25 Points: The Emily Dickinson Reader

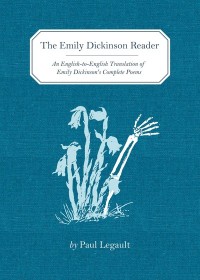

The Emily Dickinson Reader: An English-to-English Translation of Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

The Emily Dickinson Reader: An English-to-English Translation of Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

by Paul Legault

McSweeney’s, 2012

247 pages / $17.00 buy from McSweeney’s

[Note: In the text that follows, the leading number refers to the catalog number assigned to each Dickinson poem and its accompanying translation. These numbers are derived from the Franklin (1999) edition of Dickinson’s oeuvre. The trailing trailing number appearing in square brackets references the actual “point number”, and thus the in order in which the reviewer would prefer, although would not require, that these 25 points be read. JM]

12. Concurrent with my reading of Legualt, I’ve been following Brandon Brown @ Harriet (the blog) on translation. How he says, “There is no master.” I feels it applies here, too. But maybe Brown and Legault are colleagues, correspondents, even. (One of them, surely, is wren-like and sherry-eyed.) Or the inventions are independent identicals, like Darwin and that other guy*. I imagine Brown and Legault meeting in some profile coastal city with a very specifically desirably demographic profile, dotted with saloons and taverns, meeting over craft beers intensely hoppy and a shared literary ambivalence which tastes of salt without being salty per se. But this meeting, which is like a prelude to a deeper or longer encounter, this meeting wordless, sudsy… these beers, these refreshments bitter and compulsory… the possibility of Brown and Legault merely overlapping at the bar is as far as my imagination goes. And is this stopping heartful, braked by the anxiety of influence? “Emily Dickinson wrote in a language all her own, thus the need for this English version of what she meant.” (7) Wait, so does the agony of influence deny the mortification of the flesh? [3]

29. Handed over to the hand that writes, “simple” and “direct” are always driven forward. I mean, forward as out or away, into that exile that enable observation, not into the completed future of conveyance. (That, and I just don’t trust McSweeney’s.) [4]

98. Biography bugs me most of all. I wish we had no daguerrotypes of Dickinson to caption. I wish reading really pressed some sort of pause button on life itself. I wish I didn’t feel like I, too, know how caretaking will warp you. [16]

167. But with such rueful wishing, if not in it, a realization disappoints me with surprise and surprises me with disappointment: I have this idea all the time. [25]

221. Translation isn’t telling, much less re-telling. But it snags in the same temporal flow as does narrative. [7]

319. What was Dickinson herself translating? Emerson? Swedenborg? Whiteness: “racial,” temperamental, existential (not a word she would have recognized, not for all the tenements in Amherst)? The Puritanism that idles with such delightful perversity in Frost’s “The Generations of Men”? The erotics of a universal chlorosis? Proverbs she found when she dreamed of communion in the hills so misty from her gnomic lookout? Hell, that’s it. Dickinson, even her doubts are too bold. For all Legault’s contemporary light shines, it can’t cast her shadows. [8]

333. Not that I think Dickinson’s—or any poet’s poetry, for that matter—is inviolable. Reading it will always rough it up anyway. But what about introversion? [2]

392. Consider Paul Legault’s project a sort-of ekphrasis on Dickinson’s unwritten autobiography. Consider that Dickinson’s medium isn’t poetry, that Legault’s isn’t comedy (though more than a few of these read as if they could have been spouted by a vintage, arrow-through-the-head Steve Martin), that there is no translation evident here, only notation, only commentary, only adumbration, thoughts broken in the process of their own manufacture by the machine that is, quite literally is, addiction to the author’s held-out promise of exegesis. Consider your prurient self covertly mocked. [21]

421. Emily Dickinson isn’t your friend, and never was. Anyway, friendship thrives on novels (its parasitic), not poems. And Emily Dickinson does care, in the sense that she wants to know something true of her own being. That she would exemplar herself, if only privately. [20]

438. The apostrophe of the second-guess. The syntax of the spit-take. After all, the literal is the absurd. [13] READ MORE >

January 3rd, 2013 / 12:09 pm