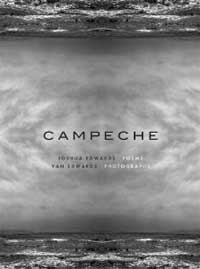

Campeche

Campeche

Poems by Joshua Edwards

Photographs by Van Edwards

Noemi Press, 2011

112 pages / $15 Buy from SPD

In the national artistic dialogue, there are usually but two coasts: East and West. The Gulf Coast barely enters the radar screen and, when it does, it’s normally because of a great tragedy like Katrina or the BP Horizon disaster. A chance for artists to express their solidarity or disgust or anger or sadness or pity.

So when I saw the description of Joshua Edwards recent book Campeche at Small Press Distribution – “titled after pirate Jean Lafitte’s name for Galveston Island, Campeche is a cautionary lyric composed of poems and photographs in which a real place is overlaid with the parable of a mythical world on the verge of an apocalyptic flood” – I knew I had to get a copy. Galveston reeks with history. History in this case being the more than 6,000 people who died on the island after a hurricane in 1900. Or history being the seawall or the fried seafood places and Salvadoran pupuserías all up and down Broadway. Or all of the dead trees from Hurricane Ike, tricked into drinking the salt water from the storm surge after surviving a long drought in 2008. And yes, it sometimes does get some winds from the North carrying down the smells of the oil refineries lining the Houston Ship Channel and Texas City, just up the Interstate.

More broadly, I’ve been obsessed for a long time with place: how anyone from their own small margin comes to speak to a larger world. When does place become no-place? When does a specific geography get to be universal? What kind of language allows particularity to escape provincialism? I was hoping Campeche would help me think about these questions.

I also knew I wanted to see the book because I think a lot about ways of combining image and text. I was interested to see what the poet, Joshua Edwards, and his father, photographer Van Edwards, had wrought. Well, in Campeche, the words and the photos produce a feeling that pervades the book: a brooding, syrupy aesthetic weighted down by both historical and impending loss. The photos locate the poetry in the alligators and roadkill, the boxy corner houses of Galveston’s avenues and the strange bird houses that mirror the larger homes for people. The sea, the sky, the trash brought in by storms and the wreckage left after strong winds. Everywhere there is evidence of nature and destruction. There are also people (of all colors), mainly looking like they walked out of the seventies or eighties (which sometimes leads to a certain nostalgia), at gun contests and always seemingly near the water, looking out at the sea or getting progressively more sunburned at the edge of the seawall. Or dancing in a swimsuit in the half-light of a honky-tonk.

We’re reminded these are real places made of sweat and sea and sand. Galveston Island becomes a kind of fading memory or a calamity-stricken ship at sail in perilously rising waters. The world created in the poems and the photos feels precarious, always already about to be submerged.

The first of seven sections is named for Deucalion, a figure from Greek mythology who survived a global flood unleashed by Zeus (much like Noah and the Christian God).

The “I” in this section is “hermetic” and his “blood is on fire” and he is “alone / in silence, which profiteers call sadness / but of course it’s not.” There’s a sense that the world is always impinging, at times violently, at times strangely and inexplicably. Edwards does the work of stating what I read as an ars poetica:

too serious, at others not serious enough,

I organize life with old ideas, in silence,

and with a cosmic sense of nature failing

I set off into southern wilderness to seek

some subtle center, as elusive as a crisp

dollar bill in the spillway of a penny arcade.

Nature is failing, the “I” is failing, the city and the island is failing. Things are looking bleak and the voice of the “I” is serious and seriously sad. But there is still a subtle sense of humor that somewhat alleviates the grim grayness, like at the end of the poem “Cold Green” when a subdued thinking about history and predecessors and a “bird too tired to fly” ends with the unexpected sentence: “It’s like repairing a foreign car.”

In this first section, the poems seem tight and contained, each one of them nineteen lines in length and paired with a photo. Each spread has a poem and a photo and the relationship between the two is never easy, never literal or illustrative. There is a relationship between the photos and the texts, but the relationship is like the one between consecutive lines in the book – often paratactical and slant.

The poems in the second section entitled “Campeche” seem to return to the idea of the ancient (or future?) flood moreso than the poems in “Deucalion,” despite its title. The poems dwell in tragedy, in the space of what might happen to the island of Galveston, to the Gulf Coast and to the speaker. In fact, if I read the poems as a kind of voice of the coast, the mournfulness of them seems less weighty, a bit lighter: “It is not pain that holds me back, but time / With its sad prefigurations and smell.” These poems are not afraid to be melancholy. Decline, perilous longevity and oblivion define the poems in this section: “All wine ends up as piss.” Nothing lasts, not even the land itself: “There will be nothing left here but the sea, / When it is done showing off its power.” The sea is rising, the carbon is floating “up in plumes,” and the poet is left on the island as the people flee, counting ships as they sail to the horizon.

A poem, “Seawall” in a later section, sketches out an ode to a seemingly cursed Galveston, pounded by hurricanes throughout its history ever since the 1900 storm I mentioned before (and which still holds the awful record as the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history). Throughout the 20th century, storms have threatened to wipe Galveston off the map, most recently in 2008. If not for the seawall built after the 1900 storm, Galveston would have sunk into the sea a hundred years ago.

Edwards writes an ode to the seawall, to its “protection / against the water’s teeth,” and in the process writes an ode to the island and the city:

Each storm describes it, and

Until the relentless

lives of fantasy and

will be known in this town.

But this small town is not just a small island or a small place (Jamaica Kinkaid dixit); rather, the island is a lot bigger: “The world could be bird or a snake, or an island someone left behind.” The book’s focus is a small island on the Gulf Coast and yet, this is clearly a book with grander ambitions. It’s a small island in an increasingly smaller world. As the same poem, “Seawall,” says, “I’d really like to speak to the world.”

Campeche clearly has literary ambitions. Its poems are well-crafted and often rely on traditional forms, like sonnets in its eponymous third section. I think this might be how this book answers my questions from before about place. It seems like the set structures, the attention to form and line, even the references to Greek mythology are an attempt to universalize or at least to locate the poetic concerns within a larger conversation. It’s an attempt to escape the margins. This approach isn’t my own, but I can learn something from Campeche: from its emotional rawness, its structured lines and stanzas, its commitment to old forms and, perhaps more than anything else, a son’s remixing of his own poetry with his father’s photos of an island they both clearly love.

***

John Pluecker is a writer, interpreter, translator and teacher. His work has been published by journals and magazines in the U.S. and Mexico, including the Rio Grande Review, Picnic, Third Text, Animal Shelter and Literal. He has published more than five books in translation from the Spanish, including essays by a leading Mexican feminist, short stories from Ciudad Juárez and a police detective novel. There are two chapbooks of his work, Routes into Texas (DIY, 2010) and Undone (Dusie Kollektiv, 2011). More at johnpluecker.blogspot.com.

Tags: campeche, John Edwards, John Pluecker, noemi press

mao lin

Lovely essay. Can you suggest other works that combine photos & poetry?

[…] among others. Edwards is the translator of María Baranda’s Ficticia and the author of Campeche (Noemi, 2011) and Imperial Nostalgias (Ugly Duckling, forthcoming). He is a lecturer at Stanford […]

I’m a BOI and but I don’t fully understand my gravitational pull to the water/wind swept island. I will read and relish words from a fellow lover of this place and hope to gain insight into my own deep draw to the gulf/bay shore that is Galveston Island, Texas.

[…] Edwards is the translator of María Baranda’s Ficticia and the author of Campeche (Noemi, 2011) and Imperial Nostalgias (Ugly Duckling, forthcoming). He is a […]