Kanley Stubrick moves. It makes no sense and all the sense simultaneously, in the way it feels when something bad happens to you but you secretly feel like you deserved it. Or that feeling when all you wanted for breakfast was the giant banana pancake at Surrey’s Café in New Orleans on Magazine Street, but when you arrive they tell you they’re all out of the giant banana pancake batter so you get crushed and flippantly order the French toast and then it turns out the French toast is even better than the giant banana pancake but the catch is: it’s a seasonal thing and they won’t have it again for another year starting tomorrow. You know, so much of life simultaneously makes absolute sense and absolutely no sense at all.

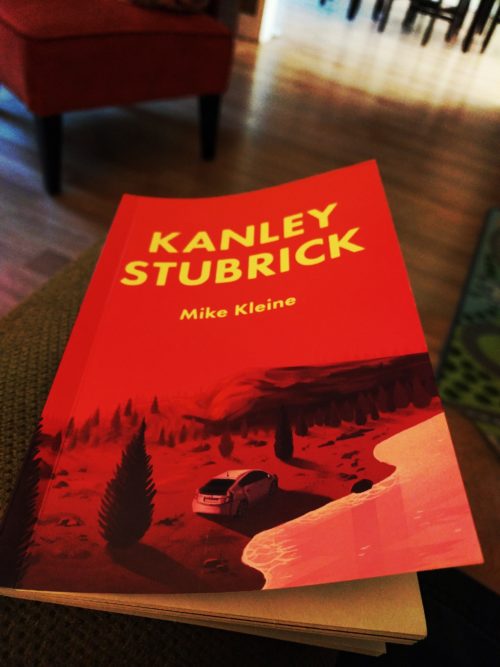

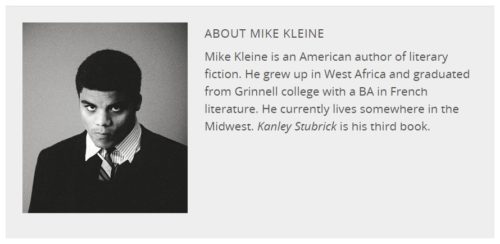

I’m sitting on our living room couch, late at night, the book sitting on the arm of the couch beside me. I’m nursing a head and chest cold of some kind. I think about the first time I heard about this book: last May I was driving We Heard You Like Books publisher Jarett Kobek up Laurel Canyon, over the mountains from Los Feliz to Northridge, because he kindly offered to visit my class to talk about his book ATTA, which I was teaching in a graduate seminar on the boundaries of the novel. He told me enough about Kanley Stubrick to intrigue my sensors. Now I’ve read it a couple times and I feel ready to write about it.

Kleine gives us plot, character, setting, and theme; however, each of those elements undergoes an estrangement. Plot on speed. Character on handmade animation realness. Setting on chopped up hyper-reality. Themes ranging from love, death, and travel. After a second full read and another flip through, I start to think about how it complicates the helpful binary pointed out by Gary Lutz (one of the greatest sentence writers writing sentences today) in his essential 2009 essay “The Sentence is a Lonely Place” published at The Believer, between the “page hugging” reader and the “page turning” reader. (In essence, the reader who lingers and scrutinizes at the sentence level compared to the reader who consumes at the larger narrative level.) Klein seems to have figured out an interesting way to push back against those categories. Through formal choices I will address, Klein finds a way to bring his sentences into unfamiliar territory while simultaneously moving the reader along rapidly. White space certainly plays an important part, but before I start heading down any specific rabbit holes, let me begin with the moment I realized this book classified as a keeper.

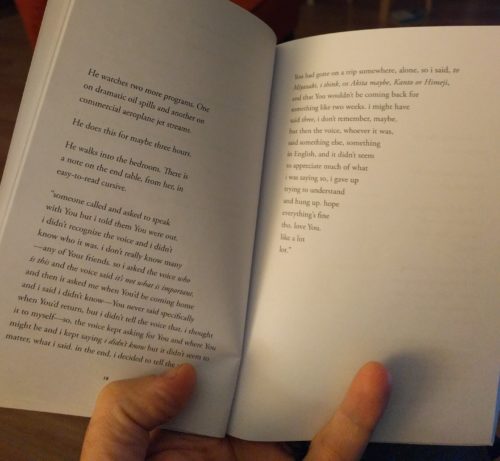

Maybe it’s 1:00 AM. The only light in the room comes from the little lamp on the table. I am in my family living room, sitting on the oversized orange chair we got at the World Market in Covington, Louisiana, when I realize Mike Kleine bookends this novel brilliantly, bringing the protagonist to a solid conclusion, or at least a solid turning point, by the end. Compare, for example, the opening, top of page 20, when Kleine writes:

He feels sick, like He

wants to die.

to page 102, the final page, the final lines of the book, SPOILER ALERT!, where Kleine writes:

Things get better.

And he feels like, I don’t want

to die anymore. But then thinks,

also, that’s a good thing too, I think.

From my perspective, it does more good than harm to reveal that arc, that connection, because a major joy of the novel comes from following the ever-changing and surprising journey of the protagonist. Watching how the main character gets from page 20 to page 102 makes the book worth reading, the facts themselves do little more than hold up the scaffolding of the wild and engrossing adventure. It’s that old saw about the value of the journey overshadowing the value of the arrival, wandering rather than purposefully seeking the destination, process over product, stop to sniff the roses, cherish the idler, the lounger, the Flâneur, that type of thing.

The protagonist—whose pronoun always retains a capitalization whether addressing Him as Him rather than him throughout, or when another character references Him by saying You as on page 23—amasses an incredible amount of experiences in search of his girlfriend who has disappeared.

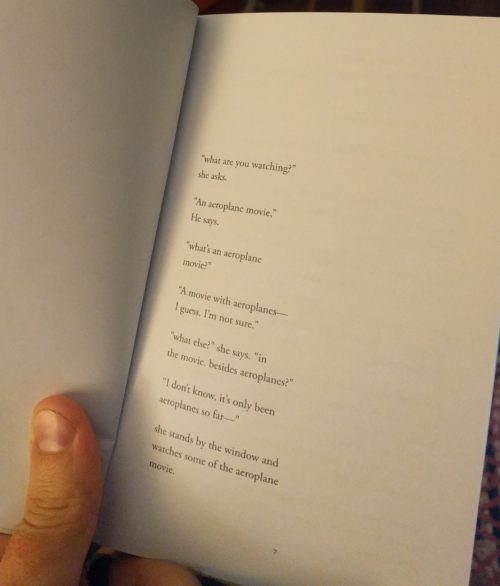

The first thing I do, I flip through the book to survey the page layout, get a sense of its general topography. All books I treat the same way. For some books, nothing comes from this practice: one page looks like every other page; but for other books it makes all the difference in the world. Kleine’s book solidly resides in the latter. When you flip through Kanley Stubrick something exciting happens. I got up from the orange chair and walked to the kitchen to find a snack, but brought the book with me. I’d told myself I’d go to bed earlier than normal, but here I am engrossed in this book, stuffing beef jerky in my mouth, and chasing it with limeade. The form becomes a pattern, takes shape, uses space in novel ways. As the entire novel sits left aligned with broken lines like a poem, the right side of the page plays a role in the whole thing:

Page nineteen, for example, when looked at from arm’s length, looks three quarters erased, smudged out like a clue, which plays into the mystery scenario unfolding in the text by echoing or intensifying the experience for the reader:

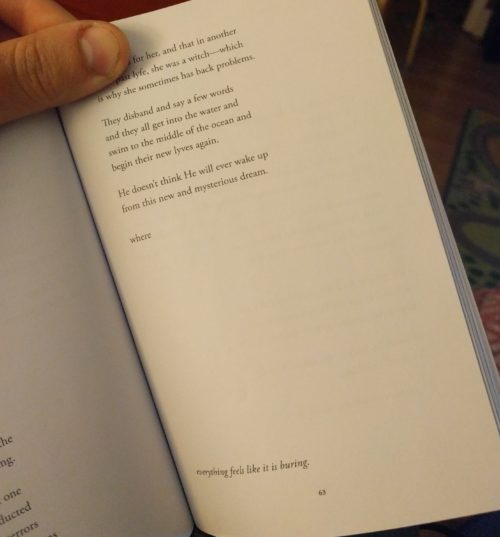

Page sixty-three when he admits to existing in a dream, and the words freefall causing a giant blank space between, “where…everything feels like it is burning.”:

More than once this book challenged me to define the term “novel.” How can a one hundred and two page poem-looking thing call itself a novel? E.G. Cunningham calls Kanley Stubrick “a novella-in-verse.” Maybe that’s the ticket?

Others will pick up the signals they pick up, since the text is a mirror, blah blah blah, but I definitely got a nod to campy surrealism, a nod to Murakami’s strangeness, the wonderment of Richard Brautigan, the creepy surrealism of Sony Labou Tansi, the Tao Lin deadpan tone or perhaps even more so the Bret Easton Ellis deadpan especially with all the product placement.

I read this book while listening to The Postal Service’s GIVE UP:

The movement on page thirty five, where Klein explains how the protagonist tries to kill himself in one stanza and in the next stanza changes his mind. On again, off again. Jump cut, jump cut, jump cut. Time dilates. A cult leader with an unpronounceable name. Japan. Peru. California. Bangkok. France. New York. Slam cut. Slam cut.

I finally finished the book enough times to sit down and write about it. This piece took a few days to write, over which a bunch of stuff happened making me realize life feels a lot like Kanley Stubrick, or perhaps certain moments in the narrative of this book echo reality in the sense that perhaps this too is all but a dream.

Probably ‘pataphysics would’ve been apropos to bring into this consideration.

Drugs, dreams.

I just checked Goodreads, and in response to a comment Kleine explains that Kanley Stubrick takes place within a shared world with his other novels. I’m intrigued.

Justin Goodman argues Kanley Stubrick shows us that “meaning can only be found by being seen and being in a scene.”

I didn’t say anything about the strange antiquated language and spelling.

Didn’t say anything about the Antonioni epigraph.

I am sitting on the couch in our living room, it’s 10:44PM. Here’s my favorite lines in the book, and then a video of Kleine reading from the book. Enjoy…

Next, He dials the Black Mountain

Institute and on the television, off-

screen, a beast tells the man in the

suit that at night, the other beasts,

they howl too, only because the sky

is made to look like meat. (pg.45)

PS – Heavens to Satan, it’s the resurrection of the unholy temple of HTMLGIANT!!! Glad to be back.

Tags: Kanley Stubrick, Mike Kleine, We Heard You Like Books

An example of the use of metathesis in which the first sounds of adjacent words are switched is called a Spoonerism.

“Novella-in-verse” is good, but why not ‘novella-length poem’? (The difference between prose and poetry, to me, is who or what determines the ends of the lines: if the writer, or the meter or other form chosen or accepted by the writer, decides the last words or punctuation marks in the lines, that’s ‘poetry’; if the last words or punctuation signs in lines are determined technologically (by the size of the characters relative to the surface they’re on), that’s ‘prose’.)