25 Points: Mad Girl’s Love Song

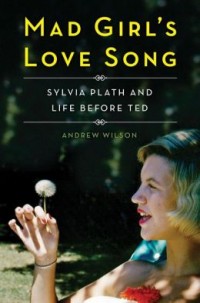

Mad Girl’s Love Song

Mad Girl’s Love Song

by Andrew Wilson

Scribner, 2013

369 pages / $30 buy from Amazon

1. After reading the Bell Jar and the biographical note in the back, the next piece of information about Sylvia Plath that I encountered was the only point of reference I had about her for a very long time. Alice Miller’s For Your Own Good features an essay called “Sylvia Plath: an Example of Forbidden Suffering,” in which Miller illustrates a scene of young Plath presenting to her mother and grandmother a pastel piece on which she has worked hard. The ebullience she demonstrates in showing off her achievement made a searing impression on me—I was not used to seeing female artists proud of their work; I was used to seeing them compromised and unfulfilled. The conclusion of the scene is equally powerful and so devastating, it remains my primary reference point regarding Plath as a depressed person: when her grandmother stood up, she smudged the pastel enough to ruin it. Plath’s flat affect, her inability to situate her disappointment where it belonged, has never not occurred to me when I’ve read about her, even though this scene does not recur with the canonical relish of, like, the St. Botolph’s Review launch party. By virtue of this scene’s inclusion in Andrew Wilson’s Mad Girl’s Love Song, I was swayed at first.

2. Plath’s writing is very important to me, and I love biographies where she is treated as the inexhaustible writer she was. As a subject, though, the way her work is so visceral, so loaded with the feelings that connect her to contemporary readers, that access overwhelming emotion, when she was remote, blank, totally affected: that I find riveting. Death notwithstanding, the more accessible her work, the less accessible she was. One cannot experience the closeness with her as a subject that one feels through her writing.

3. Although I bought and read the book because it’s about Plath, I am reluctant to use the biography as a means to discuss her because her work is more interesting than she is, so there’s that shame: why not talk about the work? In Wilson’s case, I do agree that the events of her young life are unfairly glossed over when she was so productive and disciplined so early, and for that I was excited to read Mad Girl’s Love Song.

4. The people in proximity to Plath aren’t ghosts here, either. Wilson talked to people who remembered her petulantly in some cases and fondly in others, and all vignettes get a greater sense of who they were than who she was, which makes for a livelier telling than what occurs from corralling facts from her archives—how real personalities generally unmoved by her achievements react to the young, raw person who remains animated in their pasts.

5. Her sexual voracity is emphasized as soon as possible, and much dwelled on are the rape fantasies she confessed to correspondent Eddie Cohen. The sole editorialization by the Wilson surrounding these incidents—which occur throughout the book—is: “We have to remember that Sylvia was a young woman overloaded with a huge store of sexual energy that she was not allowed to express…” This is pretty remarkable considering how Wilson handles other events.

6. Besides the unprecedentedly thorough examination of Plath’s childhood and Smith College years, the big news of this biography is how she demonstrated the tendency to self-harm in the immediate aftermath of her father’s death, and that self-harm manifested in the deliberately extreme and suicidal manner of attacks on the throat. This new fact, central to Mad Girl’s Love Song’s purpose, was the point at which I started to feel like I was reading Us Weekly not in terms of content but in terms of how I felt like, why am I reading this, I am so full of shame.

7. An aside: in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Laura Palmer knows she’s about to die. Agent Cooper points out how, while she did not commit suicide, she did consent to and prepare for her murder. In her last days, she warned her best friend, Donna, not to wear her stuff: don’t fetishize me, she was saying, don’t make me into a symbol or a set of aspirations, don’t channel me as a transcendent measure to get free from your boring suburban life; I am a broken person and I am in so much pain. It’s an incredible privilege that the dead girl gets – the audience is not only used to her as a structuring absence, but they’ve also seen Donna access her sexual awakening by wearing Laura’s sunglasses. Mad Girl’s Love Song is the kind of book Donna would have written about Laura Palmer: endowing talismanic power to incidents and items in lieu of presenting the facts of her life and why she is worth discussion.

8. “Although I thought [Plath] might be awfully good, I was on the cusp a little on how she might fit in. Her behavior was almost a performance, which I found a bit of a problem. You might be there another day and find an entirely different personality.” – Gigi Marion, college department, Mademoiselle

9. Eddie Cohen chastised Plath for her complete inability to be spontaneous, and the roots, extremes, and repercussions of her constant performance are explored fully in Mad Girl’s Love Song. Mademoiselle‘s ambivalence about Plath provides a great launching pad for a vital paragraph on the magazine’s own artificiality. The way the magazine fully constructed the “New York” experience that the co-ed guest editors has for too long gotten off without comment, but it is so much a part of what powers the Bell Jar, to wit, the conclusion may justifiably be drawn, it made a serious impact on Plath. It’s one thing to put on a face and look the sweetest and the most congenial, it’s another to play along with the mass hallucination that high-rise parties with hired dates have any place in reality.

10. “It was a lunch designed for the girls to get to know one another a little better, and we were at that stage where we were watching one another very carefully, all of us groping to see what we should do, how we should behave. Very shortly after we were seated—at this nice table with a white table-cloth—a large bowl of caviar was served. The caviar was supposed to be for everyone on the table, but Sylvia reached out for it, pulled it in front of her, and began eating. She proceeded to eat the whole bowlful of caviar with a spoon. I remember thinking to myself ‘how rude’…” – Ann Burnside Love, guest merchandise coordinator READ MORE >

April 2nd, 2013 / 2:23 pm