25 Points: Journey to the End of the Night

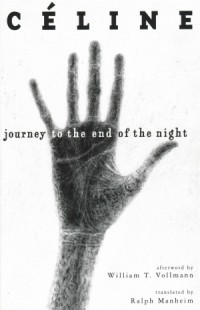

Journey to the End of the Night

Journey to the End of the Night

by Louis-Ferdinand Céline

New Directions, 2006

464 pages / $17.95 buy from New Directions

1. Will Self compared Joyce’s life before Ulysses to Céline’s experience in the war before writing Journey, in his exquisite discussion of the book upon some anniversary publication in The New York Times. I think I read that review about halfway through the novel and it complimented the thing quite well, gave a necessary contemporary slant on the whole thing.

2. Though remembered—much like Knut Hamsun—for his anti-Semitism (later in life) before his talents as an author after so many years gone by, a return to Céline and this novel in particular has occurred among authors and intellectuals almost every decade since its publication in 1932.

3. A new sort of manic transcription of the author’s experiences through his protagonist Ferdinand Bardamu jettisons the reader from war-torn France into the jungles of colonial Africa (my absolute favorite portion of any picaresque I’ve ever read) to post WWI America and back to France without missing a beat and yet the effect is akin to a hammer pounding against your chest.

4. I’ve read the book on three occasions, the last of which I suppose I felt ready enough and barreled through it in a couple of days and felt the aforementioned chest pounding that I’ve never experienced reading another book.

5. Its second translator, Ralph Manheim, also translated Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

6. Every time I remember that this is Céline’s first novel a little part of me that used to believe in writing as a career dies, then runs itself over in some hellish ghost tank, and dies again.

7. Famous for his use of three dots (“…”) in the sprawling paragraphs of his books, Céline—to me—has created a new and perfectly original way of de-Salinger-izing your first bildungsroman and turning it into a strange fucked up masterpiece.

8. Here we have the antihero, and the antihero’s doppelganger (in so many words) Robinson, who comes out of nowhere after any number of times to keep the protagonist company while he evades work, wanders around like a lunatic, and speculates about the desperate stupidity of mankind.

9. Bardamu’s a fan of kids, however; this being one of the few hopeful characteristics of the man. He believes in them, the promise of a good future, that maybe—just maybe—they won’t wind up shit like every adult he sees around.

10. The simplest characterization of this book is to say that it’s a picaresque, which is valid, but feels like the largest slight inflicted upon a great work of literature since everyone said all that shit that one time about your favorite whoever the hell; so I don’t want to do that. I want to call it a bible for people with less-than-hope but more-than-pettiness who hope to suck the congealed blood from the wounds of a better life forgone in the name of money, or democracy, or the nuclear family; and those who read it needing that companionship, needing that sense that all is not lost just yet, you’ll find it here. READ MORE >

November 1st, 2012 / 12:09 pm