A Well-Lit Memory: Justin St. Germain’s Son of Gun

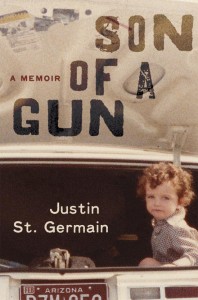

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

by Justin St. Germain

Random House, 2013

256 pages / $26 Buy from Amazon

As I read Justin St. Germain’s memoir Son of a Gun, I began circling all the times I came across the words “I wonder”: “I wonder why he never tried to call me, if he was ashamed, if he thought I was”; “I wonder where it is now, if she lost it, if I left it behind in the trailer”; “I wonder if she told him to say that, trying the same trick that worked on the judge who dismissed my case.”

The blurb on my copy’s back cover compares Son of a Gun to The Liar’s Club and This Boy’s Life, and while there’s certainly a likeness, St. Germain’s story isn’t so much as coming-to- age as it is remembering the moment he did—piecing together the events that led his step-father, Ray, to murder his mother with a shotgun.

At a cemetery, when St. Germain and some of his extended family fly to Philadelphia to bury Barbara, he mourns not the passing of his mother but the passing of his memory:

She fades a little more each day: I can’t picture her face, can’t remember a time when she was alive. I don’t know her story, because I’ve tried to forget, and because there was so much I never knew… Nearly a decade now since she died, and all that’s left of her are a few relics and my own suspect memories.

St. Germain opens, though, with perhaps the clearest memory he has: the afternoon he learned of the killing. Riding his bike home, he stares up at the expansive Arizona sky. It’s only been “nine days since the towers fell,” and he’s “newly conscious of planes.” When he arrives at his house, his brother, Josh, tells him the tragic news: “‘She got shot.’”

At a bar later that night, unsure of what to do next (“‘Wait, I guess’”), St. Germain drinks with his friends, watching President Bush address the nation on television: “He said that life would return to normal, that grief recedes with time and grace, but that we would always remember, that we’d carry memories of a face and a voice gone forever.”

Remembering “a face and a voice gone forever”—rounding out his “own suspect memories”—is what St. Germain hopes to solidify ten years later through his writing, and his struggle is not one of coming to terms with the tragedy (who can ever do that?) but of realizing that his recollections, his “truth” about his mother’s life, is what’s most important. That he starts with her death—that when he hears about what happened he doesn’t experience “shock” or “grief” but rather “a recognition, as if [he] had always known this moment would come”— presents an apparent contradiction: that one of his most vivid memories was formed even before it materialized.

Growing up in New Jersey, not far from Manhattan, most people I know can say what they had been doing on September 11th, while many also claim a counter-narrative, what they should have been doing, what they weren’t doing: they missed work because of a last minute disease; they didn’t get on one of the flights because of traffic; they decided not to take a day trip into New York that morning. I always thought there was a slight self-centeredness to such thinking—it could have been me, but wasn’t—and likewise, invoking such a large concept at the start, his mother’s death in the wake of 9/11, runs the risk of the same solipsism. St. Germain, however, does this so skillfully and so deftly that he’s completely changed my thinking, especially on the first matter. It’s not a selfish act for the could-have-been-victims of the terrorist attack to imagine if it had been them, or a loved one, or somebody they knew; instead, it’s a way to try and make sense of something insensible, even if it’s not completely shocking, or even, perhaps, if it’s already been there as a likelihood in one’s mind all along.

June 16th, 2014 / 4:30 pm