Murder: An Interview with Nathanaël, Translator of Danielle Collobert

Forthcoming from Litmus Press this April, Nathanaël’s definitive English translation of Danielle Collobert’s Murder marks the first ever of this French poet’s debut book. Originally begun in 1960 when Collobert was twenty years old, and published by Gallimard in 1964 under the auspices of Oulipo-founder, Raymond Queneau, this book laid the groundwork for what remains one of the most enigmatic and innovative bodies of work in contemporary French letters. As with the subsequent works of Collobert’s brief but impactful output, which lasted until her suicide in 1978, Murder speaks a language profoundly its own, unlike anything else she was to write, and quite possibly unlike anything else you may have read. Reading this prose gives one the rare impression of being in the presence of a voice speaking from the honest and cutting edge of present urgencies: that is, this is not a voice responding to conventions or trends in literary necessity, but one singularly engaging the emergent necessities of life itself, in all its complexity and danger. Here, in honor of Danielle Collobert and this fantastic new translation, Nathanaël and I discuss her life and legacy with an eye on her first work, Murder.

***

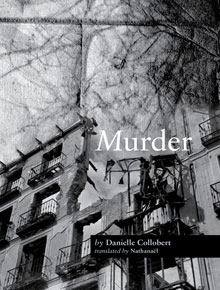

Murder

Murder

by Danielle Collobert / translated by Nathanaël

Litmus Press, April 2013

104 pages / $18 Buy from Litmus Press or SPD

Kit Schluter: To begin, what drew you to Danielle Collobert’s work? How did you discover it?

Nathanaël: I want to say that it was accidental, but I’m quite sure it wasn’t. Unless one understands friendship as accident. I entered, as did many, into Il donc, and Collobert’s Carnets, though with an eye turned away – perhaps out of a desire not to seek the life in the work, however much it is written there, and with such determinacy; the ‘twenty years of writing’ set against the impending suicide. Still, it is a hazard of hindsight to be able to set the life against the work, though this is so obviously a deformation of the reader, and so I resist as much as I can the tidy narrative of a life fallen from letters. The short answer to your first question is: Collobert’s language. But if the virtuosic remnants of Il donc are almost a perfect epitaph to the twenty years, I was much more viscerally and immediately impelled by Meurtre; I even borrowed an epigraph from this work into We Press Ourlseves Plainly much before the idea even of translating it had presented itself to me. Perhaps most immediately because of a shared concern, or conviction, that the distinction between murder and death is unconvincing and too readily upheld.

KS: What were the circumstances surrounding Danielle Collobert while she was composing Murder? Do you find that the book draws material or imagery from her experience?

N: My knowledge of Collobert’s biography is quite limited. Not unlike her parents and her aunt, who were all actively engaged in the Résistance during WWII, Collobert, a supporter of Algerian independence, was a member of the FLN (Algeria’s Front de libération national) at the time of Meurtre. She chose exile in Italy, where she completed work on the manuscript. It may be worth underscoring the importance of 1961, for the outcome of the war, which, in French contemporary society was never acknowledged under the name of anything other than the euphemistic “les évènements” (“the events” – to do otherwise would have been, not only to have acknowledged, if only semantically, Algeria’s nationhood, but the repressive force employed by France to resist – and as it happened, to defer – decolonization and independence). On October 17, 1961, a peaceful demonstration of many thousands of Algerians living in Paris, protesting the curfew imposed exclusively upon them, and the acts of police violence to which they were systematically subjected, was violently suppressed by Vichyist Maurice Papon’s police force, resulting in the arbitrary deportation of large numbers of Algerian demonstrators, and the summary execution of up to two hundred Algerians, many of whose bodies were pulled out of the Seine in the following days; several thousand Algerians were rounded up during the demonstration and distributed among prisons, the Palais des Sports and area hospitals. Several months later, on February 8th, 1962, what has come to be known as the Charonne Massacre took place at the eponymous Paris métro station; this demonstration, organized by the Left against the paramilitary OAS (the reactionary Organisation de l’armée secrète, which violently opposed Algerian independence), and often conflated in people’s memories (and in historical accounts) with the October massacre, resulted in the death of eight demonstrators at the Charonne métro station. It is not insignificant that French FLN supporter Jacques Panijel’s 1961 film, Octobre à Paris, which documents the moments before, during, and after the October demonstration, was censured by the French government and only shown for the first time in a French cinema in 2011 – half a century after it was made.

The photograph on the cover of Murder accounts, obliquely, and somewhat prochronistically, for these activities – it is a photograph of a bombed out building in Madrid, taken in 1937 by Robert Capa, during the Spanish Civil War.

Meurtre is tempered by the residues of such histories; but the work’s strength is in its ability to evoke them without resorting to explicit accounts, or naming. The generalization of historical violence is embedded in the intimate accounts presented to the reader – seemingly placeless, nameless, they nonetheless achieve historical exactitude through relentless repetition – a reiterative (mass) murder (one is tempted to say: execution), which afflicts and incriminates the gutted bodies that move painstakingly through these densely succinct pages.

25 Points: The Book of Monelle

The Book of Monelle

The Book of Monelle

by Marcel Schwob

translated by Kit Schluter

Wakefield Press, 2012

136 pages / $12.95 buy from Wakefield Press or Amazon

1. Let’s just start with the fact that this book made me cry. It’s an utterly heartbreaking book, beautiful in the torment and suffering that is manifested through its words. Though Monelle instructs, “Words are words while they are spoken. / Unspoken words are dead and beget the plague. / Listen to my spoken words, and act not according to the words I write,” these written words are the only spectral trace we have left of her.

2. I first heard about the new translation of this significant work at Harriet.

3. The synopsis of the book reads: When Marcel Schwob published The Book of Monelle in French in 1894, it immediately became the unofficial bible of the French symbolist movement, admired by such contemporaries as Stephane Mallarmé, Alfred Jarry, and André Gide. A carefully woven assemblage of legends, aphorisms, fairy tales, and nihilistic philosophy, it remains a deeply enigmatic and haunting work over a century later, a gathering of literary and personal ruins written in a style that evokes both the Brothers Grimm and Friedrich Nietzsche. The Book of Monelle was the fruit of Schwob’s intense emotional suffering over the loss of his love, a “girl of the streets” named Louise, whom he had befriended in 1891 and who succumbed to tuberculosis two years later. Transforming her into Monelle, the innocent prophet of destruction, Schwob tells the stories of her various sisters: girls succumbing to disillusion, caught between the misleading world of childlike fantasy and the bitter world of reality. This new translation reintroduces a true fin-de-siècle masterpiece into English.

4. The Book of Monelle is a book of words, like the Bible, these words may transcend its physical pages. In its biblical and prophetic tone, Monelle, perhaps herself a prophet, speaks of the beginning: “And Monelle said again: I shall speak to you of young prostitutes, and you shall know the beginning.”

5. If Monelle is a prophet, she is utterly of the present, of the moment, and of silence, because in life and suffering everything becomes a mirror to one’s suffering, and because in death there is only silence, but there is also the hope of forgetting.

6. Monelle instructs: “Do not remember, and do not predict.”

7. The translator gives two possible ways to interpret the name Monelle. First, the French translation that roughly translates into “My-her,” which implicates a strange hope for possession. Indeed, the narrator (whom we take to be Marcel’s tortured self) says, “And as I looked over the plain, I saw the sisters of Monelle rising.” Because every “her” is Monelle. And Monelle is every her. And yet, Monelle is of the past and infinitely elusive.

8. Monelle, its prefix derived from monos, then also implies a numeric singularity. Monelle is now and always alone. Schluter, in a footnote to his afterword, describes, “The infinite solitude that draws the narrator toward her is the very force that must ultimately repel him. In the end, no matter how we attempt to grasp her character, her name should be the first clue that Monelle will fade into abstraction in the fashion of a mirage or a dream recalled upon waking.”

9. Monelle speaks: “…for it is necessary that you lose me before you find me again. And if you find me again, I shall elude you once more. / For I am she who is alone.”

10. And then: “Because I am alone, you shall give me the name Monelle. But you shall imagine that I have every other name.” (Louise, Louvette, Lilly, Bargette…) READ MORE >

November 7th, 2012 / 1:01 pm