Pith & Amber

Pith & Amber

by Carah A. Naseem

Fugue State Press, 2011

102 pages / $12 Buy from Fugue State Press

Pith & Amber by Carah A. Naseem is full of texture and material, is performative, reaches language into the body of the reader. In response to the book, to the text, I will perform a reading in parts. First the outside of the book, its initial presence, its porous threshold. Next the first novella inside, scrape bark of the sycamore with your teeth; scrape the moon. Finally the second, longer novella, Cathay Umay. In all three movements: an attempt to meet with the book, to inhabit with the book the space of text, together to form a textbody, to allow the language of our textbody to scrape against my language and the language of Pith & Amber.

I. The Outside, the Initial Presence, the Porous Threshold

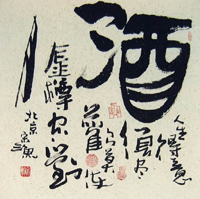

Handmade paper wrapped around the book. The skin of the book. The rough cut skin worn over the cover. The thick grain of its texture. Splinters in the skin, suspended in the skin. And the red obi around the skin. The paper and obi wrap, but do not contain, do not bind. When I look at the book, its skin is a thicket in which my eye is caught, my eye stuck full of the skin as it moves through to the image. The front image seen through the skin: blurred, dark shapes, symbols, writing, gathered around what almost looks like a face, two faces stitched together, the two faces of theater, and red blotches, blood drops, a mark left by a finger dipped in red. The back image seen through the skin: a dark landscape, an empty landscape, the smoke, the fog, the sky, the blurring of earth and sky.

I peel away the skin, hold just the skin in my hands, one side smooth, the other rough. I rub my hand over the rough side and one of the splinters in the grain sticks, clings to me for a moment, raises out of the book’s skin into mine. I smooth it back down. I wrap the skin around my face, look through it at my room, look through the thicket of grain at my room, blurred. Small holes in the skin. Gaps in the grain. I leave the skin on the desk, it moves when the wind blows through my windows.

The front image without the cover: the faces lose their face shape, collapse into symbols. A dark eye, a curve of nose all that remain. Characters from perhaps several languages gathered around the collapsed faces. No. Not written in several languages. Chinese calligraphy written in several hands. The red blotches, blood drips, intricately filled with white lines, lines scratched into the surface of red. Seals, red seals. Signatures. Five signatures on the image. The back image: the landscape, craggy and covered with thickets, and still the fog, the smoke.

II. scrape bark of the sycamore with your teeth; scrape the moon

From the beginning of the text I am set into propulsion, set into thick prose, set into the continual doing and undoing of repetition, set into the characters of speaker and “her” and “him,” set into becoming the landscape, the landscape of the body, the treebark scrapes against my tongue. A world created by her and him, through her and him. Through her and him a river unfolds: “He turns me into a river,” she says. Through her and him the rubbing of language, the blurring of bodies: “Before I was born, he had a face. When I was born I kissed his face, and he forgot his face.” Through her and him, creation: “Before I was born, the woods did not exist.”

A creation narrative. Or an accumulation of creative acts. An accumulation of narrative, knowledge, and truth woven and unwoven. Words become action, become material. The material gathered around bodies. “I did not know what it meant to kiss him. I circled around my tree and didn’t know about kissing. I kissed his face and he forgot his rib, he forgot his face.” The blurring of the face, the blurring of the body, the blurring of self: “His touch of himself touches into me.”

The speaker becomes the river, the river moves through the woods inhabited by the speaker, by her and him, inhabited by tree, the tree who is also the speaker, who is also the celesta, a soft bell sound. The river, the speaker resists the label of RIVER or TREE, wears a porous body, a body that grows into and plays host to landscape, unsettles ground, moves toward nonlanguage, unwriting, language scraped away, the speaker’s face covered with earth and mountain. What remains: paths, sources, breath, the “dark truth of earth,” electric fur. The synergy of earth and sky: “I am above and I am of the dirt.” The synergy of bodies and landscapes: “The river bursts forth from between my legs.” Later: “He unhinges his jaw, swallows the river.” What results: a birth, expansion.

III. Cathay Umay

Sun rises on Girl, and Girl in praise of the Name, hearing the Name in River in Sky. In reaching toward, looking for the Name, names pass through, those of Eje, Tengri, Niu, and Jianhai, but the characters ultimately become nameless—Girl, Boy, Woman, Man—become sound, songs through their bodies.

The chapters are short ritual enactments, performances (remember the “theater face” blurred on the front cover). Short braids of repetition and sound, and in the front of the text is the drum. The skin of language stretched taut over the drum, the drum hit, the sound of drum, and in that sound the world turns in so many ways. “Boy hits the drum. THE DRUM. The world flips upside down.” The skins of Girl and Boy, Woman and Man also drums. The skin wrapped around the book also a drum. In my ear the drum, in my throat the drum. The drum resounds, the world ready for birth.

Out of Earth and Sky, out of celestial milk, out of faces without bodies, out of bodies without brain stalks, out of sensory and knowledge deprivation come the birth, the re-birth of Boy and Girl, and between them the birth of story: “They kiss, cathay umay passes between their lips.” Their birth kills their parents, Earth and Sky removed, the names of Eje, Tengri, Nie, Jianhai removed, killed. In the final moments, I come back to the paper skin wrapped around the book. As this wrap suggests, the text wants the reader to wear the language as a skin. The skin prepares the reader. The story ends with “new ritual”: “Boy and Girl take the flesh of Eje and put it over their own before they step out into the world.” Eje’s skin is an earthskin. In the earthskin, Boy and Girl become names, die into Earth and Sky.

IV. The Skin Peeled: Words in Closing

As I read Pith & Amber, I thought of the myth, the ritual, the performance in the anthology Technicians of the Sacred, the body-as-landscape in Aase Berg’s With Deer, the electric fur of Bhanu Kapil’s Humanimal. Pith & Amber joins these as a text in which the reader feels the weight of words, their material presence in the body. The language builds and collapses, projects from the page, expands in the mouth of the reader, in the space of the reader. Like these other books, Pith & Amber scrapes me toward expansion, it projects beyond the page. Here in the text, “the world lacks boundaries that separate land from sky.”

***

A.T. Grant lives in Minneapolis. He has a band called New South Bear. You can hear them here: <http://newsouthbear.bandcamp.com>. He wants to play music or read poems in your house (or garage or at your boxing ring). His writing has recently appeared or is forthcoming in PANK, Sixth Finch, inter|rupture, and La Petite Zine.

Tags: A.T. Grant, Carah A. Naseem, Pith & Amber