The Glob infects you with its stylistic poise and surreal, introspective gymnastics, and you step away from its florid theater to meditate on its strangely touching absurdity, you’ll find a fresh take in Grandbois’ pursuit: exposing the underlying importance of the freakish clinquant that is our need for our own pop history. The Secret Lives of Actors seems to capitulate to some false formula of romance and tedious slapstick—there’s even an aggravation in the obviousness of the plot, to the plasticity of work’s entire emotional tone, but because the story comes on the heels of The Glob’s keenness, this allows the reader to cast eyes back on himself, his expectations, and the too easy tedium we have with our own sentimentality, even as it swells within us. Grandbois expertly weaves this metaphor of inescapable schmaltziness into the agency, or lack of agency, in his second main character, the original Thing. The fourth-wall awareness, the post-modern cynicism, our entire culture of actors and melodramatic emoting—this character, like the Glob before him, confront the reader’s cynicism by spotlighting our need for the B as some ballast to, or antidote for, our unbearable irony and all-too-certain savvy.

***

Nate Liederbach is the author of four books--Doing a Bit of Bleeding: Stories (Ghost Road Press), Negative Spaces: Stories (Elik Press), Tongues of Men and of Angels: Nonfictions Ataxia (forthcoming with sunnyoutside Press), and Beasts You’ll Never See: Stories (winner of the Noemi Book Prize for Innovative Fiction, and forthcoming in 2015). He lives in Eugene, OR. and Olympia, WA.

Tags: Peter Grandbois, The Glob Who Girdled Grandville, The Secret Lives of Actors